Edith Head in a Paramount Pictures shot. Undated

It was summer vacation of 1924 and Edith Head, 27, wanted a new job. She was tired of making peanuts – $1500 a year – teaching French and art at the Hollywood School for Girls. She did have a husband but he was a heavy drinker. If Edith wanted to improve her quality of life, it was up to her to make it happen. However, there were few jobs open to women in the 1920s but secretarial work and teaching, and neither paid much.

One day, Edith spotted a classified ad in the Los Angeles Times. The Famous Players-Lasky Studio (later, Paramount Pictures) was looking for a sketch artist to create costumes for a new Cecil B. DeMille silent film, “The Golden Bed.” Edith wanted that job. One problem: Edith Head was no artist. She could not draw the human form.

She had exaggerated her qualifications to teach art when applying at the Hollywood School for Girls. True, she was highly educated, and was more than qualified to teach French – but not art. She had received a B.A. in Letters and Sciences with Honors in French at University of California at Berkeley (1919) and a Master’s Degree in Romance Languages at Stanford (1920) – pretty impressive for a girl who grew up in mining camps in the deserts of Mexico and Nevada. But she had no training in art. Once she had been hired at the girls’ school, she had swiftly enrolled in evening art classes at the Chouinard Art School to gain some artistic skill, learning just enough each night to keep one step ahead of the next day’s lesson for her students. So far, though, she could only draw seascapes.

Undaunted, Edith wrote the studio for an interview. She received a prompt reply, telling her to be at the studio the very next morning at 10 a.m., bringing sketches. Sketches? All she had to show of her own were seascapes.

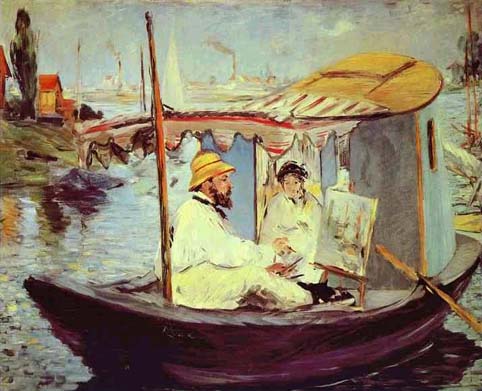

Agnes Ayres stars in Cecil B. DeMille’s 1921 film, “Forbidden Fruit” at Famous Players-Studio (later Paramount Pictures). In silent films, costume was an extremely important element. DeMille’s films were always lavish extravaganzas.

Edith did not know what to do but she knew that she wanted that job! Soon a light bulb went on in her brain:

That night I made the rounds at Chouinard (Art School) and collected all the students’ best landscapes, seascapes, oils, watercolors, sketches, life, art, everything.”

Some accounts say that Edith actually erased her friends’ names from their sketches and substituted her own. That next day, she appeared at the studio for her interview, a portfolio of other people’s work in hand. Howard Greer, head of the studio wardrobe department, described the interview in his memoirs:

…A young girl with a face like a pussy cat crossed with a Fujita drawing appeared with a carpetbag full of sketches. There were architectural drawings, plans for interior decoration, magazine illustrations, and fashion design. Struck dumb with admiration for anyone possessed of such diverse talent, I hired the gal on the spot.” (1)

Her salary was $40 a week, more than double what she made teaching.

The very next day, Edith reported for work. She sat at her drafting table, her canvas, blank. The jig was up. She couldn’t draw. Greer recalled:

[She] looked out from under her bangs with the expression of a frightened terrier.” (1)

Edith Head

Edith confessed that she had misrepresented her talent, taking credit for others’ work. Inexplicably, Greer did not fire Edith. Curiously, he took her under his wing and taught her how to sketch. Within six months, she sketched in his style and was quite accomplished. Later, when asked about misrepresenting her talent at the interview, she tossed off the fraud as “youthful and naïve indiscretion” and something she would never do again. (Two more lies!)

Whereas Edith dismissed the padding of her resume as an isolated incident, never to be repeated, designing colleague Natalie Visart did not see it that way. She commented:

Edith lied when the truth would have served her better.” (2)

Edith was to have few friends in life, among them, President Richard Nixon and wife Pat and actress Elizabeth Taylor. Biographer David Chierichetti said that

Her lies made her feel in control….Her lying – even more than her blazing ambition – was what turned people against her.”

