"What I Saw in the Water or What the Water Gave Me," by Frida Kahlo, 1938. Frida painted herself in the bath. The right foot shows a bleeding sore between the deformed big toe and second toe. By the early 1940s, Frida would be in constant pain from her back and right foot. She would be forced to take to her bed and wear a series of body casts.

(First see “Frida Kahlo Had Childhood Polio Part 1.”)

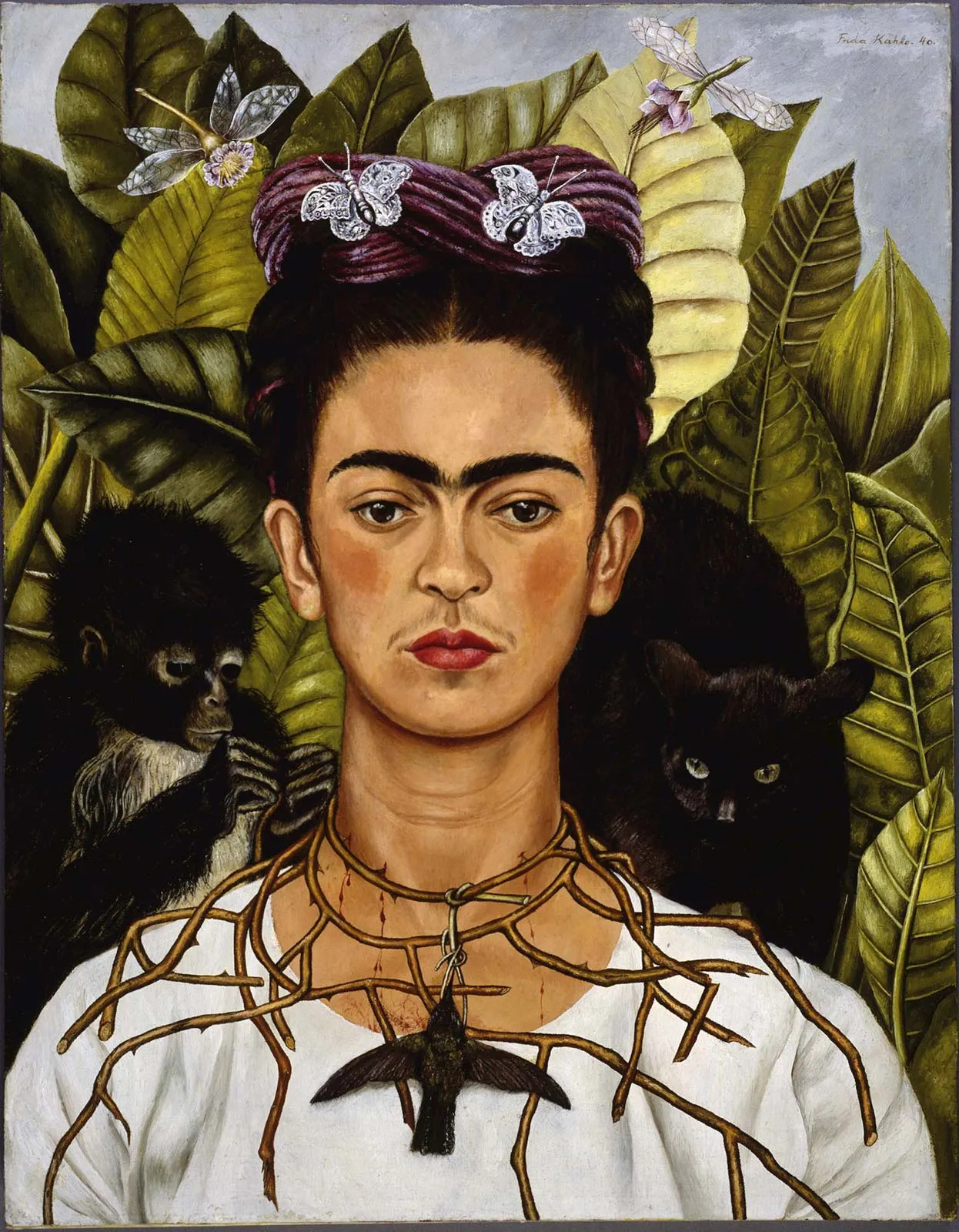

Frida Kahlo (1907-1954)

Mexican artist Frida Kahlo‘s childhood polio caused more than a slight deformity in her right leg. The decreased circulation to the limb caused her lifelong problems and pain.

From November 1-15, 1938, the first exhibition of Frida’s paintings was held at the avant-garde Julien Levy Gallery in New York City. At her opening, Frida looked spectacularly exotic in her Mexican costume, her starched bouffant skirts falling below her ankles.

"Frida on White Bench," photograph by Nickolas Muray, 1939

While the effect of her unusual outfit was striking and a perfect complement to her 25 paintings displayed in Mexican folkloric frames of metal, glass, and tin, Frida’s skirts played more than a decorative role. Frida explained:

“I must have full skirts and long, now that my sick leg is so ugly.”

The press was delighted with the paintings and Frida was the “flutter of the week in Manhattan.” During the course of the exhibition, Julien Levy wanted to show Frida the town. He took her bar-hopping in Harlem. He recalls:

“She didn’t jump to it, possibly because she was tired, and she couldn’t enjoy herself late at night. Bar-hopping is not easy to do if you are not light on your legs. She couldn’t overcome invalidism. After walking three blocks, her face would get drawn, and she’d begin to hang on your arm a little bit. If you kept walking, that would force her to say, ‘We must get a cab.'”

Frida’s right foot was the problem – again. She had developed warts on the sole of her foot. Of course, her spine ached. After her exhibit closed, she fell seriously ill. She saw a round of specialists, finally discovering Dr. David Glusker, who succeeded in closing the trophic ulcer that she had had on her foot for years.

Frida Kahlo in bed c.1950s

That was in 1938. Frida was to suffer pain for many more years, her degenerative spinal condition a result of the childhood polio and her streetcar accident in 1926. Some historians have suggested that Frida may have suffered from yet a third problem. They think that Frida could have been born with spina bifida, which further complicated her spine and leg issues.

Over the course of her lifetime, Frida would endure over 30 surgeries, multiple hospitalizations, and countless months of bedrest. Frida managed the constant pain with copious amounts of brandy and pills.

In 1953, gangrene set into her right foot and her leg had to be amputated below the knee. Frida was devastated.

After the 1953 amputation of her right leg below the knee because of her gangrenous right foot, Frida drew this image of her feet in her diary. She tried to make light of the loss, writing the poignant phrase, "Pies para que los quiero, si tengo alas pa' volar?" (Feet, why do I want them if I have wings to fly?)

The next year, Frida was dead from a morphine overdose, self-administered, probably a suicide.

READERS: For more posts on Frida Kahlo, click here.

Read Full Post »