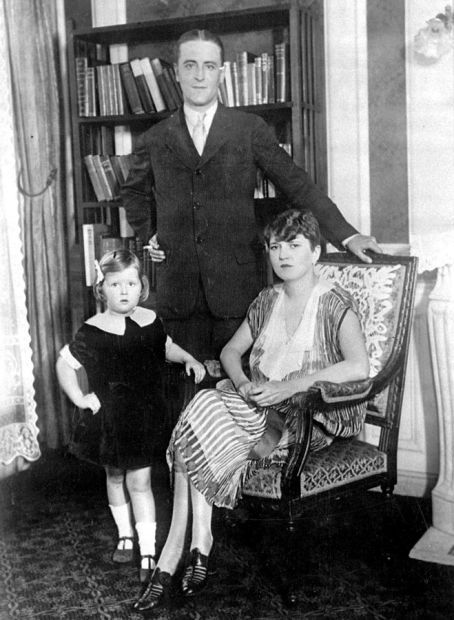

The Fitzgeralds in their Paris apartment, 1926. “Scottie,” age 5, Scott, and Zelda

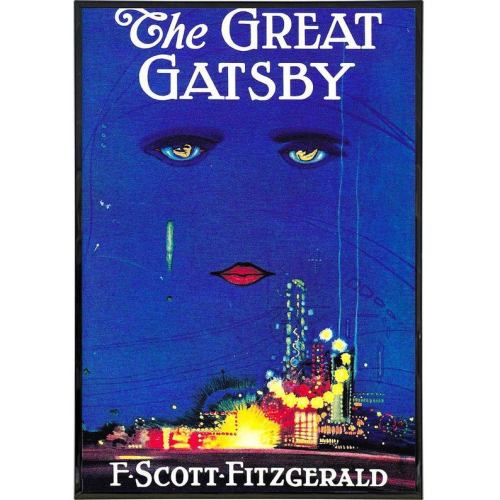

Zelda Fitzgerald‘s health improved greatly following an appendectomy in June of 1926 in the American hospital in Neuilly outside of Paris. Unfortunately, the same could not be said of her husband, American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940). Although his recently-published novel, The Great Gatsby (1925), had received mostly positive reviews from literary critics, it was not selling well.

While Zelda (1900-1948) was still hospitalized, Sara Mayfield, Zelda’s childhood friend from Montgomery, Alabama, ran into Scott in Paris. She was having drinks with the son of the Spanish ambassador to the United States and Michael Arlen, whose novel, The Green Hat, was creating a sensation abroad. Scott joined them at their table. At first, the conversation flowed pleasantly. Scott complimented Arlen on his literary success. A half hour and more drinks later, the conversation turned to the writing of Ernest Hemingway. Arlen did not think highly of it. Scott considered Hemingway his great friend and a great writer. Scott pounced on Sara’s friend, accusing Arlen of being

While Zelda (1900-1948) was still hospitalized, Sara Mayfield, Zelda’s childhood friend from Montgomery, Alabama, ran into Scott in Paris. She was having drinks with the son of the Spanish ambassador to the United States and Michael Arlen, whose novel, The Green Hat, was creating a sensation abroad. Scott joined them at their table. At first, the conversation flowed pleasantly. Scott complimented Arlen on his literary success. A half hour and more drinks later, the conversation turned to the writing of Ernest Hemingway. Arlen did not think highly of it. Scott considered Hemingway his great friend and a great writer. Scott pounced on Sara’s friend, accusing Arlen of being

a finished second-rater that’s jealous of a coming first-rater.”

Someone diffused the situation and steered Scott off the subject. Then Scott was on his way to the hospital to see Zelda and asked Sara Mayfield if she would join him. She agreed. First, however, he decided he wanted to have dinner. He wanted to find Hemingway who may have returned from seeing the running of the bulls in Pamplona, Spain. He and Sara stopped at Harry’s New York Bar. Things turned nasty quickly. A newspaper man asked Scott if he was promoting Hemingway. Scott somehow got offended and wanted to punch the newspaper man. Fortunately, someone interceded and stopped him.

Sara and Scott never did get around to visiting Zelda. Scott got roaring drunk and passed out in the fresh food market, Les Halles.

More and more, Scott’s nights and days were passed in this way: no work done, drinking, and talking with friends, passing out and being put into a taxi and sent home alone.”

