Cicadas are due any day now to descend upon the whole state of Illinois. It’s a small mercy that the bugs are not locusts.

Early Kansas settlers had a rough time of it. For the first twenty years of Kansas settlement, homesteaders had to battle hot winds, drought, raids from native Americans, and hailstorms to save their crops. But the year 1874 promised to be different. “In the spring of 1874,” wrote Mrs. Everett Rorabaugh, “the farmers began their farming with high hopes, some breaking the sod for sod corn, others…sowing spring wheat, corn, and cane, and with plenty of rain everyone… [was] talking about the bumper crop they were going to have….”

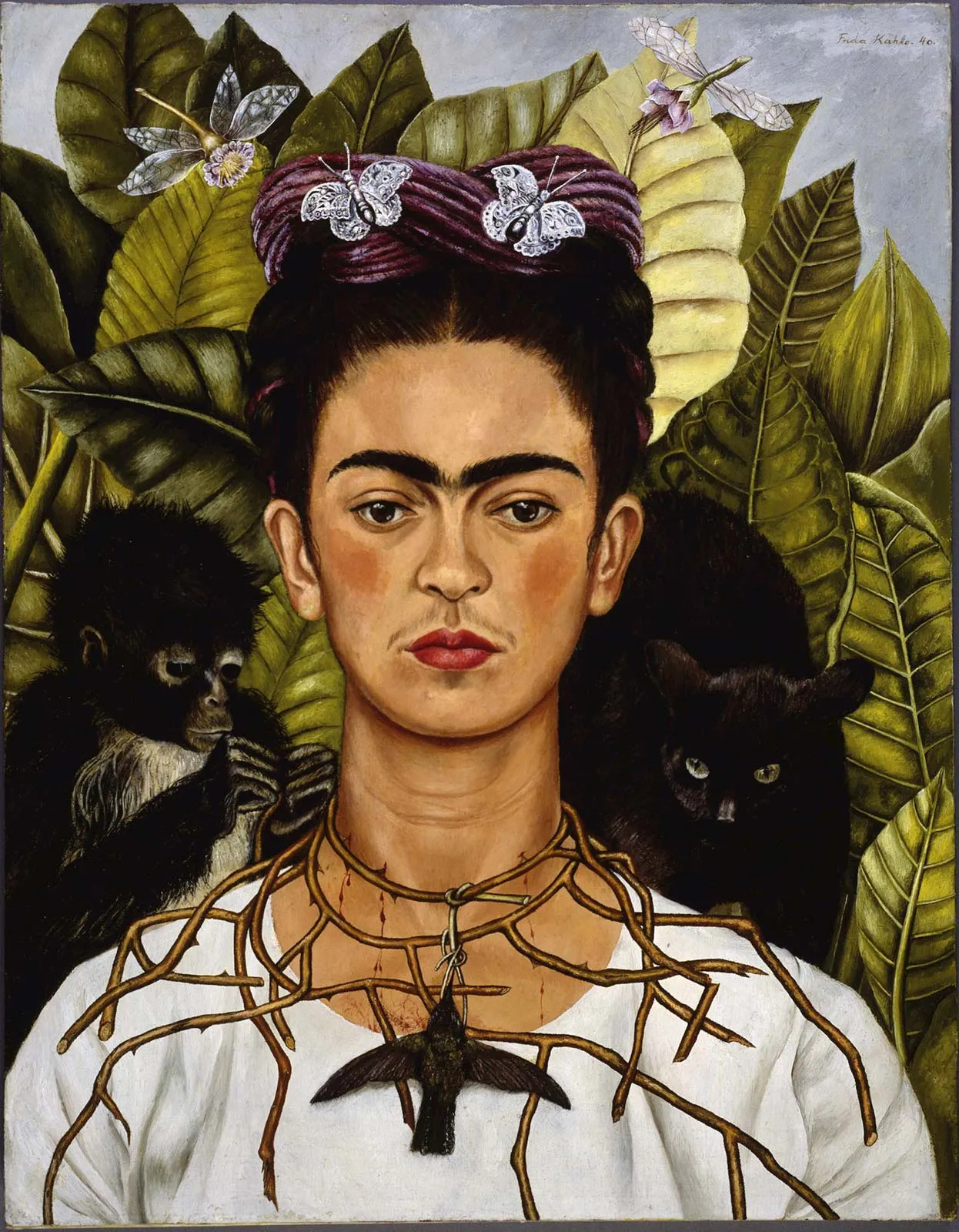

Rocky Mountain Locust, or grasshopper

But, by July, happy anticipation had turned to despair in when hordes of crop-eating grasshoppers descended upon Kansas. “August 1, 1874,” explained Mary Lyon, “is a day that will always be remembered…For several days there had been quite a few hoppers around, but this day, there was a haze in the air and the sun was veiled….They began, toward night, dropping to earth, and it seemed as if we were in a big snowstorm where the air was filled with enormous-sized flakes.” (1) The snowflake-like appearance was due to the whitish wings of the grasshopper, or Rocky Mountain locust.

