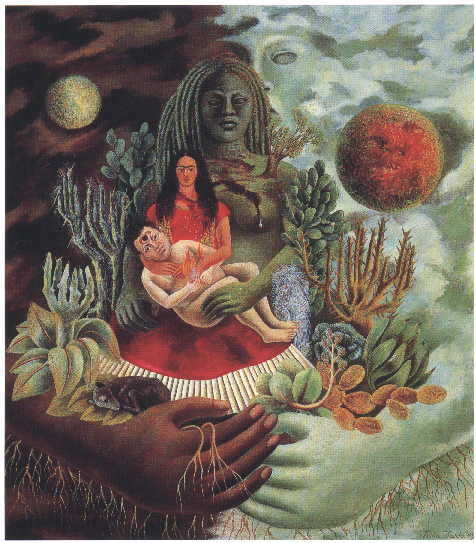

“The Bus,” by Frida Kahlo (1929). Frida painted her recollection of the last moments aboard the bus before the terrible accident that robbed her of her health. She is pictured on the far right. Notice that she is not dressed in traditional Mexican costume. She adopts that exotic look later, after her 1929 marriage to flamboyant Mexican muralist Diego Rivera.

Mexican artist Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) once said that she suffered two bad accidents in her life. The first one occurred on September 17, 1925. It would transform her life forever. Frida was only 18.

It was a gray day. A light rain had just fallen. After spending the afternoon wandering among the street stalls of downtown Mexico City, Frida and her boyfriend Alex Gómez Arias caught a bus that would take them home to Coyoacán. The new bus was brightly painted with two benches along the sides. It was nearly full but Alex and Frida found seats together near the back. The bus driver sped off to cross the busy streets on his way out of town.

As the bus driver began to turn onto Calzada de Tlapan, a street trolley approached. The bus driver rashly tried to pass in front of the turning streetcar. He didn’t make it. Alex remembers the point of impact:

The electric train [streetcar] with two cars approached the bus slowly. It hit the bus in the middle. Slowly the train pushed the bus. The bus had a strange elasticity. It bent more and more, but for a time it did not break. It was a bus with long benches on either side. I remember that at one moment my knees touched the knees of the person sitting opposite me. I was sitting next to Frida. When the bus reached its maximal flexibility it burst into a thousand pieces, and the train kept moving. It ran over many people.

I remained under the train. Not Frida. But among the iron rods of the train, the handrail broke and went through Frida from one side to the other at the level of the pelvis.”

Frida said that the “handrail pierced me the way a sword pierces a bull.” Alex continues:

When I was able to stand up, I got out from under the train. I had no lesions, only contusions. Naturally the first thing that I did was to look for Frida.

Something strange had happened. Frida was totally nude. The collision had unfastened her clothes. Someone in the bus, probably a house painter, had been carrying a packet of powdered gold. This package broke, and the gold fell all over the bleeding body of Frida. When people saw her, they cried, ‘La bailarina, la bailarina!’ With the gold on her red, bloody body, they thought she was a dancer.

I picked her up….and then I noticed with horror that Frida had a piece of iron in her body. A man said, ‘We have to take it out!’ He put his knee on Frida’s body and said, ‘Let’s take it out.’ When he pulled it out, Frida screamed so loud that when the ambulance from the Red Cross arrived, her screaming was louder than the siren. Before the ambulance came, I picked up Frida and put her in the display window of a billiard room. I took off my coat and put it over her. I thought she was going to die. Two or three people did die at the scene….others died later.”

Frida’s condition was so grave doctors didn’t believe they could save her. They thought she would die on the operating table. Her spinal column was broken in three places in the lumbar region. Her collarbone was broken and her third and fourth ribs. Her right leg had eleven fractures and her right foot was dislocated and crushed. Her left shoulder was out of joint, her pelvis broken in three places. The steel handrail produced a deep abdominal wound, entering through the left hip and exiting through the genitals. She convalesced for two years though she would never fully recover.

It was while she was confined to bed that Frida began to paint, using a small lap easel her mother bought for her. Frida had a mirror hung overhead in the canopy of her bed so she could use her reflection as a beginning subject for portraits.

Next: Frida Kahlo: The Other Accident