Once Zelda was sufficiently recovered from her surgery, the Fitzgeralds were back in the South of France in the area known as the French Riviera for the rest of that summer.

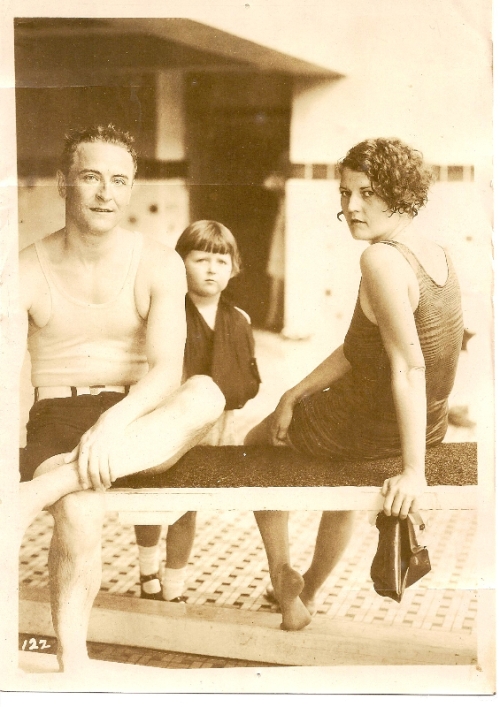

The Fitzgeralds ca. 1927. photo courtesy Mary A. Doty.

One evening in August, they were dining with two other American expatriates, Sara and Gerald Murphy in the hills above the Mediterranean near Nice, France in St. Paul-de-Vence at La Colombe D’Or.

St. Paul-de-Vence is located where you see the red marker, approximately 20 km southwest of Nice in the hills.

St. Paul-de-Vence, South of France

La Colombe d’Or was a quaint and popular roadside bistro frequented by artists like Picasso, who sometimes paid for his meal with drawings. The open-air terrace restaurant is set on the edge of the ramparts of the ancient Roman hilltop town of Saint-Paul-de-Vence.

That August evening, the Murphys had reserved a table for four on the elevated stone terrace overlooking the Loup Valley, two hundred feet below.

A view from the open-air terrace of the hotel/restaurant La Colombe d’Or. Image from the book La Colombe d’Or: Saint Paul De Vence

La Colombe D’Or today, a restaurant and hotel

Midway through the meal, Gerald noticed that the famous American dancer, Isadora Duncan (1878-1927), was sitting at a table nearby along with three of her admirers. Gerald pointed her out to Scott and he and Sara told Scott who she was.

Now 48 years old, Isadora was no longer the lithe young dancer who had revolutionized the dance world by eschewing the rigidity of traditional ballet. In her heyday as a dancer who toured the globe, Isadora Duncan abandoned the plié, stiff-toed pointe shoes, and the tutu, preferring free form movement—skipping about in meadows and on beaches, barefoot, bare-legged, fluttering her arms about, wearing loose and flowing Greek tunics with long scarves trailing and billowing behind her.

Isadora Duncan dances for the Italian War Relief Fund during World War I. (Photo by George Rinhart/Corbis via Getty Images) 1917

Now 48 years old, Isadora was hugely fat and her dissipated life was legend. Her hair was dyed with henna.

Nevertheless, Isadora Duncan still had star power. Scott, enamored of fame, rushed over to introduce himself to her. He crouched at her side. He praised her artistry. Knowing that Scott was a writer, she divulged to him that she had a contract to write her memoirs; she had received a cash advance. As a result, she was being pressured to complete and submit the manuscript to her editor and, frankly, she was stuck. Scott offered to help. She wrote down her hotel and room number and handed this note to Scott. Scott was still fawning at her feet. Isadora reached down and began running her hands through his hair. She called him a centurion, her protective soldier.

At this point, Zelda, observing this scene, stood up on her chair, and, without warning, leaped over the table—and over Gerald, who was sitting with his back to the valley view—and dove into the darkness beyond and below the terrace. (Zelda was a proficient diver and swimmer.)

I was sure she was dead,”

recalled Gerald.

Shortly, Zelda reappeared. She had fallen down a stone staircase than ran down the hillside. Her knees and dress were bloody. Otherwise, she was remarkably all in one piece. Sara grabbed her napkin, flew to Zelda’s side, and began wiping away the blood. Gerald’s first thought was

that it had not been ugly. I said that to myself over and over again.”

