Readers: For a time, I will be blogging about people who appear in my soon-to-be-published nonfiction history, When People Were Things: Harriet Beecher Stowe, Abraham Lincoln, and the Emancipation Proclamation. Today, General McClellan, Abraham Lincoln, and two of Lincoln’s cabinet secretaries are featured. I promise not to include book spoilers.

Lincoln told a colleague, “I wish McClellan would go at the enemy with something – I don’t care what. General McClellan is a pleasant and scholarly gentleman. He is an admirable engineer, but he seems to have a special talent for a stationary engine.”

It is spring 1862, the second year of the American Civil War. Although General George McClellan, leader of the Union Army of the Potomac, had finally moved his troops out of his Washington, D.C., camp, he had stalled out on the Virginia Peninsula. Procrastination was his custom and he had endless excuses to offer for his delay tactics. He heaped blame on President Abraham Lincoln for not supplying him with enough troops as McClellan falsely believed he was outnumbered by the rebels. Lincoln was frustrated with McClellan’s chronic inaction, as McClellan delayed moving his troops toward the Confederate capital of Richmond and attacking and bringing the war to a swift end.

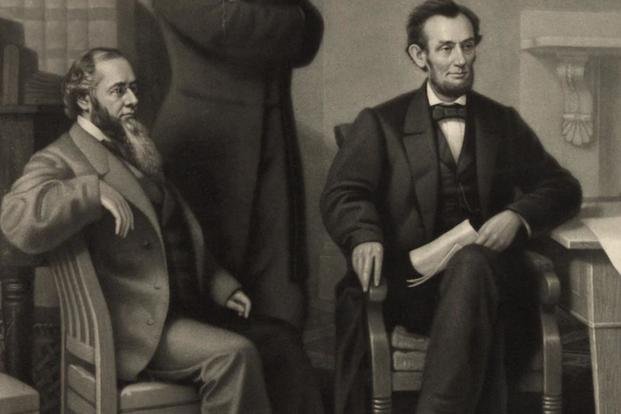

At left, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton sits with President Abraham Lincoln (Library of Congress)

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton suggested that President Lincoln take a trip to the Virginia Peninsula, to Fort Monroe, to prod General McClellan to act. On the evening of May 5, 1862, Lincoln, Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, and Stanton, accompanied by General Egbert Viele, boarded the new Treasury Department cutter, the Miami, and began the twenty-seven-hour journey, sailing down the Potomac, and into the Chesapeake Bay.

The next day, the bay water was so choppy that the noontime meal was fatally disrupted. Lincoln was too miserable to eat, did not stay at the table, and stretched himself out elsewhere. The others in the party tried to enjoy the meal elaborately planned by the host, Chase, and served by his butler, but Chase wrote his daughter, Nettie:

“[T]he plates slipped this way and that, the glasses tumbled over and rolled about, and the whole table seemed as topsy-turvy as if some spiritualist were operating upon it.”

They reached Fort Monroe at about nine o’clock that night. Stanton sent a telegram to McClellan who was only a few miles away and suggested he join them for a conference. McClellan declined. Stanton was not a military man; he like Lincoln, was a lawyer. McClellan had no respect for either of them. McClellan regularly disregarded them.

Lincoln quickly turned his attention to another matter of concern.

Union forces at Fort Monroe occupied the Northern shore of Hampton Roads, a body of water that serves as a wide channel which connects the Chesapeake Bay to three rivers. On the Southern shore, Confederates still held Norfolk and the Navy Yard. The powerful ironclad nine-gun Merrimac (renamed by the Confederates, the Virginia) was docked at the Navy Yard.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/css-virginia-large-56a61c395f9b58b7d0dff708.jpg)

CSS Virginia (the Union Merrimac or Merrimack) was the first ironclad warship constructed by the Confederate States Navy during the American Civil War. It was built from the remains of the former steam frigate the USS Merrimack.

Back in March 1862, in a span of five hours, this former Union ship had sunk, captured, and incapacitated five Union vessels in what was known as the Battle of Hampton Roads or the Battle between the ironclads, the Monitor and the Merrimac(k).

March 1862. The Battle of Hampton Roads: Print shows a battle scene between the ironclads Monitor and Merrimac just offshore, also shows a Union ship sinking and rescue boats being put to sea from shore, as well as a Union artillery bunker, Union soldiers and officers, and some rescued sailors. The 3-hour battle between the two ironclads was indecisive. (Library of Congress)

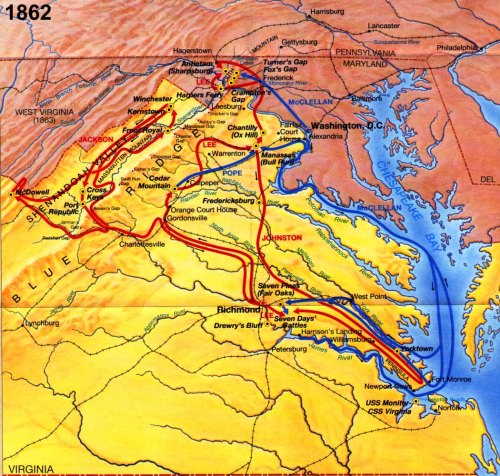

Lincoln feared that the Merrimac would one day sail up the Potomac and attack Washington, the capital of the Union. Lincoln and his advisors pored over maps of the area. The men could not understand why McClellan had not ordered an attack on Norfolk and captured it. Norfolk was wide open. Confederates had left both the city and the Navy Yard vulnerable. Lincoln and his mini-war cabinet planned an assault on that key port to be made by General Wool’s forces.

Although this map shows a lot of info, you can pick out Fort Monroe, Washington, D.C., the Potomac River, Richmond, and Norfolk, Va. The Confederate and Union capitals were only about 100 miles apart.

On the afternoon of May 7, at Lincoln’s suggestion, several Union warships began the shelling of the rebel guns at Sewell’s Point near Norfolk. Upon learning that the rebels were abandoning Norfolk, Lincoln decided to plan its capture.

Lincoln, Chase, and Stanton surveyed the shoreline seeking a good place for the troops to land. Lincoln went ashore in a rowboat, walked around on enemy soil under a full moon, putting himself in danger of being fired upon, and then returned to the Miami. Chase was antsy for an immediate attack. He was worried that McClellan might show up and delay it!

When the convoys landed on the sandy beach the next night (at the landing Chase and Wool had selected), they found that the rebels had evacuated the city and scuttled the Merrimac. The city authorities formally surrendered the city to the Union forces and Wool appointed Viele as the city’s military governor.

In a letter to his daughter, Chase praised the President for the capture of the strategic port city and the vanquishing of the Merrimac. The egoistic McClellan, however, wrote falsely to his wife, “Norfolk is in our possession, the result of my movements.”

Readers: Later this spring my new book, WHEN PEOPLE WERE THINGS: HARRIET BEECHER STOWE, ABRAHAM LINCOLN, AND THE EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION, will be published. Please read it.

Merrick Garland!

I used to live down the street from the hotel McClellan was staying in when he finally got the telegram from Lincoln firing him.

Great blog.

LikeLike

Tell me where. Thanks for reading and complimenting.

LikeLike

“Warren Green” in Warrenton, VA.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warrenton,_Virginia?wprov=sfti1

LikeLike