Reportedly, director John Farrow would not let Edith work on his 1953 film, “Botany Bay,” as he had caught her in too many lies in the past.

But I digress.

Meanwhile, back to the summer of 1924, Edith was working at the bottom of the totem pole in the wardrobe design department.

My first big assignment was to do the Candy Ball costumes for Cecil B. de Mille’s film, “The Golden Bed.” I drew girls dressed as lollypops, peppermint sticks and chocolate drops….

Then came the crisis. I’d drawn very elongated girls with bodies like peppermint sticks and candy cane fingernails two feet long. Came the day of the shooting and, shortly after, came a blast from Mr. DeMille….The peppermint sticks had started cracking during the dance routine….whenever the dancers got within a half a foot of each other, the candy would stick.”

Also, under the hot lights on the set, the chocolate drops melted, and the production had to be halted. Edith went back to the drawing board and designed dresses studded with marshmallows for the peculiar film.

The “Candy Ball” scene from Cecil B. DeMille’s 1924 film, “The Golden Bed.” Men surround women wearing marshmallow dresses, pull off the sweets, and eat them.

In another of Edith’s costume faux pas, Director Raoul Walsh had to stop production on “The Wanderer” (1925) when one of the show’s elephants began eating its costume – wreaths of flowers and grapes and anklets of rose petals.

As Greer had suspected, Edith did have a natural talent for costume design and, before long, it showed up. She began to score more hits than misses. She became a savvy politician. Although the studio maintained that the actresses were not allowed any say in what they wore in the films, Edith got around that rule. She began to talk with the stars, asking each actress what she liked to wear, what she thought she looked good wearing. Edith became known as “The Dress Doctor,” as she approached the design of each actress’s costumes with their tastes and figures in mind, how they moved, talked, and were photographed.

Costume designer Edith Head and film star Gloria Swanson. Undated photo

In this way, she developed a large and loyal following of actresses such as Barbara Stanwyck, Elizabeth Taylor, and Grace Kelly even though there were stars like Mary Martin, Hedy Lamarr, and Claudette Colbert who didn’t like to work with her.

Edith boasted that she was a magician. She took ordinary women, and, through fashion magic, transformed them into screen sirens.

Accentuate the positive and camouflage the rest,” Edith liked to say.

Edith designed costumes for almost a thousand movies including westerns, biblical epics, war movies, and dramas. Her style was not flashy but flattered the star and advanced the story line. Here are some of Edith Head’s costume designs:

Mae West in “She Done Him Wrong,” 1933. Costumes by Edith Head.

Dorothy Lamour wearing a new version of a sarong in “Jungle Princess,” 1936. Costumes by Edith Head.

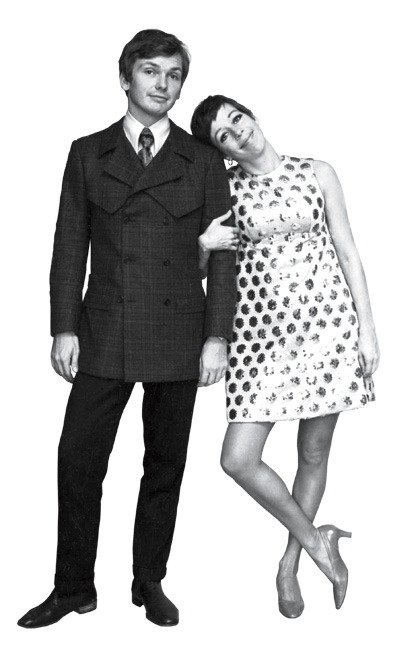

Barbara Stanwyck and Henry Fonda in “The Lady Eve,” 1941. Costumes by Edith Head.

Veronica Lake in “I Married a Witch,” 1942. Costumes by Edith Head.

Hedy Lamarr in “Samson and Delilah,” 1949. Costumes by Edith Head.

Gloria Swanson in “Sunset Boulevard,” 1950. Costumes by Edith Head.

