Prince Philip, 97, takes a carriage ride through the grounds of Windsor Castle. ca. October 20, 2018

As I mentioned in my blog post, “Prince Philip’s Mum had a Habit,” Prince Philip of the United Kingdom, known as the Duke of Edinburgh, the Prince Consort of Queen Elizabeth II, was born in 1921 on a kitchen table in Corfu, Greece, in a house that had no electricity or running water. But Philip was not of peasant stock. He was Prince Philip of Greece, born into a royal family with ties to German, British, Dutch, Russian, and Danish royal houses. Oddly enough, however, neither Philip’s parents nor his four beautiful sisters had a drop of Greek blood in them. Yet they were a branch of the Greek Royal Family.

Prince Philip’s mother was Princess Alice of Battenberg. Alice’s great grandmother, Queen Victoria of England, had been present at her birth in the Tapestry Room at Windsor Castle in England. Philip’s father, Prince Andrew of Greece and Denmark, had been born in Athens, Greece. The two married in 1903 in Germany, the native country of Princess Alice’s parents.

Princess Alice of Battenberg and Prince Andrew of Greece, ca. their wedding 1903

Head spinning yet? There’s a reason Queen Victoria of England is called “the grandmother of Europe.” Her descendants fanned across the continent. She and other royal matriarchs and patriarchs were quite the matchmakers, shoring up old alliances and creating new ones, through arranged royal marriages. This proved to be a problem both health wise (hemophilia) and when European countries found themselves warring with one another, especially during both World War I and II, pitting blood relatives against one another in deadly warfare, a confusion of loyalties.

But I digress. My goal today is to shed some light on Princess Alice (1885-1969) and her struggle with mental illness. Alice was born with a large disadvantage in life: she was deaf. She learned to lip read and speak English and German. She studied French and, after her engagement to Prince Andrew, began to learn Greek.

Her husband, Prince Andrew (1882-1944), a military man, was a polyglot. His caretakers taught him English as he grew up, but he insisted upon speaking only Greek with his parents. He also spoke Danish (his father was originally a Danish prince), French, German, and Russian (his mother was Russian—a Romanov). Alice had spent her early years between her family homes in England and Germany whereas Andrew’s roots were in Denmark and Russia. She was Lutheran, although others say she was Anglican. He was Greek Orthodox.

Andrew—known to his friends and family as “Andrea”—had hoped that he and his new bride Alice could settle down permanently in Greece. From the beginning of their marriage, though, Prince Andrew and his family’s safety within Greece waxed and waned. The Greek political situation was always unstable. Prince Andrew fell in and out of favor with the reigning political parties. One moment he was forced to resign his army post and then, in 1912 during the Balkan Wars, he was reinstated. It was during the Balkan Wars that Princess Alice—sometimes referred to as “Princess Andrew”—acted as a nurse, assisting at operations and setting up field hospitals, work for which King George V of Great Britain awarded her the Royal Red Cross in 1913.

Writing to her mother, Victoria, Marchioness of Milford Haven, on November 2, 1912, Alice recalled a scene at a field hospital following the arrival of wounded soldiers from a victorious battle by the Greeks at Kailar:

Our last afternoon at Kozani was spent in assisting at the amputation of a leg. I had to give chloroform at a certain moment and prevent the patient from biting his tongue and also to hand cotton wool, basins, etc. Once I got over my feeling of disgust, it was very interesting….[A]fter all was over, the leg was forgotten on the floor and I suddenly saw it there afterwards and pointed it out to Mademoiselle Agyropoulo, saying that somebody ought to take it away. She promptly picked it up herself wrapped it up in some stuff, put it under her arm and marched out of the hospital to find a place to bury it in. But she never noticed that she left the bloody end uncovered, and as she is as deaf as I, although I shouted after her, she went on unconcerned, and everybody she passed nearly retched with disgust—and, of course, I ended by laughing, when the comic part of the thing struck me.”

The next day, Alice’s mother’s lady-in-waiting, Nona Kerr, arrived in Greece. She went to see Alice. Nona then wrote a letter to Alice’s mother, telling her how Alice seemed. Nona wrote to Victoria that it “would make you proud to hear the way everyone speaks of Princess Alice. Sophie Baltazzi, Doctor Sava, everyone. She has done wonders.” She also noted that Alice was “very thin…At present she simply can’t stop doing things. Prince Andrew wants to send her back to Athens to the babies [Alice and Andrew had three daughters by then: Margarita (b. 1905), Theodora (b. 1906), Cécile (b. 1911)] soon, but I don’t think he will succeed just yet….” Alice was suffering from mania, probably triggered by sleep deprivation, hunger, cold, exposure, and PTSD.