The grasshoppers then dropped to the ground, crawling over the fields in a solid body, eating every green thing that was growing. Hillsides looked as if water were running down them the hoppers were so thick. They devastated the crops. When they had eaten the fields bare, leaving not a sprig of grass, they would pile up by fence posts and eat the bark off the posts.

Wishful Thinking

“They devoured every green thing but the prairie grass,” continued Mary Lyon. “They ate the leaves and young twigs off our young fruit trees, and seemed to relish the green peaches on the trees, but left the pit hanging….I thought to save some of my garden by covering it with gunny sacks, but the hoppers regarded that as a huge joke, and…ate their way through. The cabbage and lettuce disappeared the first afternoon….The garden was soon devoured.”

When the grasshoppers had cleared the land of vegetation, they ate the clothes drying on the clotheslines and curtains hanging in the windows. Adelheit Viets remembered the day the grasshoppers came to her farm. “The storm of grasshoppers came one Sunday. I remember that I was wearing a dress of white with a green stripe. The grasshoppers settled on me and ate up every bit of green stripe in that dress before anything could be done about it.” (1)

The insect hordes moved into barns and houses. Besides devouring food in cupboards, barrels, and bins, they attacked anything made of wood. They particularly craved sweaty things, eating the handles of pitchforks and the leather harnesses of horses.

In her book, On the Banks of Plum Creek, Laura Ingalls Wilder recalls the creepy feeling of the huge grasshoppers clinging to her clothes, writhing and squishing beneath her bare feet and the sound of “millions of jaws biting and chewing” as they destroyed her family’s fields in Minnesota. (2) The stench of the oily insects was hideous.

In her book, On the Banks of Plum Creek, Laura Ingalls Wilder recalls the creepy feeling of the huge grasshoppers clinging to her clothes, writhing and squishing beneath her bare feet and the sound of “millions of jaws biting and chewing” as they destroyed her family’s fields in Minnesota. (2) The stench of the oily insects was hideous.

When the grasshoppers were done, they rose with a humming that sounded like distant thunder, casting a shadow on the ground for a few seconds just as a cloud does when passing between you and the sun. Then they moved on, relentlessly in search of food. As they made their way cross-country, they landed on railroad tracks, making the tracks so slippery that the wheels of the train would only spin and an hour’s sweeping was needed to move their bodies out of the way.

Grasshoppers warming themselves on railroad tracks did stop trains but not exactly like this.

By September, the plague had moved eastward out of Kansas, leaving a state devastated by insects. The corn crop was nearly gone and the wheat crop substantially damaged. Gardens and fruit trees were totaled. Water in ponds, streams, and wells were polluted. Cows and chickens that had gorged on the grasshoppers became useless as food as did fish caught in streams. The meat smelled and tasted like grasshoppers. Chickens ate so many of the hoppers that egg yolks were red. Without a crop and livestock, pioneer farmers were destroyed.

Although Kansas governor Thomas A. Osborn pledged to provide relief to needy citizens, angry and discouraged pioneers fled Kansas by the hundreds in trains and by covered wagon. “In God we trusted; in Kansas we busted,” was a popular slogan painted on the sides of the wagons headed back east. For those who stayed behind, state governments and the U.S. Army distributed food rations to affected Kansans as wells as to others in the Dakota and Colorado territories, Minnesota, Iowa, and Nebraska, other places caught in the path of the grasshopper migration.

Families also needed clothes, many having only flour sacks to wear. So the government distributed old Civil War uniforms. For years after the grasshopper plagues, pioneer women and men could still be seen wearing these military uniforms while out working in their fields. (3)

Locust plagues long haunted American farmers, and they may do so again. In the 19th Century, black clouds of Rocky Mountain locusts swept across the plains almost every summer, leaving only stubble where crops once stood.

Locust plagues long haunted American farmers, and they may do so again. In the 19th Century, black clouds of Rocky Mountain locusts swept across the plains almost every summer, leaving only stubble where crops once stood.

Inset map: The 1874 swarm (shown in red) was the largest ever recorded: 1,800 miles long and 110 miles wide, it caused the equivalent of $650 million of damage. Other grasshopper species probably did not swarm, although they experienced major infestations in 1855, 1864, and 1866.

Large map: The U.S. Department of Agriculture releases a “Grass-

hopper Hazard Map” every year showing where infestations

are most likely to occur in the coming summer. In some areas,

grasshopper populations can reach densities of more than 200

per square yard. (Map by Matt Zang, 2003)

(1) Stratton, Joanna L. Pioneer Women: Voices From the Kansas Frontier. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1981)

(2) “Looking Back at the Days of the Locust,” New York Times, April 23, 2002.

(3) The ‘Hopper Plague of ’74,” True West, August 1990