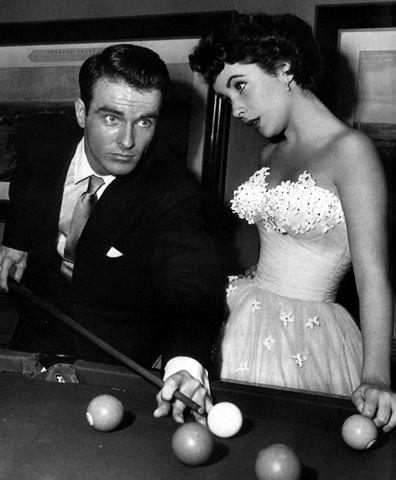

Elizabeth Taylor in “A Place in the Sun,” 1951. Costumes by Edith Head.

Audrey Hepburn in “Roman Holiday,” 1954. Costumes by Edith Head.

Edith Head sketch for Grace Kelly suit in “Rear Window,” 1954

Grace Kelly in “Rear Window,” 1954, wearing green suit shown in above sketch. Costumes by Edith Head.

Shown here with costar Jimmy Stewart, Grace Kelly wears the green suit shown in the sketch above, sans jacket. “Rear Window,” 1954. Costumes by Edith Head.

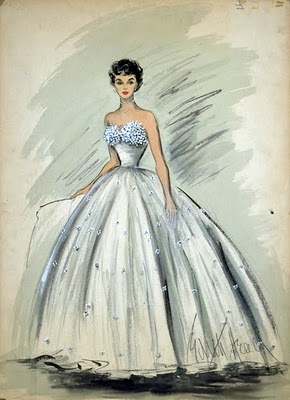

Sketch for evening gown by Edith Head for Grace Kelly in “Rear Window,” 1954.

From sketch above, Grace Kelly wears an evening gown from “Rear Window,” 1954. Costumes by Edith Head.

Grace Kelly models sunsuit from “To Catch a Thief,” 1955. Costume by Edith Head.

Grace Kelly in “To Catch a Thief,” 1955. Costumes by Edith Head.

Grace Kelly in “To Catch a Thief,” 1955. Costumes by Edith Head.

Edith Head sketch for gold masquerade gown for Grace Kelly in “To Catch a Thief,” 1955.

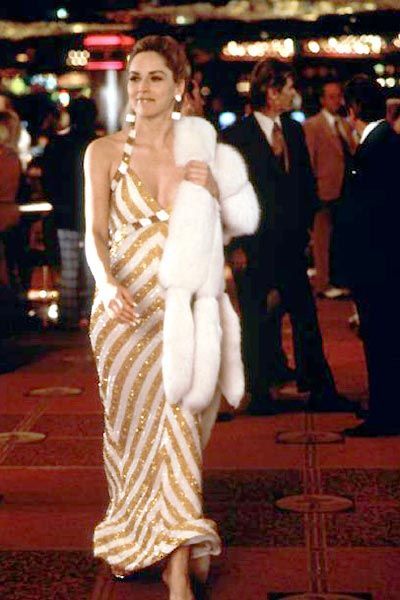

As in sketch above, Grace Kelly wears masquerade gown in “To Catch a Thief,” 1955. Costumes by Edith Head.

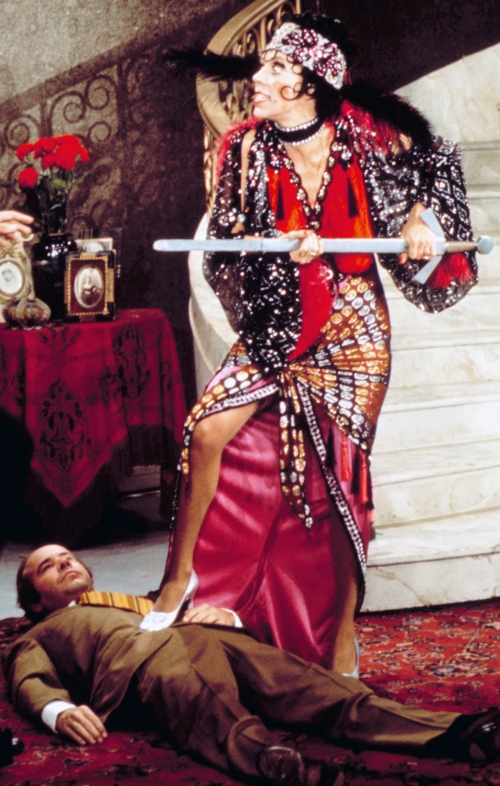

Anne Baxter in Cecil B. DeMille’s 1956 remake of “The Ten Commandments.” Costumes by Edith Head.