During the war, Andrew’s father was assassinated and he inherited a villa on the island of Corfu, Mon Repos. The family moved there.

In June of 1914, Alice gave birth to a fourth daughter, Sophie.

Margarita, Theodora, Cecilie and Baby Sophie in 1914

One month later, World War I broke out across Europe. Andrew’s brother, King Constantine of Greece, declared the neutrality of his country. However, the Greek ruling party sided with the Allies. During the war, Prince Andrew, unwisely, made several visits to Great Britain, one of the Allied countries. Rumors circulated in the British House of Commons that Andrew was a German spy. This stirred up suspicions in Greece. Was Prince Andrew indeed a spy for the Central Powers?

Prince Andrew and Princess Alice of Greece, 1916. Note Prince Andrew’s right eye monocle.

By 1917, the whole Greek royal family was forced to flee Greece, as they were suspected of consorting with the enemy. Most of the Greek royals, including Alice and Andrew and their family, took refuge in Lucerne, Switzerland. At the end of the war, in July of 1918, Alice’s two maternal aunts, Tsarina Alexandra (Alix) and the Grand Duchess Elizabeta Feodorovna (Ella), were killed by the Bolsheviks in the Russian Revolution.

So much suffering and tragedy, living in constant fear, doomed to exist in a world devoid of sound, living here, traveling there, led Alice to seek comfort in mystic religion. Together with her brother-in-law Christo, they performed automatic writing, a precursor to the use of a ouija board to receive supernatural messages from the spirit world. Alice was superstitious. She was often seen dealing herself cards and getting messages from this, especially when she had important decisions to make. She continued to read books on the occult.

After three years in Swiss exile, the political situation in Greece became more favorable to the Royals. In 1920, the Greek Royal family was invited to return home. Prince Andrew and Princess Alice happily re-established themselves and their family in their peaceful villa, Mon Repos. But the country was still in turmoil. Greece was embroiled in another regional military conflict, The Greco-Turkish War, AKA The Asia Minor Campaign. Prince Andrew was put in command of The II Army Corps.

All of this instability had transpired before their son Prince Philip was born on June 10, 1921, at Mon Repos. Prince Andrew was not present for his first son’s birth as he was on the battlefield.

Princess Alice of Greece holds newborn Prince Philip of Greece. June/July 1921

Prince Andrew of Greece and Denmark holds his fifth child and only son, Prince Philip of Greece, born June 10, 1921.

Fast forward a year or so. The October 27, 1922 headlines in the New York Times read:

SEIZE PRINCE ANDREW FOR GREEK DEBACLE

Constantine’s Brother to Be Interned at Athens

New Tribunal Arrests Four Others

The Greek defeat in Asia Minor in August 1922 had led to the September 11, 1922 Revolution, during which Prince Andrew was arrested, court-martialed, and found guilty of “disobeying an order” and “acting on his own initiative” during the battle the previous year. Many defendants in the treason trials that followed the coup were shot by firing squad and their bodies dumped in holes on the plains at Goudi, below Mount Hymettus. British diplomats assumed that Andrew was also in mortal danger. They called upon King George V of England to act. However, King George V refused to risk inflaming the situation further, causing an international incident, by allowing Andrew to settle in London. In December of 1922, he sent the British cruiser, HMS Calypso, to ferry Andrew’s family to France. Andrew, though spared the death sentence, was banished from Greece for life. Eighteen month-old Philip was transported in an improvised cot made from an orange crate. The family settled at Saint-Cloud on the outskirts of Paris, in a small house loaned to them by Andrew’s generous sister-in-law, Princess Marie Bonaparte, AKA Princess George of Greece. Andrew and his family were stripped of their Greek nationality, and traveled under Danish passports.

Princesses Sophie, Cecilie, Theodora, and Margarita of Greece, sisters of Prince Philip of Greece. ca. 1922

Alice and Andrew celebrated their silver wedding anniversary on October 8, 1928. Each member of the family had made it a point to be at Saint Cloud that beautiful autumn day so they could commemorate the special event with a group photograph in the garden.

Prince Philip poses with his family for a photograph to mark his parents’ silver wedding anniversary in October of 1928. A young Philip stands to the right of his mother, Princess Alice, and father, Prince Andrew of Greece and Denmark. From left to right are Philip’s sisters, all Princesses of Greece & Denmark: Margarita, Theodora, Sophie, and Cecilie.

