Princess Margaret of Britain loved to dress up. Here she is at age 34 at a Georgian ball at Mansion House, 1964. A Georgian-themed affair is a throwback to the days of French Queen Marie Antoinette: heavy on white wigs and powdered faces. Getty Images.

From a very young age, Princess Margaret of Britain (1930-2001) loved to dress up in costumes, act, sing, and dance—and she had real talent. At the age of nine months, for example, she had astounded her grandmother with her gift for music, by humming the waltz from “The Merry Widow.”

Her enchantment with the magical world of music, dance, and theatre was cultivated early, in large part, by her childhood attendance at the annual Christmas pantomimes in London prior to the outbreak of WWII in 1939. Her parents, titled at her birth as the Duke and Duchess of York and then, after 1936, titled as King George VI and Queen Elizabeth of Great Britain, would take Margaret and her older sister, Princess Elizabeth (later Queen Elizabeth II), to the rollicking shows every winter holiday.

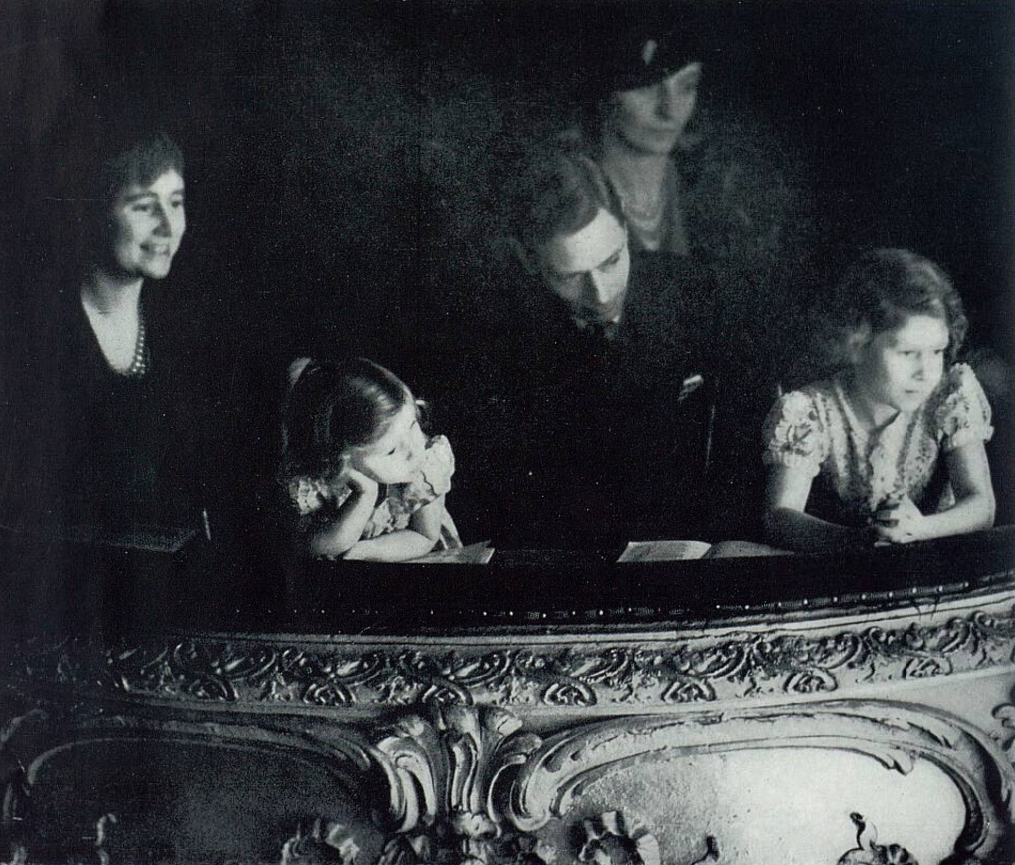

In the Duchess’s box at the Lyceum Theatre, London, the Duke and Duchess of York and their daughters, Princesses Margaret (l.), 4, and Elizabeth, 8, enjoy the Christmas pantomime, “Dick Whittington,” in which Dick promises that his cat will rid the realm of rats. February 1935.

The 1934-35 playbill for the pantomime enjoyed by Princesses Margaret and Elizabeth and their parents in February 1935. Cast: Dick Henderson, George Jackley, Naughton & Gold, Molly Vyvyan, Elsie Prince, Audrey Acland and Eric Brock.

