Upon return from her trip around the world, Nellie published an account of her travels

When we last left Nellie Bly, it was November 14, 1889 (see blog entries for Feb. 11 and 12) and she had just departed New York for Southhampton, England, on an ocean steamer. In the next thirteen days, Nellie crossed the Atlantic, took a train to London, a boat across the English Channel to Calais, France, and a train through France and Italy. In Brindisi, Italy, she caught another steamer for China, the Victoria. Along the way, she wrote an account of her travels and cabled them back to her editor at the New York World for publication. The trip caused a sensation back home as readers followed her adventures with relish.

Thirteen days into her journey, the steamer Victoria anchored at Port Said, Egypt, to take on coal. Nellie and her fellow passengers gathered on deck and gazed out on a wide, sandy beach and a few uninteresting houses. They gladly welcomed a change of scenery, though, and looked forward to some time on shore. Here is her account of that experience as recorded later in the book she wrote upon her return, Around the World in Seventy-Two Days:

Before the boat anchored the men armed themselves with canes, to keep off the beggars they said; and the women carried parasols for the same purpose. I had neither stick nor umbrella with me, and refused all offers to accept one for this occasion, having an idea, probably a wrong one, that a stick beats more ugliness into a person than it ever beats out.

Hardly had the anchor dropped than the ship was surrounded with a fleet of small boats, steered by half-clad Arabs, fighting, grabbing, pulling, yelling in their mad haste to be first. I never in my life saw such an exhibition of hungry greed for the few pence they expected to earn by taking the passengers ashore. Some boatmen actually pulled others out of their boats into the water in their frantic endeavors to steal each other’s places. When the ladder was lowered, numbers of them caught it and clung to it as if it meant life or death to them, and here they clung until the captain was compelled to order some sailors to beat the Arabs off, which they did with long poles, before the passengers dared venture forth. This dreadful exhibition made me feel that probably there was some justification in arming one’s self with a club.

Our party were about the first to go down the ladder to the boats. It had been our desire and intention to go ashore together, but when we stepped into the first boat some were caught by rival boatmen and literally dragged across to other boats. The men in the party used their sticks quite vigorously; all to no avail, and although I thought the conduct of the Arabs justified this harsh course of treatment, still I felt sorry to see it administered so freely and lavishly to those black, half-clad wretches, and marveled at their stubborn persistence even while cringing under the blows. Having our party divided there was nothing to do under the circumstances but to land and reunite on shore, so we ordered the Arabs to pull away. Midway between the Victoria and the shore the boatmen stopped and demanded their money in very plain and forcible English. We were completely at their mercy, as they would not land us either way until we paid what they asked. One of the Arabs told me that they had many years’ experience in dealing with the English and their sticks, and had learned by bitter lessons that if they landed an Englishman before he paid they would receive a stinging blow for their labor.

Yesterday, you will recall, we followed famed stunt reporter Nellie Bly as she tried to convince her editor to let her make a journalistic trip

Yesterday, you will recall, we followed famed stunt reporter Nellie Bly as she tried to convince her editor to let her make a journalistic trip

In Nellie Bly’s book, Ten Days in a Mad-House (see category, “Nellie Bly,” for related posts), Nellie Bly described various women she met in the Blackwell Island Women’s Lunatic Asylum. She was confined to Hall 6 with 45 of the least dangerous women in the institution. While some of them were certifiably “crazy,” (her words), many, she felt, had been wrongly locked up. A Frenchwoman, for example, named Josephine Despreau, fell sick in a boarding house and the woman of the house called in the police. They arrested her and took her to the station-house. She didn’t understand the proceedings because of the language barrier and the judge paid no attention to her protests. She was locked up in the insane asylum in no time.