Five years into exile, the family of six often found themselves more apart than together, traveling a lot, scattered across the European continent, staying with relatives, enjoying the London social season, on holiday, or attending a royal funeral or wedding. It was an idle life which had no real purpose.

Two weeks after the anniversary, Alice privately gave up her Protestant faith and became a member of the Greek Orthodox Church. By May of 1929, she had become “intensely mystical,” and would lie on the floor so that she could receive divine messages. She told others that she could heal with her hands. She said she could stop her thoughts like a Buddhist. Her husband stayed away that summer and would not return until September. Alice wrote her mother that soon she would have a message to tell the world. She told Andrew’s cousin that she, Alice, was a saint. She carried sacred objects around the house with her in order to banish evil influences. She proclaimed she was the “bride of Christ.”

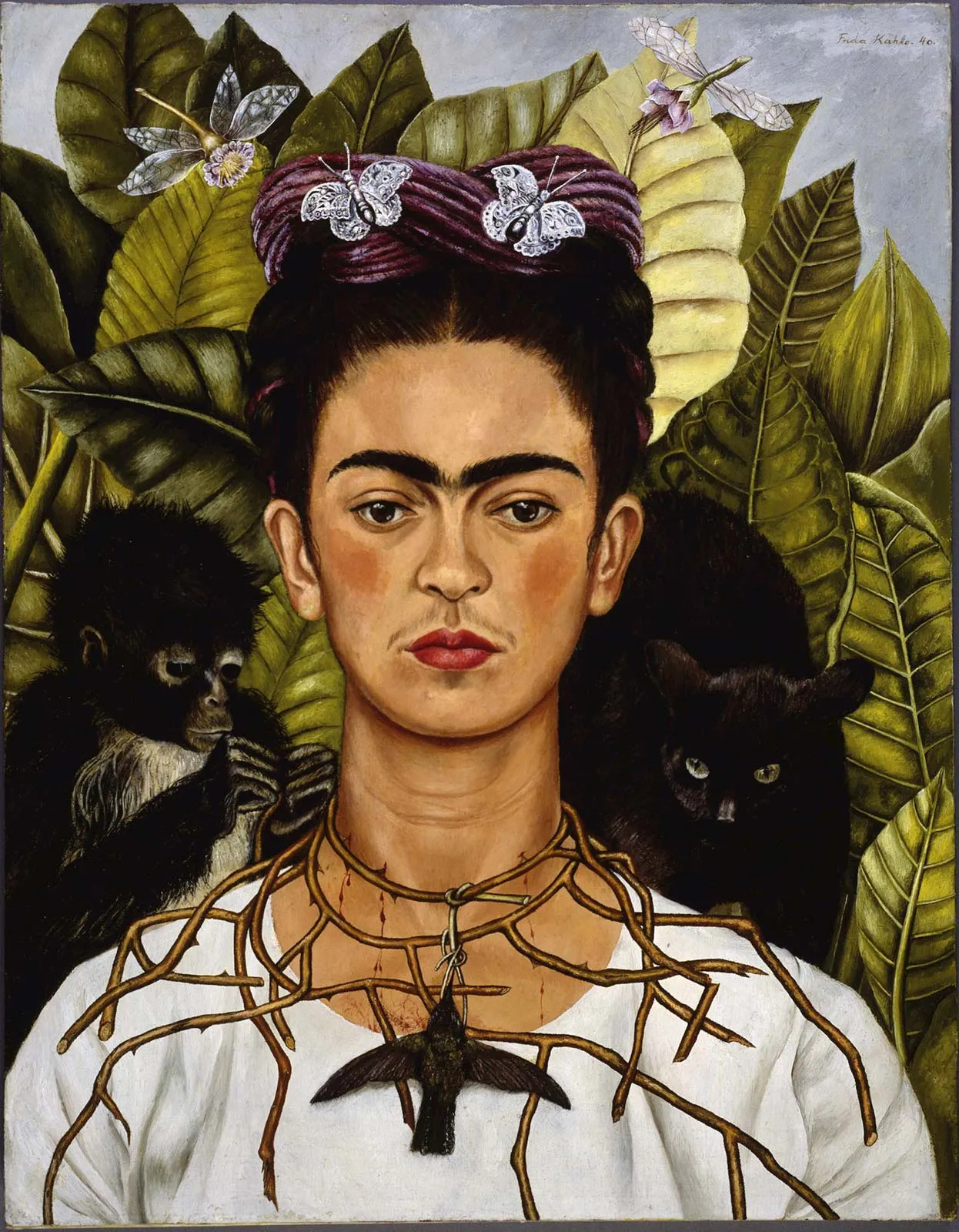

Andrew and Alice’s mother Victoria summoned Alice’s gynecologist who diagnosed her psychosis. Her sister-in-law the French Princess Marie Bonaparte, a great friend of the famous psychoanalyst Dr. Sigmund Freud, arranged for Alice to see one of Freud’s former co-workers, the psychoanalyst Dr. Ernst Simmel, just outside Berlin. Dr. Louros accompanied Alice in her journey and she was admitted to Simmel’s clinic. Dr. Simmel diagnosed Alice as “paranoid schizophrenic” and said she was suffering from a “neurotic-prepsychotic libidinous condition” and consulted Freud about it. Freud advised “an exposure of the gonads [ovaries] to X-rays, in order to accelerate the menopause,” presumably to calm her down. Was Alice consulted about this? Probably not. The treatment was carried out.

Alice did not improve. On May 2, 1930, she was involuntarily committed at the Bellevue private psychiatric clinic at Kleuzlingen in Switzerland. This event marked the end of their once-close family life. Though they did not divorce, Alice and Andrea’s marriage was effectively finished. Andrew closed the family home at Saint-Cloud and disappeared, moving to the South of France, where he frittered away his life drinking, gambling, and womanizing. The girls were ages 16, 19, 24, and 29, and would all be