Readers: Although Julia Ward Howe is not mentioned in my soon-to-be-published history, When People Were Things, her husband is. Although Julia’s Civil War activism is not included in the book, I want to give you a snippet view here.

Julia Ward Howe (1819-1910)

Portrait of Julia Ward Howe, by John Elliott, ca. 1925. National Portrait Gallery/Wikimedia Commons

In 1843, red-haired New York heiress Julia Ward married Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe who had founded the Perkins School for the Blind. She was 24; he was 42. Julia gave birth to their first child while they honeymooned in Europe. She called her husband, “Chev.” They had six children and lived in Boston and Rhode Island. Theirs was not a happy union. Chev disapproved of Julia’s writing and did all he could to thwart it. In 1853, she published her first volume of poetry, Passion-Flowers, anonymously and without her husband’s knowledge. She continued to publish works that often critiqued women’s roles in marriages and society and caused controversy. Her husband was troubled by her writing as it often contained pointed references to her unhappy and stultifying marriage. He did not approve of women having a career outside the home.

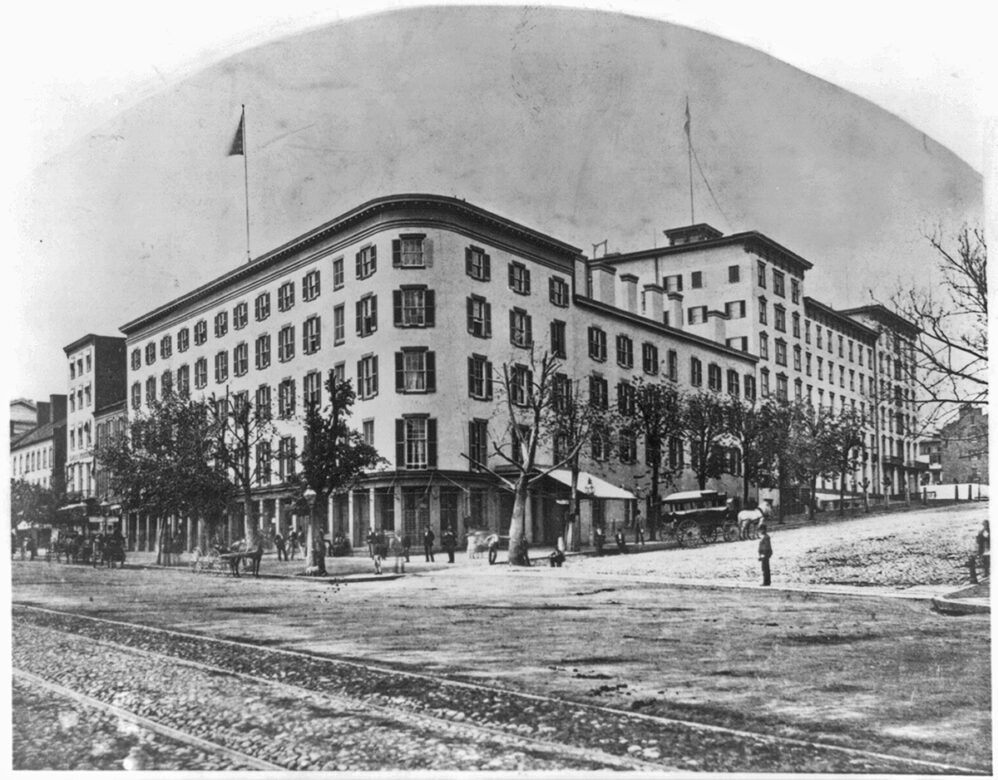

In November 1861, the first year of Abraham Lincoln’s presidency and while the Civil War was raging, Julia and Chev traveled to Washington and met Abraham Lincoln, who, Julia wrote, “was laboring…under a terrible pressure of doubt and anxiety.” Dr. Howe was on the board of the U.S. Sanitary Commission that supported wounded and sick soldiers; during his stay, he would meet with the USSC founder Dorothea Dix. The Howes lodged at Willard’s Hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue.

The Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C., during the Civil War Years, Library of Congress

From their room, Julia saw a billboard advertisement for “an agency for embalming and forwarding the bodies of those who had fallen in the fight or who had perished by fever.” This image stayed with her.

On a visit to the huge military camps stationed in the national capital, she heard soldiers singing the song, “John Brown’ Body,” originally about a Scotsman but had taken on new meaning in reference to the insurrectionist at Harper’s Ferry. New verses were often being added:

Old John Brown’s body is a-mouldering in the dust,

Old John Brown’s rifle is red with blood-spots turned to rust,

Old John Brown’s pike has made its last, unflinching thrust,

His soul is marching on!

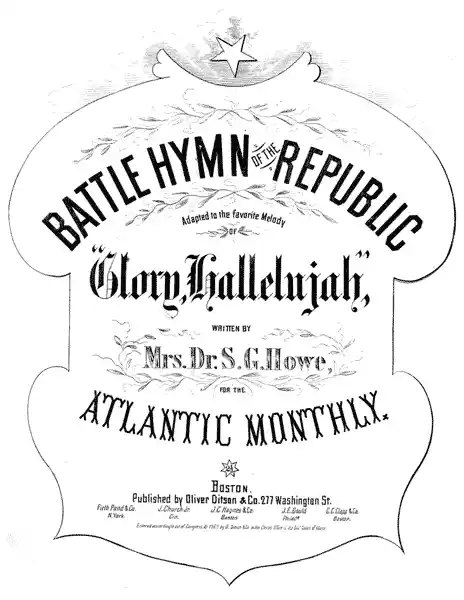

A friend urged Julia to write “some good words for that stirring tune.” That evening, she tried, but the words did not come to her. The next morning at the graying first light, she woke up in her bed at Willard’s and the words of the poem began to flow. She jumped up, grabbed paper and an old stump of a pencil, and scrawled down the words without even looking down at the paper, then fell back to sleep. This is how “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” was born, which she sold to the Atlantic Monthly for $4 in February. Her version links the Union cause to God’s vengeance at the Day of Judgment.

Here are some verses from the first published version:

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord,

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored;

He hath loosed the fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword:

His truth is marching on.

(Chorus)

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

His truth is marching on.

I have seen Him in the watch-fires of a hundred circling camps,

They have builded Him an altar in the evening dews and damps;

I can read His righteous sentence by the dim and flaring lamps:

His day is marching on.

(Chorus)

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

His truth is marching on.

Before long, the song caught on and became the favorite of the Union troops and its unofficial wartime anthem. Julia Ward Howe became somewhat of a celebrity and became a suffragist.