British pantomimes are a peculiar bit of theatre. The name, “pantomime,” is misleading, as the word “mime” evokes an image of the silent French mime Marcel Marceau alone on stage, in white face makeup, leaning into an invisible wind, battling to open an invisible umbrella, a sublime and subtle entertainment. A British pantomime, on the other hand, is pure camp—loud, boisterous, ridiculous and, sometimes, a little naughty. This musical comedy stage production is loosely based on a favorite children’s story such as “Cinderella,” “Aladdin,” or “Puss and Boots” but with dramatically-altered plot lines and a motley crew of characters. An assortment of costumed performers dance and sing, belting out tunes familiar to the audience but with new and absurd lyrics designed to draw a lot of laughs. Oddly, although pantos are Christmas entertainment, there are no references to Christmas in the scripts.

The panto audience is encouraged to participate. They shout out to the actors, “Look out, he’s behind you!” they hiss at the villain, they cry, “Awwwww” to the poor victims.

An example of audience participation in the pantomime version of “Sleeping Beauty”:

Wicked Queen – “I am the fairest of them all”

Audience – “Oh no you’re not!”

Queen – “Oh yes I am!”

Audience – “Oh no you’re not!”

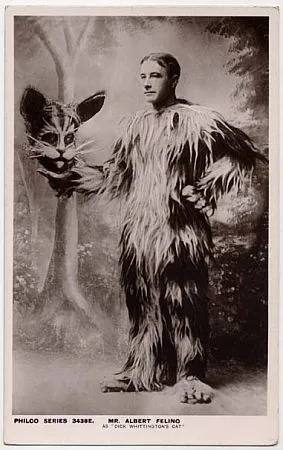

There are sing-a-longs. Animals are usually humans in costume like the Pantomime Horse, with one person in the front and another pulling up the rear.

Famous English animal impersonator Albert Felino in the role of the cat in “Dick Whittington.” Theatre Royal, Edinburgh, Christmas (photo: unknown, England or Scotland, probably 1908; postcard, The Philco Publishing Co, London, Philco Series 3438E)

Think of a British pantomime as a cross between “Sleeping Beauty” and a vaudeville show with slapstick humor, bawdy jokes, gender-swapping, special effects like magical transformation scenes as in “Cinderella,” and capped by celebrity appearances.

With all their color, excitement, music, costumes, bright lights, gags, and laughter, these once-a-year pantomimes made a lasting impression on the young Princess Margaret. This special time with her loving family—before the bombs began to fall—was pure joy—and formed the foundation upon which she crafted her own talents as an amateur actress, mimic, and singer and developed a lifelong taste for theater, dance, and music.

Margaret’s childhood nanny from 1932-1948, Marion “Crawfie” Crawford, recalled:

In those happy pre-war days, theatre managers always had a large box of chocolates in the royal box. But the little girls’ great ambition was to sit in the stalls or the dress circle. They had to hang over the side of the royal box, to see properly. I can still see the Duke anxiously seizing his daughters’ petticoats, afraid they would fall over altogether in their immense enthusiasm.

The children looked forward to these pantomimes for the remaining eleven months of the year. Margaret, as soon as she could talk at all, would reenact most of the parts….”

In 1936, the Duke of York became King George VI of Great Britain and his wife became Queen Elizabeth (who, in 1952, would be styled as Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother or the Queen Mum). The young family, whom the King dubbed affectionately as “Us Four,” left their stately home at 145 Piccadilly and moved three miles, as the crow flies, across London to Buckingham Palace.

“Us Four.” The British Royal Family, 1937. Getty Images.

Four years later, in May 1939, England was at war with Nazi Germany. It was not safe for children in London during the bombing so Margaret and Elizabeth moved to Windsor Castle, a medieval fortress with thick walls, just 21 miles west of London. Margaret would live at Windsor until the war’s end in May 1945, from the age of nine years old to fifteen. The girls roomed in the “nursery” in the Augusta Tower.

an aerial view of Windsor Castle, over 900 years old (2020), a working palace and a setting for a fairy tale. Photo credit: Organic Society.

For the most part, the King and Queen stayed in London at Buckingham Palace, visiting the girls on Saturdays and Sundays. By staying in town during the Blitz, the royal couple put their lives in great jeopardy as the Palace was bombed nine times by the German Luftwaffe. In September 1940, they were almost killed when the Nazis dropped bombs on the Palace Chapel, destroying it.