Edith Head was awarded eight Oscars and was nominated 35 times for best costume design.

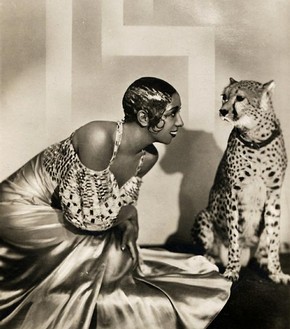

Legendary costume designer Edith Head (1897-1981) displays her 8 Oscar trophies. Originally, she wore blue tinted glasses because it allowed her to view fabrics as they would look in a black-and-white movie. Smoky lenses also made her inscrutable as well as disguising a slightly-crossed right eye. Undated photo

Her brilliant career, that began with a con, was marred by controversy. Often economical with the truth, she sometimes claimed credit for designs that were not her own. She accepted the Oscar for “Sabrina”(1955) although two gowns and one suit wore by Audrey Hepburn – the Parisian look that dominates the movie – were truly designed by then rising French designer Hubert de Givenchy.

Audrey Hepburn wears three dresses from the movie, “Sabrina,” 1954. Edith Head designed the “Cinderella” clothes that Audrey’s character wears before she travels to Paris. Upon her return, she wears a wardrobe designed by Hubert de Givenchy. Edith Head accepted the Academy Award for Best Costume Design and took credit for De Givenchy’s work.

Edith said the Oscar belonged to her because the costumes had been made in her department. In her acceptance speech, she did not thank de Givenchy. Worse still, when the little black dress became enormously popular, copied by the thousands by clothing manufacturers, Edith made sketches of it for books and appearances and signed them with her name. (3) Only after Edith’s death did Givenchy, a true gentleman, confirm that the black cocktail dress with the bateau neckline and ballerina skirt was his original design, and had been made under Edith’s supervision at Paramount.

In 1974, Edith Head was awarded her eighth and final Oscar for her work in “The Sting,” starring Robert Redford and Paul Newman. In her trademark bangs, bun, and tinted owl glasses, Edith flitted happily onto the stage, trilling:

“Just imagine dressing the two handsomest men in the world, and then getting this!” she said, holding out her award.

Robert Redford and Paul Newman play ping pong. Undated photo.