In Nellie Bly’s book, Ten Days in a Mad-House (see category, “Nellie Bly,” for related posts), Nellie Bly described various women she met in the Blackwell Island Women’s Lunatic Asylum. She was confined to Hall 6 with 45 of the least dangerous women in the institution. While some of them were certifiably “crazy,” (her words), many, she felt, had been wrongly locked up. A Frenchwoman, for example, named Josephine Despreau, fell sick in a boarding house and the woman of the house called in the police. They arrested her and took her to the station-house. She didn’t understand the proceedings because of the language barrier and the judge paid no attention to her protests. She was locked up in the insane asylum in no time.

ellie Bly was put on the island boat and sent to Blackwell’s Island. For ten days, she experienced firsthand the horrors of being locked up in cruel and inhumane conditions. Upon her arrival, she was fed a disgusting meal of pink watery tea, prunes, and bread that was dirty and black and mostly dried dough. She found a spider in the slice given her. She didn’t eat it. Later she learned that the nurses didn’t like it when you didn’t eat your food. They might beat you for that.

ellie Bly was put on the island boat and sent to Blackwell’s Island. For ten days, she experienced firsthand the horrors of being locked up in cruel and inhumane conditions. Upon her arrival, she was fed a disgusting meal of pink watery tea, prunes, and bread that was dirty and black and mostly dried dough. She found a spider in the slice given her. She didn’t eat it. Later she learned that the nurses didn’t like it when you didn’t eat your food. They might beat you for that.

One day, during my stay in New York, I paid a visit to the different public institutions on Long Island, or Rhode Island: I forget which. One of them is a Lunatic Asylum. The building is handsome; and is remarkable for a spacious and elegant staircase. The whole structure is not yet finished, but it is already one of considerable size and extent, and is capable of accommodating a very large number of patients.

One day, during my stay in New York, I paid a visit to the different public institutions on Long Island, or Rhode Island: I forget which. One of them is a Lunatic Asylum. The building is handsome; and is remarkable for a spacious and elegant staircase. The whole structure is not yet finished, but it is already one of considerable size and extent, and is capable of accommodating a very large number of patients.

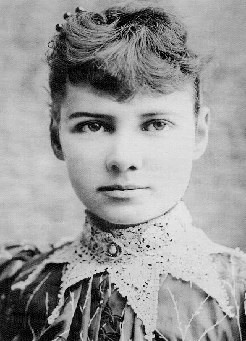

“So I flew to the mirror and examined my face,” she wrote later. “I remembered all I had read of the doings of crazy people, how first of all they have staring eyes, and so I opened mine as wide as possible and stared unblinkingly at my own reflection.” She began to sweat nervously, which unfortunately took the curl out of her Victorian bangs. Over and over again, she practiced her crazy face in the mirror. She ended up staying up all night, rehearsing her new role, thinking about her new mission, and reading scores of ghost stories to put her in a lunatic frame of mind.

“So I flew to the mirror and examined my face,” she wrote later. “I remembered all I had read of the doings of crazy people, how first of all they have staring eyes, and so I opened mine as wide as possible and stared unblinkingly at my own reflection.” She began to sweat nervously, which unfortunately took the curl out of her Victorian bangs. Over and over again, she practiced her crazy face in the mirror. She ended up staying up all night, rehearsing her new role, thinking about her new mission, and reading scores of ghost stories to put her in a lunatic frame of mind. It had been four months since she’d left Pittsburgh for New York yet Elizabeth Jane Cochran, or “Nellie Bly,” as her byline read, still hadn’t landed a job as a newspaper reporter. She had left the Pittsburgh Dispatch because she was tired of being assigned to the ladies’ pages – writing the society column, reviewing operas, and reporting on the latest women’s fashions.

It had been four months since she’d left Pittsburgh for New York yet Elizabeth Jane Cochran, or “Nellie Bly,” as her byline read, still hadn’t landed a job as a newspaper reporter. She had left the Pittsburgh Dispatch because she was tired of being assigned to the ladies’ pages – writing the society column, reviewing operas, and reporting on the latest women’s fashions.