At about 11 a.m. on 13 September 1940, a week after the start of the London Blitz, a German bomber ducked under the clouds, flew deliberately low across the capital [London] and dropped five high explosive bombs on Buckingham Palace. George VI and his wife, Elizabeth, were just taking tea. At the precise moment that they heard what she described as the “unmistakable whirr-whirr” of the plane, the queen was battling to take an eyelash out of his eye and they rushed out into the corridor to avoid the blast. Two bombs fell in the palace’s inner quadrangle a few yards from where the couple had been sitting, a third destroyed the chapel and the remainder caused deep craters at the front of the building. 1

Windsor Castle was near enough to the repeated shelling of London for the sisters to feel the walls of the great Windsor Castle shake and to hear the “whistle and scream” of the bombs as they fell from the skies. Although we know now that the Germans never did succeed in invading England according to their plan, during the war, expectation of an imminent invasion was an everyday worry for Britons. Windsor Castle was reinforced by barbed wire which Margaret thought rather futile, saying in a later interview that it wasn’t very capable of keeping the Germans out. Rather, it kept her IN.

(l. to r.) Princess Margaret and Princess Elizabeth on the grounds of Royal Lodge, Windsor, 1940. Getty Images

Windsor was a giant beehive of thirteen acres with 1,000 rooms just for the royal family. Over 350 servants lived and worked there. In addition, officials, courtiers, guardsmen, soldiers on leave, soldiers convalescing, boys from Eton buzzed in and about. Margaret remarked, “I was brought up among men,” which is no understatement. So, although life was serious: daytime lessons for the girls in academics, dance, piano, and language, and, as part of the war effort, bandage-rolling, sock-knitting, and tinfoil collection was obligatory, and Windsor was dark, with the sparkling chandeliers taken down, the state apartments cloaked in sheets, windows blacked out, and with only log fires in the sitting rooms for warmth, there were still lighthearted times for those forced to be there. The girls sang in a Madrigal Society with the soldiers and boys from Eton. There were occasional balls. The girls loved to dance and the King loved to waltz, in particular. The sisters served tea to the soldiers and, afterwards, played guessing games and charades. Crawfie and the two girls played one-man charades in which each one took a turn imitating someone they knew and the others guessed. Crawfie said that the sisters—in particular, Margaret,

had considerable talent for acting…There was never any doubt about Margaret’s efforts! They were unmistakable. She kept us in fits of laughter with this first manifestation of a talent that was one day to amuse a much larger circle…Lilibet [Elizabeth] was always a more serious child….

After dinner at night with their parents and their parents’ guests, they played more charades until midnight. (The Queen Mother would later become incensed when Crawfie wrote a book—the first of many nanny diaries to come—about her time in the royal household. Crawfie wanted to include in her tell-all about a night of charades when the Duchess of Kent imitated pulling a lavatory chain—flushing a toilet—as a clue to the phrase, “royal flush.” The Queen Mother insisted that Crawfie had violated the terms of her employment. Crawfie edited out this story, as per the Queen Mother’s wishes, but from then on, she was persona non grata.)

It was at Windsor that Margaret’s talent for acting found both a wider audience and a larger appreciation. Each Christmas from 1941 until 1945, the two princesses took the leading roles in locally-produced pantomimes for the benefit of the Royal Household Concert Wool Fund. The full-scale productions were staged in the Waterloo Chamber of the Castle. Although Princess Elizabeth did a good job at acting and tap-dancing for more than five hundred, including townspeople and soldiers, it was Princess Margaret, with her sparkle and spunk, that stole the show. Margaret’s admirers remarked on her skill in impersonating cockneys or Southern belles or shy town clerks. She had a knack for mimicking regional accents and dialects.

This “gift of fun-poking—and very clever fun-poking” as Crawfie termed it, would, in her adult life, when she had grown old, alcoholic, and sickly, be used by Margaret to craft remarks that cut people to the quick, alienating even those who loved her, and for which she would become notorious, reviled, and ostracized. Her sardonic quips were repeated, becoming legendary. Given that she was royal, she was unstoppable, as no one dared correct a woman to whom one curtseys and bows.

1941: Princess Elizabeth discusses the pantomime with her mother, Queen Elizabeth of England, while her sister, Princess Margaret, looks on. AP photo.

Sources:

Crawford, Marion. The Little Princesses: The Story of the Queen’s Childhood by Her Nanny, Marion Crawford. (1950)

multiple bios of QEII, Princess Margaret

Readers, for more on Marie Antoinette, click here. For more on Princess Margaret, click here. For more on the British Royal Family, click here.