"Madame X" by American portrait painter John Singer Sargent, 1884

In the Metropolitan Museum of New York hangs a seven-foot tall portrait of a rather pale woman in a black velvet evening dress held up by sparkly straps. “Madame X” was painted by the American society painter John Singer Sargent. The subject of the painting is Madame Virginie Gautreau, a professional beauty, who moved in the top tiers of Paris society and was often mentioned in the scandal sheets for her numerous dangerous indiscretions and passion for self-display. It was 1884 and Madame Gautreau was the Talk of Paris.

It was only a year earlier that John Singer Sargent had met her at a party. Once he laid eyes on her, he knew at once he must paint a portrait of her as an homage to her beauty – and a boost to his lagging career. He felt that if he painted her, all Parisian society women would flock to his studio demanding that he paint their portraits. Sargent sent word to Madame Gautreau that she must sit for a portrait; she consented, realizing that a rising tide lifts all boats. She, too, needed the publicity to maintain her social superiority. Once they agreed, Sargent began to paint, devoting himself to capture the “strange, weird, fantastic, curious beauty of that peacock-woman, Mme. Gautreau,” noted one observer.

Madame Gautreau was rumored to take great pains to be beautiful:

Gautreau achieved her affected, highly artificial look with hennaed hair, heavily penciled brows, rouged ears and powdered skin. She was rumored to mix her powder with mauve tint and to ingest arsenic wafers to make her skin more translucent, giving it even more of a bluish-purple tint.

Not all thought she was lovely to look at. She had her detractors. Some said her white pallor and icy charm made her resemble a cadaver.

"Madame X" is shown as it must have originally appeared

The painting that hangs in the Met today, “Madame X,” however, is not the same Madame X as the one that Sargent painted in 1884 and exhibited in Paris. That image no longer exists. We can only speculate what it looked like. The painting shown to the right here is what it may have looked like. That original, the one exhibited in Paris in 1884, showed Madame Gautreau’s dress with the right strap suggestively falling off her shoulder. (Compare to the painting at the top, the one at the Met. Her right strap, you’ll notice, sits firmly in place.)

When exhibited in Paris, the painting “with the falling strap” created an instant sensation but not in the way Sargent and Gautreau had hoped:

No sooner had the doors of the Palais de l’Industrie in the Champs-Élysées opened on May 1, 1884, than a crowd gathered in front of ”Madame X.” People hooted and pointed the tips of their umbrellas and canes at the painting. ”Look! She forgot her chemise!*” was heard over and over again. The critics were no kinder. ”Of all the undressed women at the Salon this year, the most interesting is Madame Gautreau . . . because of the indecency of her dress that looks like it is about to fall off,” wrote a critic for L’Artist. (*A chemise is a woman’s undergarment, a smock, that is worn under clothing and next to the skin. In that day, a French lady always wore a chemise under a dress.)

The painting was considered too provocative; sex pervaded it. Not even an actress, it was remarked, would wear a dress that shockingly low-cut and snug! And that strap! A little imagination conjured up a scene in which a slight struggle with a lover might knock Madame X’s right strap completely off her shoulder leading to… ! Paris was abuzz with the scandal. Madame Gautreau’s mother demanded that Sargent withdraw the painting from the exhibit. He refused.

John Singer Sargent in Paris studio 1885 with the revised painting of Madame X

The painting, considered a beloved masterpiece today but pornographic by 1884 Parisian standards of decency, was trashed by the Paris critics so badly that Sargent, having lived in Paris for a decade then, was eventually forced to move to London to continue his profession. Sargent revised the painting to show the gown’s right strap securely in place. It is this retouched painting that hangs in the New York Metropolitan today.

