Readers: I will be blogging about people who appear in my upcoming book, When People Were Things, but include here different stories than are in the book.

The American Civil War (1861-1865)

Following the Union defeat at Manassas (1st Bull Run), Virginia, in July 1861 to the Southern Confederate forces, President Abraham Lincoln understood that the disorder of the newly-formed troops had contributed to the debacle. Lincoln wanted the Union army to be “constantly drilled, disciplined, and instructed.”(1) He sent a telegram to George McClellan, 34,—a West Point graduate, a distinguished veteran of the Mexican-American War, and fresh from having defeated a guerilla band in West Virginia, the only Union victory to date— to come at once to Washington City and take charge of the Army of the Potomac. As he traveled by special train to the capital, enthusiastic crowds heralded his passage along the way. The capture of Washington by rebel forces seemed imminent. Northern delusions of an easy victory vanished.

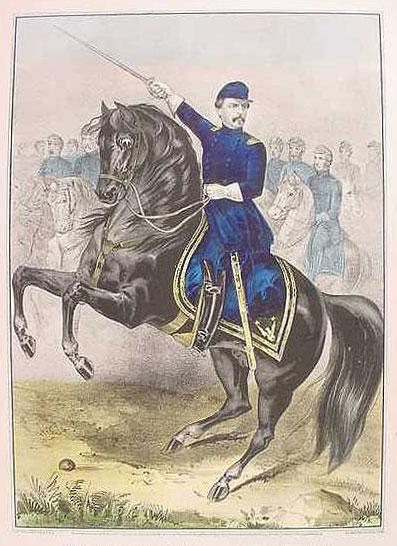

Major. Genl. George B. McClellan Lithograph, Currier & Ives, 1862.

Within days of McClellan’s arrival, Washington achieved a “more martial look.” (2) McClellan had managed to instill more confidence in the demoralized troops who had retreated in disarray from Bull Run. The soldiers adored “Little Mac.” Drunken soldiers no longer loitered in bars and streets. McClellan wrote to his wife,

I find myself in a new and strange position here: President, cabinet, Gen. Scott, and all deferring to me….I seem to have become the power of the land. I almost think that were I to win some small success now, I could become Dictator…. (3)

Major General George McClellan and his Wife, Ellen Mary Marcy (Nelly), ca. 1860-65.

McClellan disagreed with General Winfield Scott who wanted to attack the enemy in different theaters of war. McClellan believed that he could put an end to the war by concentrated overwhelming forces on Virginia. Summer gave way to fall. Indeed, McClellan had turned the recruits into soldiers and created a powerful army.

In the early months of the war, women worked as laundresses and cooks while the volunteer soldiers drilled and constructed the Defenses of Washington. TITLE: “Washington, District of Columbia. Tent life of the 31st Penn. Inf. (later, 82d Penn. Inf.) at Queen’s farm, vicinity of Fort Bunker Hill.” Library of Congress

While McClellan conducted magnificent reviews in the capital of more than fifty thousand troops marching in straight and orderly columns, and boasted great military plans, he did not seem willing to lead his army anywhere. He was weighed down by fear while the Confederates were bolstered by optimism from their Manassas victory. Congress and Washingtonians grew restless with McClellan’s delay in avenging Bull Run.

This sketch shows a panoramic view of the Grand Review of the Union Army. The illustration appeared in the 7 December 1861 issue of Harper’s Weekly, which claimed that the artist sketched the review while perched on the roof of a barn.

Accustomed to success and thus fearful of failure, McClellan did not want to move; his constant complaint was that he did not have enough troops. Allan Pinkerton, his secret operative, fed his insecurity. Pinkerton provided “Little Mac” with the faulty intelligence that the enemy had at least 150,000 men within striking distance of the capital. McClellan said he would not move until he had 270,000 men of his own. In truth, in October 1861, McClellan had 120,000 men while rebels in and near Manassas had only 45,000. (4) In September, when Confederate pickets withdrew from their position a few miles southwest of Washington on Munson’s Hill, Federal troops discovered that the great cannon they had believed was trained on the capital was nothing but a giant log shaped and painted to resemble a cannon. This “Quaker gun” embarrassed McClellan. Calls for his dismissal intensified.

Confederate “Quaker Guns,” Manassas, Va., 1862

(1) Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals, 373.

(2) Ibid, 378.

(3) Ward, Geoffrey. The Civil War, An Illustrated History, p. 75

(4) MacPherson, James. Battle Cry of Freedom, 360-361.

Readers: Please check this space for when my new book, When People Were Things, is available. Please read it.