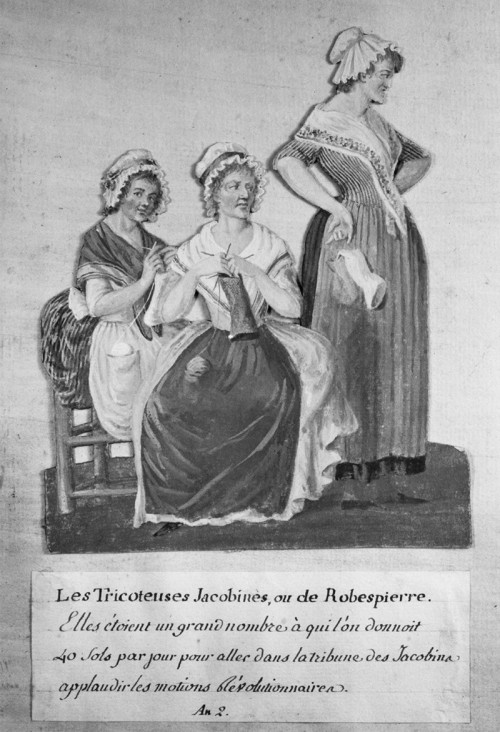

The knitting women of the French Revolution. Pierre-Etienne Lesueur’s Les Tricoteuses Jacobines, 1793. (Wikimedia)

At the start of the French Revolution, the market women of Paris, hungry for bread, marched by the thousands to Versailles to confront King Louis XVI and his government over rising food prices and food shortages. Surprising everyone, their demands were met and, in addition, they convinced the royal family—including Queen Marie Antoinette—to relocate to the French capital city. Working class women had never before demonstrated such political clout. These women were hailed as sisters of the Revolution and were invited to important political events. These “mothers of the revolution,” or “bonnes citoyennes,” became overnight heroines for the cause of liberty. They came to be known as the knitting women, or tricoteuses (pronounced trick uh TUZZ).

Over time, though, the tricoteuses grew swollen with power and inflamed by the fury of the Revolution. They became rowdy and blood-thirsty, harassing aristocrats in the street, insulting them and urging the radical sans-culottes, or lower class militants, to carry out dreadful atrocities against them. The tricoteuses were like the Greek furies that punished culprits they thought were guilty by hounding them relentlessly.

The French Revolution lasted ten years. Before it was over, it descended into an all-out savage bloodbath known as the Reign of Terror (1793-1794). In just that one year period, 17,000 French people were executed. Shown here are rabid revolutionaries parading shorn heads on pikes. (wikipedia)

The behavior of the tricoteuses became so dangerous that they became a liability to the more authoritarian revolutionary government. On May 21, 1793, the women were banished from government proceedings. Later that week, they were forbidden from forming any political assembly. The tricoteuses were reduced to hanging around the guillotine.

The Tricoteuses of the Guillotine on the Steps of the Church of Saint-Roch, 16th October 1793. Henri Baron (Pinterest)

They were the ghoulish women who sat and knitted while the public executions took place during the French Revolution (1789-1799). Many knitted liberty caps, their sharp needles clackety-clacking, while head after head fell beneath the blade and into the basket.

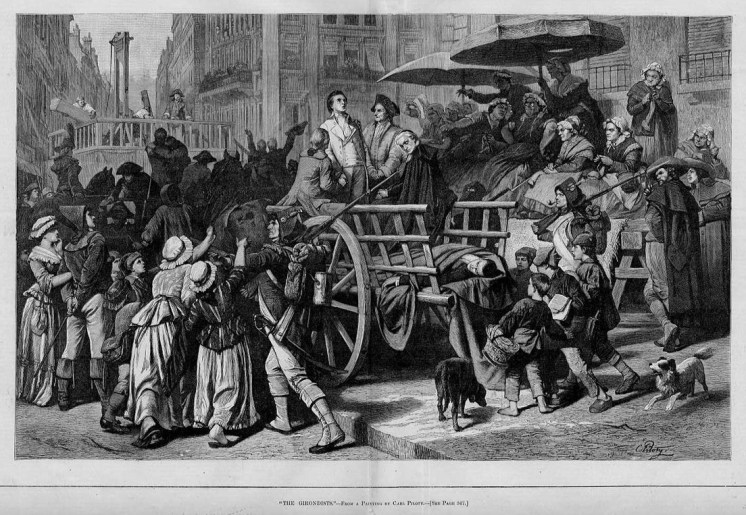

A French man is transported to the guillotine to be beheaded. In the upper right hand corner of the picture, the tricoteuses jeer, bellow, hurl accusations at him, and call for his immediate execution. Etching from Harper’s Weekly, August 1881, from a painting by Carl Piloty, “The Girondists.”

Charles Dickens popularized the tricoteuses in The Tale of Two Cities (1859), set in London and Paris before and during the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror. One of the main villains of the novel is Madame Defarge, a tricoteuse, a French Revolution fanatic obsessed with the extermination of real and imagined enemies of the Revolution. She knits and her knitting secretly encodes the names of people to be killed.

The tricoteuse Madame DeFarge (r.) confronts Miss Pross over the whereabouts of the Evrémonde family. Scene from the novel, A Tale of Two Cities, by Charles Dickens, 1859. Image by Fred Barnard, 1870s (wikipedia)

**Read more about the French Revolution and Marie Antoinette here. Sources: wiki: "Reign of Terror" wiki: "tricoteuse" The Telegraph: "QI: How Knitting was Used as Code in WW2" Timeline: "Horror Spectators: The Lady Revolutionaries who Calmly Knit During Executions" Geri Walton: "Tricoteuses: Knitting Women of the Guillotine"

The pouf was halfway between a hairstyle and a hat. The thickly-powdered hair was teased away from the face then arranged high on the head on a wire scaffolding resembling a cone-shaped garden topiary. Next, the hairdresser added and intertwined false curls—curly, wavy, crimped— sometimes made of horsehair, diamond jewelry, ropes of pearls, yards of gauze, lace, and ribbon, pompoms, ostrich and peacock feathers, bows, rosettes, butterflies, figurines, and props. With such ornamentation, the stylist then set about to create a miniature still-life upon this rickety foundation. The theme of the elaborate, yard-high headdress could be a sentiment, a commemoration of an event, or an expression of a political opinion. The creativity was inexhaustible.

The pouf was halfway between a hairstyle and a hat. The thickly-powdered hair was teased away from the face then arranged high on the head on a wire scaffolding resembling a cone-shaped garden topiary. Next, the hairdresser added and intertwined false curls—curly, wavy, crimped— sometimes made of horsehair, diamond jewelry, ropes of pearls, yards of gauze, lace, and ribbon, pompoms, ostrich and peacock feathers, bows, rosettes, butterflies, figurines, and props. With such ornamentation, the stylist then set about to create a miniature still-life upon this rickety foundation. The theme of the elaborate, yard-high headdress could be a sentiment, a commemoration of an event, or an expression of a political opinion. The creativity was inexhaustible.