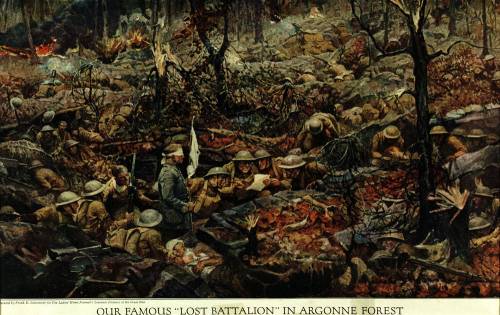

World War I, France

On October 1, 1918, about 550 soldiers of the U.S. 77th Division found themselves surrounded by Germans in the Argonne Forest. Major Charles Whittlesey was their leader. He was just following orders, to push forward at all costs, push the enemy further toward the border and out of the country. Instead, after traipsing through thick brush and tangled wires, old abandoned German headquarters, and dead bodies, they were behind enemy lines, trapped in the Charlevaux Ravine, between two high and steep hills. They were subject to an immediate and near-constant barrage of enemy fire. By the end of the third day, the Germans had killed or wounded a quarter of the men, and those remaining Americans were reduced to hunkering down in their funk hole, hoping the next grenade didn’t land there and blow them to bits. They were hungry, thirsty, and running low on ammunition. The nearest water source was a muddy stream which the Germans guarded zealously. The Americans had no medical supplies with which to treat the groaning wounded. They were cut off from any supply routes. The weather was cold, wet, and gray.

The Major sent runners for help; none made it up the hillside without instantly being picked off by German snipers. Worse, due to an error in a message sent by carrier pigeon, Allied artillery misunderstood their location and began firing upon the trapped unit. More men were killed, but this time, by “friendly fire,” bullets inadvertently fired on them by their own American troops. Their situation was desperate. They needed to contact headquarters to get their own troops to stop firing upon them.

They had dispatched many carrier pigeons with messages for HQ but many were shot down by the Germans. It was mid-afternoon on October 4 when pigeon handler Private Omer Richards reached into the wicker pigeon basket to release yet another pigeon with a message.

They had dispatched many carrier pigeons with messages for HQ but many were shot down by the Germans. It was mid-afternoon on October 4 when pigeon handler Private Omer Richards reached into the wicker pigeon basket to release yet another pigeon with a message.

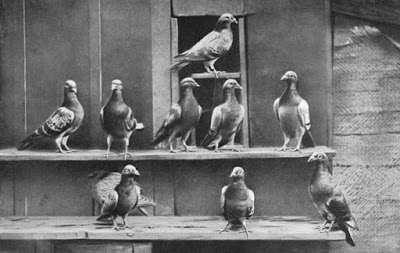

Photograph of the Western Front. Pigeons were used at the front to keep commanders in the rear up to date on the action and enemy movement. (National Archives Identifier 17391468)

There was one bird left and the embattled unit placed their hope on this two-year old bird. He was a seasoned carrier pigeon named *Cher Ami (which means “Dear Friend” in French). His home loft was Mobile #9 then stationed at the 77th Division message center about 25 miles away at Rampont. Cher Ami knew the way well. Private John Nell recalled,

“…Major Whittlesey turned our last homing pigeon loose with what seemed to be our last message….If that one lonely, scared pigeon failed to find its loft…we would go just like the others who were being mangled and blown to pieces….”

The message, written by Major Whittlesey on a page torn from the pigeon message book, was slipped into a tiny aluminum tube and clipped to the pigeon’s leg. Richards picked up Cher Ami and, around 3:00, lifted him skyward to fly. But the air was full of flying scrap steel and explosions, scaring the bird. He circled above the ravine before landing slightly farther down the hill in a burned-out, shrapnel-twisted tree.

Those men who had gathered around now began to yell at Cher Ami, “Go! Get out of here!” tossing sticks and rocks at him. But he refused to budge from his perch. Richards ended up shimmying up the tree after him. German shells exploded around Richards and bullets pinged off the bark near his hands. Cher Ami cocked his head at the soldier, preening his feathers out of utter fear. Finally Richards was able to reach up and shake the branch where the bird sat, roaring, “Fly!” Cher Ami took off, got his bearings, then headed back over the ravine in the direction of his dovecote.