married by 1932, so they were less affected by the fallout of their mother’s breakdown and their father’s abdication of his family role. Unfortunately, two of the girls ended up marrying German Nazis. Philip, though, was only nine years old when his mother was institutionalized and his father abandoned him. Philip would have little contact with his mother for the rest of his childhood which was spent living with his mother’s relatives in England and in attending boarding schools in England, Germany, and Scotland.

Prince Philip of Greece, 1930 (AP)

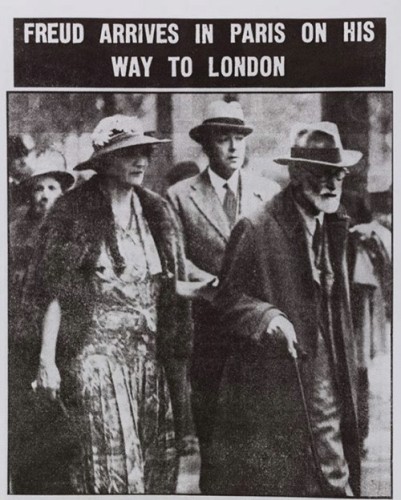

Footnote: Philip’s aunt, Princess Marie Bonaparte, who had arranged for Princess Alice to be treated by Freud and his colleague, was very wealthy and influential. Her mother had owned the casino in Monte Carlo and Princess Marie had inherited this money. As you will remember, Marie had very generously provided Alice and Andrea with their house at Saint Cloud. In 1938, Princess Marie Bonaparte paid the Nazis a ransom of 12,000 Dutch guilders to allow Dr. Sigmund Freud and his family the freedom to leave Vienna and move to London. The Nazis were rounding up and killing both Jews and psychoanalysts and Freud was a Jewish psychoanalyst.

Dr. Sigmund Freud arrives in Paris on his way to London, accompanied by Princess Marie Bonaparte and the American Ambassador In Paris William C. Bullitt. June 5, 1938

The Freud family relaxes in the garden at Princess Marie Bonaparte’s home in Saint-Cloud, France. June 5, 1938. Freud is lounging as he is deathly ill with oral cancer. He smoked 20 cigars a day.

Freud spent his first day of freedom in Marie’s gardens in Saint-Cloud before crossing the Channel to London, where he lived for his last 15 months. A few weeks later, Princess Bonaparte traveled to Vienna to discuss the fate of Freud’s four elderly sisters left behind. Her attempts to get them exit visas failed. All four of Freud’s sisters would perish in Nazi concentration camps.

Readers, for more on the European Royal Families here on Lisa’s History Room, click here. To read more about Prince Philip and Princess Alice, click here.

Sources: Eade, Philip. Prince Philip: The Turbulent Early Life of the Man Who Married Queen Elizabeth II. Vickers, Hugo. Alice: Princess Andrew of Greece. wikipedia and various Internet sites