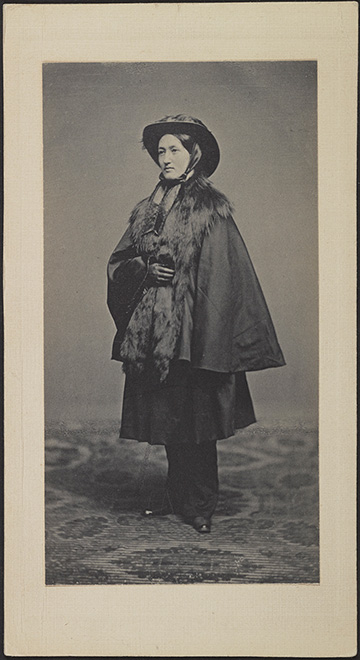

These American pre Civil War clothes for women were designed in such a way that a woman’s waist, constricted by a whalebone corset, was responsible for supporting the weight of as many as 15 pounds of 6-8 starched petticoats stiffened with straw or horsehair sewn into the hems and voluminous skirts. Dress reform was a significant focus of concern among early women’s rights activists and for good reason. A “wasp waist,” created by tight lacing of the corset, restricted deep breathing, worsening pneumonia and tuberculosis, diseases that afflicted huge swaths of the population in a pre antibiotic age and resulting in premature death. Women’s back and pectoral muscles grew dependent upon the support of the corset and atrophied. Skirts dragged the ground, collecting filth. Women—styling their hair, changing clothes throughout the day for different events, keeping up with the latest trends from Paris and Germany, sitting for dress-fittings—spent an inordinate amount of time keeping up appearances in heavy clothes that allowed neither free movement, decent digestion, nor comfort. 1858

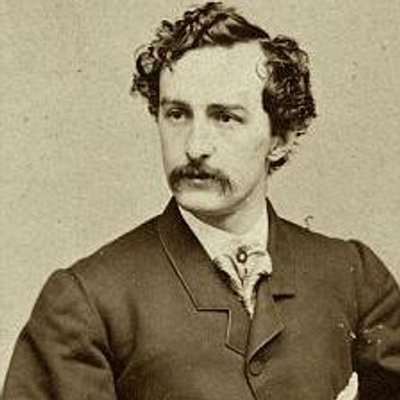

Amelia Bloomer

In early 1851, Amelia Jenks Bloomer (1818-1894), the first American woman to own and operate a newspaper (The Lily), took up the idea of wearing a short skirt and loose trousers gathered around the ankles. It was a notion popularized by her friend, Elizabeth “Libby” Smith Miller, who felt that long dresses were “heavy and exasperating.” Amelia made this fashion switch when Libby came to Seneca Falls, New York to visit her cousin, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who was Bloomer’s neighbor. 1

All three women used their voices to enact social change, particularly in the areas of women’s rights to better education, better pay, wider fields of employment, the right to vote, and dress reform. Soon these pioneer feminists were appearing on the village streets wearing their sensible and comfortable short skirts and full Turkish trousers.

Elizabeth Smith Miller (1822–1911), photographed wearing her bloomer outfit, 1851. Carrie Chapman Catt Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (011.00.00)

Amelia Bloomer announced to her readers in The Lily that she had adopted this new dress. In response to many inquiries, she printed a description of her dress and instructions on how to make it. Bloomer recalls the response:

At the outset, I had no idea of fully adopting the style; no thought of setting a fashion; no thought that my action would create an excitement throughout the civilized world, and give to the style my name and the credit due Mrs. Miller. This was all the work of the press. I stood amazed at the furor I had unwittingly caused. The New York Tribune contained the first notice I saw of my action. Other papers caught it up and handed it about.

My exchanges all had something to say. Some praised and some blamed, some commented, and some ridiculed and condemned. “Bloomerism,” “Bloomerites,” and “Bloomers” were the heading of many an article, item, and squib; and finally someone—I don’t know to whom I am indebted for the honor—wrote the “Bloomer Costume,” and the name has continued to cling to the short dress in spite of my repeatedly disclaiming all right to it and giving Mrs. Miller’s name as that of the originator or the first to wear such dress in public. Had she not come to us in that style, it is not probable that either Mrs. Stanton or myself would have donned it. 2

Currier & Ives, The Bloomer Costume

During the summer of 1851, the nation was seized by a “bloomer craze.” Women from Laramie, Wyoming to London, England, embraced the freedom of the new outfit and rejoiced. A million versions of the blouse, skirt, and pants combo emerged. Managers of the textile mills in Lowell, Massachusetts, gave a banquet for any of their female workers who adopted the safer dress before July 4. In Toledo, Ohio, sixty women turned out in Turkish costume at one of the city’s grandest social events. Bloomer balls and bloomer picnics were held; dress reform societies and bloomer institutes were formed. The craze inspired music to be composed.

The Bloomer outfit became a symbol of women’s emancipation. Thousands of women were soon wearing the reform dress.

But then the tide turned. Controversy erupted. There were laws in some American cities that made it illegal for a person to dress in the clothes of the opposite sex. At the time, pants were considered the domain of the American male, which was also the right to vote. Backlash from men ensued. The movement for a sharing of pants was viewed, in some quarters, as a threat to male power. 3

The same newspapers that had once celebrated the trend as tasteful and elegant were, by August of 1851, scorning it. Public meetings were called to denounce the fad. Some young women were turned away from church membership for wearing the dress. The satirical London magazine Punch lampooned the Bloomers.

The term “Bloomerism” came to be associated not just with wearing trousers but also with other supposedly deviant and negative (for women) behaviors, such as smoking, drinking, gambling, serving in the military, and abandoning husbands and children. Punch cartoon, 1851, artist, John Leech

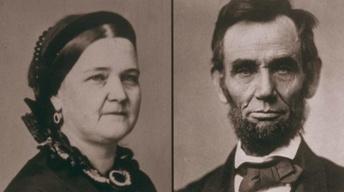

Elizabeth Cady Stanton with daughter, Harriot, 1856-57

Although Elizabeth Cady Stanton had felt at first “as joyous and free as some poor captive who has just cast off his ball and chain” when adopting the Bloomer costume, her young sons didn’t want to be seen with her. Her father banned the Bloomer costume from his house. Her older sister cried and her brother-in-law, a senator, said that “some good Democrats said they would not vote for a man whose wife wore the Bloomers.” After two years, Stanton gave up the Bloomers. “Had I counted the cost of the short dress,” Stanton told cousin Libby Miller, “I would never have put it on.” 4

Although Amelia Bloomer “had found the dress comfortable, light, easy, and convenient, and well adapted to the needs of my busy life,” after wearing it six to eight years, she, too, laid it aside and returned to long skirts. Bloomer wrote:

We all [women’s right activists] felt that the dress was drawing attention from what we thought of far greater importance—the question of woman’s right to better education, to a wider field of employment, to better remuneration for her labor, and to the ballot for the protection of her rights. In the minds of some people, the short dress and woman’s rights were inseparably connected. With us, the dress was but an incident, and we were not willing to sacrifice greater questions to it. 5