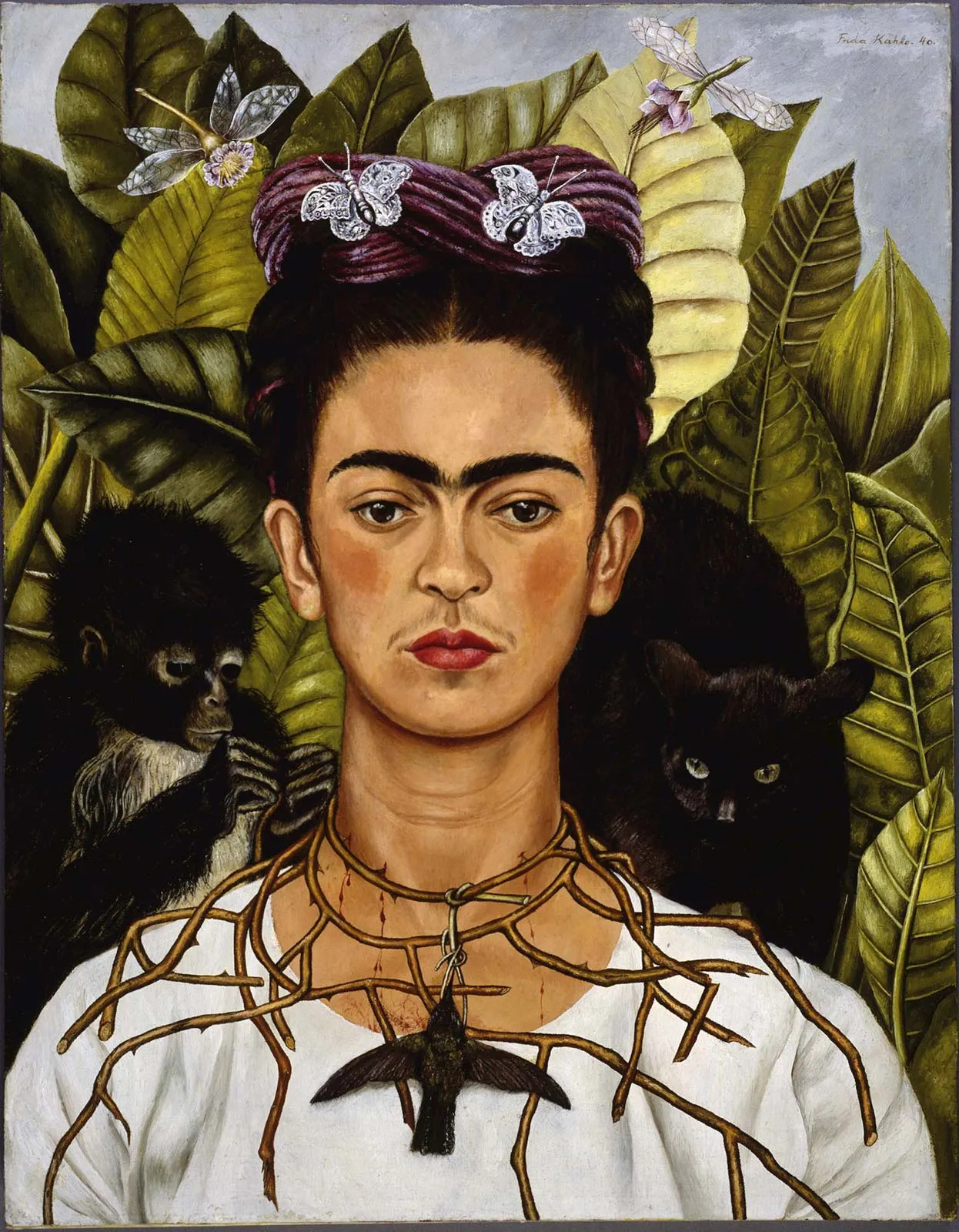

Zip ahead to 1938 and the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Dorothy Hale was wearing her Madame X dress when she jumped to her death from her penthouse apartment. To learn more, read “Frida Kahlo: The Suicide of Dorothy Hale.”

"The Suicide of Dorothy Hale" by Frida Kahlo, 1938/39