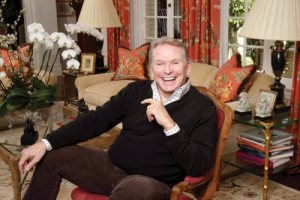

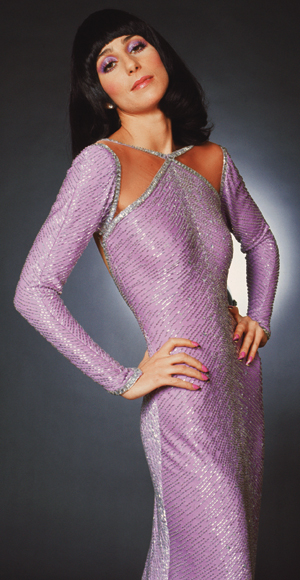

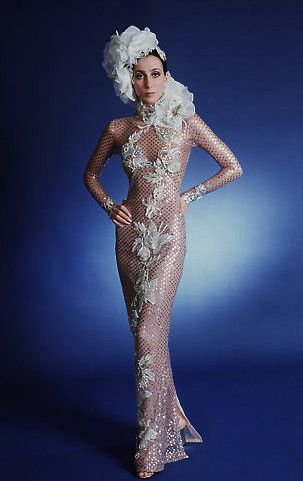

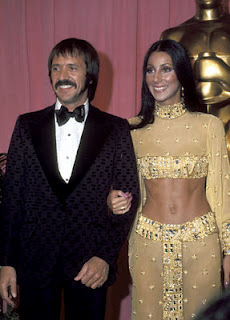

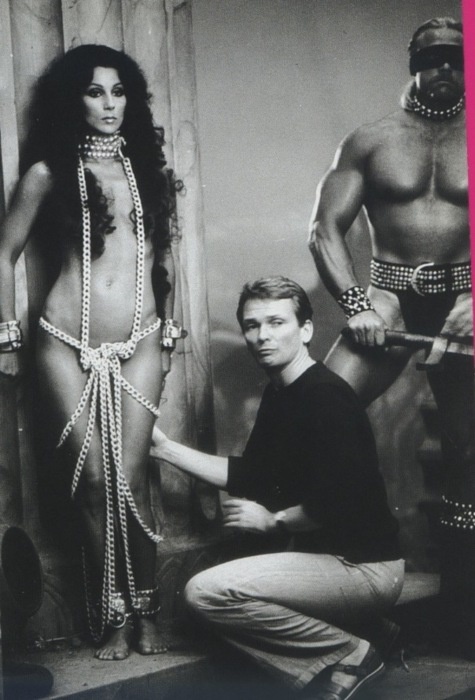

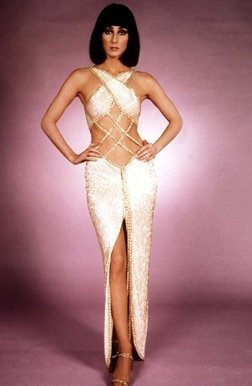

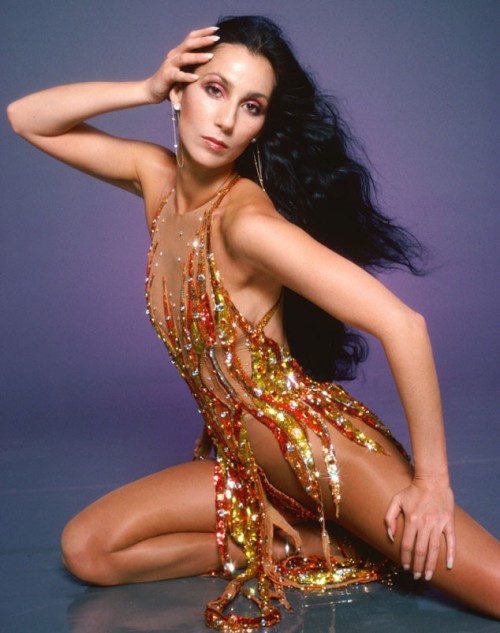

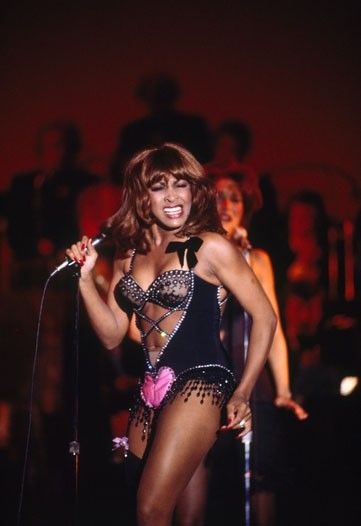

She was promptly sued by a costume illustrator who said the work on “The Sting” was hers, not Edith’s. Famous designer Bob Mackie, Cher‘s favorite, who had also worked in the Paramount costume department, said of Edith:

She got more press out of The Sting than anything she ever did and she didn’t even do it.” (4)

(1) Greer, Howard. Designing Male: A Nebraska Farm Boy’s Adventures in Hollywood and with the International Set. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1951.

(2) Chierichetti, David. Edith Head: The Life and Times of Hollywood’s Celebrated Costume Designer. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2003.

(3) Head, Edith. The Dress Doctor. Boston: Little, Brown, 1959.

(4) Jorgensen, Jay. Edith Head: The Fifty Year Career of Hollywood’s Greatest Costume Designer. New York: Lifetime Media, 2010.

Readers, for more on Edith Head and her costume design, click here.

Read Full Post »