The Germans took potshots at Cher Ami, trying to take him down, knowing full well his mission, but the bird continued to gain height and was soon lost to view. The American soldiers then scampered down the hill to move the wounded men to a place that was somewhat protected from the shelling. They piled up the dead bodies as a wall:

Bullets from across the brook thumped sickeningly into the corpse wall as the wounded hunkered down behind it.

It was 3:30 pm when the little bell of Mobil loft #9 rang, signaling that a messenger pigeon had just landed and passed through the gate into the coop. Corporal George Gault was on duty. What he found in the cage was a blood-stained gray and black checked cock pigeon squatting unsteadily and leaning to one side. He reached in and the pigeon collapsed entirely. Gently, he picked it up. Cher Ami was bleeding badly from a gaping wound in his chest and he was missing an eye. He was barely alive. Turning the hurt bird over to get the message, he found the little tube barely hanging on to what remained of the torn tendons of a missing leg. Gault read the message, gasped, then ran immediately to get the lieutenant on duty. They got General Milliken on the field telephone, reading the urgent message to him in words, not in code:

We are along the road parallel 276.4

Our own artillery is dropping a barrage directly on us.

For Heaven’s sake, stop it.

The division vet arrived to take the barely breathing bird away.

By 4:22, the American shelling had stopped. The Germans saw the opportunity and began a ferocious attack on the trapped 77th Division.

Finally, the Americans were able to push west through the Argonne to force the Germans to abandon the front facing the 77th Division. On October 8, reinforcements reached Whittlesey’s unit. Of the men trapped in that wooded ravine, 194 survived. Whittlesey’s unit came to be known as the Lost Battalion. The next month, on November 11, an armistice was signed between the warring factions that brought the war on the Western Front of World War I to an end.

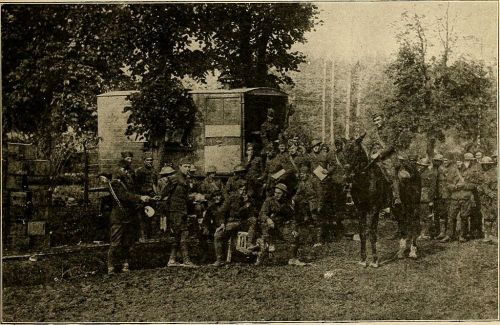

Members of the Lost Battalion getting their first meal at a regiment kitchen after the fight in the Charlevaux Ravine. Oct 1918. Public Domain

Cher Ami became the hero of the 77th Infantry Division. Army medics had saved his life. When he recovered enough to travel, the one-legged, one-eyed bird was put on a boat to the United States, with General John J. Pershing seeing him off.

For his heroic service, Cher Ami was awarded the French “Croix de Guerre” with palm. Eight months after his heroic flight, he died at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey on June 13, 1919, as a result of his wounds. Cher Ami was later inducted into the Racing Pigeon Hall of Fame in 1931, and received a gold medal from the Organized Bodies of American Pigeon Fanciers in recognition of his extraordinary service during World War I.

His stuffed body is on display at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History’s “Price of Freedom: Americans at War” exhibit in Washington, D.C. Cher Ami is one of the heroes of World War I. Although the Germans had shot him through the breast, blinded him in one eye, and shattered his leg, he continued to fly to reach help for the men of his division. He gave his life for his country and so that others could live.

For more on what scientists are learning about the homing instinct of pigeons, check out the new book, The Genius of Birds, by Jennifer Ackerman.

*Cher Ami, at the time, was a 2-year-old black and gray checkered English National Union Racing Pigeon Association cock #615, U. S. Army serial no. 43678 of the Signal Corps 1st Pigeon Division.

Sources:

- Smithsonian Natural Museum of American History: “Cher Ami”

- Laplander, Robert. Finding the Lost Battalion: Beyond the Rumor, Myths, and Legends of America’s Famous WW1 Epic.

- Doughboy Center: “The Big Show: The Meuse-Argonne Offensive.”

- wiki: “Cher Ami”

- American Battles Monument Commission: “Teaching and Mapping the Geography of the Meuse Argonne Offensive: Geography is War, A Case Study of the Argonne Forest and the Lost Battalion.”