Zelda Fitzgerald’s behavior would grow more and more peculiar and yet she would live another twenty-two years. In the fall of 1927, she returned to her childhood study of ballet and it became an obsession. She would practice 6-8 hrs a day to the point of exhaustion and a weight loss of 15 pounds.

Zelda in ballet costume, 1929.

In 1930, she suffered a mental breakdown and was hospitalized in Paris. From then on, she would drift in and out of various mental institutions in Switzerland, France, and the United States. She endured grueling and often inhumane and certainly experimental treatment for her diagnosis of “schizophrenia.” She would make progress and then exit the institution before, reliably, suffering setbacks and needing to be readmitted to the hospital. Her mental health spiraled downhill.

Fitzgerald, in his own words, “just couldn’t make the grade as a hack” writing Hollywood scripts for MGM. Illustration by Barry Blitt for the New Yorker.

Meanwhile, Scott’s party drinking had exploded into full-blown alcoholism. He found it harder and harder to write in those gin-soaked years. But their daughter, Scottie, had expenses and Zelda’s hospitalizations cost a fortune so he had to write to make money. He wrote until the end of his days, although suffering ill health all the while. He died of a heart attack in Hollywood at the age of 44.

Isadora Duncan, ca. 1903, wearing a signature neck scarf

After having met Scott Fitzgerald on the terrace of La Colombe D’Or, Isadora Duncan would live another full year. On the night of September 14th, 1927, she was riding in a open-top car with a friend in Nice, France, when the long, silk scarf she was wearing—her signature look was her long, silk scarf— became entangled in the spoke of one of the rear wheels, breaking her neck, dragging her backwards, and killing her instantly.

According to dispatches from Nice, Duncan was hurled in an extraordinary manner from an open automobile in which she was riding and instantly killed by the force of her fall to the stone pavement.”

Upon learning of Duncan’s tragic death by strangulation, the poet and Nazi collaborator Gertrude Stein acidly remarked:

affectations can be dangerous”

Sources:

Vaill, Amanda. Everybody Was So Young (1998).

Bruccoli, Matthew J. Some Sort of Epic Grandeur: The Life of F. Scott Fitzgerald (1981).

Milford, Nancy. Zelda (1970).

Taylor, Kendall. The Gatsby Affair: Scott, Zelda, and the Betrayal that Shaped an American Classic (2018).

O’Neill, Frances; Rennie, David Alan. F. Scott Fitzgerald in Provence-A Guide (2018).

The New York Times. 1927-09-15

In 1939, France declared war on Nazi Germany for its invasion of Poland. Within nine months, the Nazis invaded France. Baker was recruited by the Deuxiéme Bureau, the French Military Intelligence, as an “honorable correspondent.” She was so well-known and popular that even the Nazis were hesitant to cause her harm. She made the perfect spy. As an entertainer, she had good excuses for traveling, which allowed her to smuggle secret orders and maps written in invisible ink on her musical sheets. On some occasions, Baker would smuggle secret photos of German military installations out of enemy territory by pinning them to her underwear. To operatives in the French Resistance as well as U.S. and British agents, she relayed information on German troop movements she had gleaned from conversations she overheard between officials with whom she mingled following her performances or at embassy and ministry parties. She also exposed French officials working for the Germans. She hid Jewish refugees and weapons in her 24-room château in the South of France.

In 1939, France declared war on Nazi Germany for its invasion of Poland. Within nine months, the Nazis invaded France. Baker was recruited by the Deuxiéme Bureau, the French Military Intelligence, as an “honorable correspondent.” She was so well-known and popular that even the Nazis were hesitant to cause her harm. She made the perfect spy. As an entertainer, she had good excuses for traveling, which allowed her to smuggle secret orders and maps written in invisible ink on her musical sheets. On some occasions, Baker would smuggle secret photos of German military installations out of enemy territory by pinning them to her underwear. To operatives in the French Resistance as well as U.S. and British agents, she relayed information on German troop movements she had gleaned from conversations she overheard between officials with whom she mingled following her performances or at embassy and ministry parties. She also exposed French officials working for the Germans. She hid Jewish refugees and weapons in her 24-room château in the South of France.