President Lincoln and son "Tad" (Thomas) in a February 9, 1864 photograph by Anthony Berger of the Brady Studio.

April 11, 1865 became the official day of celebrating the end of the Civil War. An even larger crowd was assembled on the White House lawn than the night before. (See last post.) The band was playing triumphant music, people were waving banners and shouting, “Hoorah!” and calling out for President Lincoln to speak. It was evening, but Washington D.C., was blazing with light. The Capitol, other government buildings, the White House, and private homes were lit up from within to ring in the good news.

A great cheer went up from the crowd when the President appeared on the second-floor balcony to deliver his speech. There he stood patiently and quietly as waves of applause rolled toward him. Finally, the crowd settled down and Lincoln, holding a candle in his left hand and his notes in his right, prepared to speak. But the juggling of the candle and his manuscript instantly proved awkward for the president. So he gave the candle to his friend Noah Brooks to hold. Son Tad knelt at his feet to catch each fluttering page of his father’s notes as he dropped them.

The crowd was silent when Lincoln began:

“Reuniting our country is fraught with great difficulty…and we differ among ourselves as to the mode and manner and means of reconstruction….”

Lincoln continued in this same vein, spelling out in greater and more boring detail the plans he had for reuniting the torn nation. The crowd was somewhat taken aback by the president’s tone. This was not the speech they’d expected. They had come to hear a rousing speech, praising the Union troops for their bravery and sacrifice, but, instead their president was droning on with no merriment, skipping past the present and jumping into the future without pausing to savor victory. Not waiting for the end of the president’s speech, some members of the crowd drifted away no doubt to find a jazzier way to spend the celebration.

John Wilkes Booth (1838-1865)

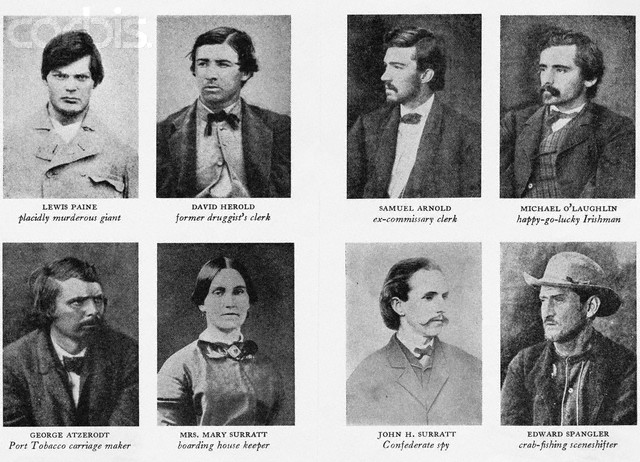

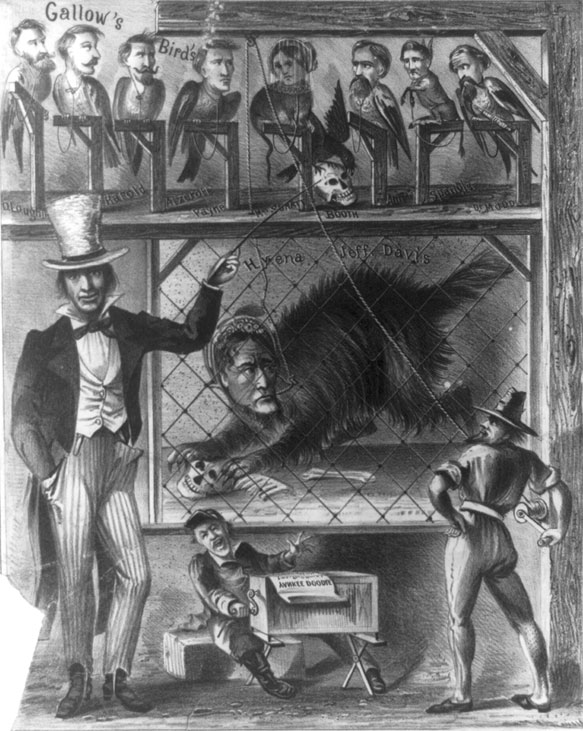

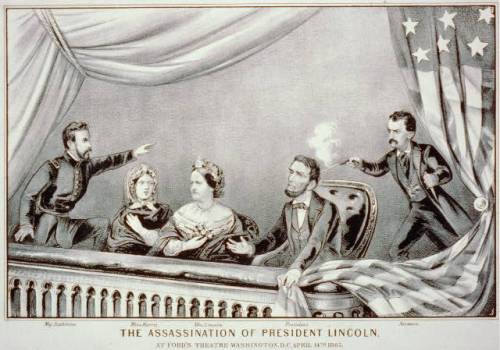

One of the people in the crowd that day was the famous young actor and Southern sympathizer John Wilkes Booth. Along with him were drugstore clerk David Herold and former Confederate soldier Lewis Powell, also known as Lewis Payne. Just weeks earlier, these three men and five others had been planning to kidnap Lincoln and exchange him for Confederate P.O.W.s. But now that the Confederacy had collapsed, Lee had surrendered, and Rebel P.O.W.s were being released, there was no incentive to kidnap the president. Still, Booth wanted to act. He hated Lincoln and considered him a tyrant along the lines of Julius Caesar. He was determined to do something heroic in defense of the South and to punish Lincoln.

Booth was startled to hear what the President said next. Lincoln said something that no other president had ever said publicly. He told the crowd that he was in favor of granting some black men the right to vote, especially, “the very intelligent and those who served our cause as soldiers.” One hundred eighty thousand black men had served in the Union Army.

Booth went ballistic. He turned to his fellow co-conspirator Powell. “That means nigger citizenship. That is the last speech he will ever make,” he vowed. He begged Powell to shoot Lincoln then and there. When Powell said no, Booth proclaimed, “By God, I’ll put him through.”

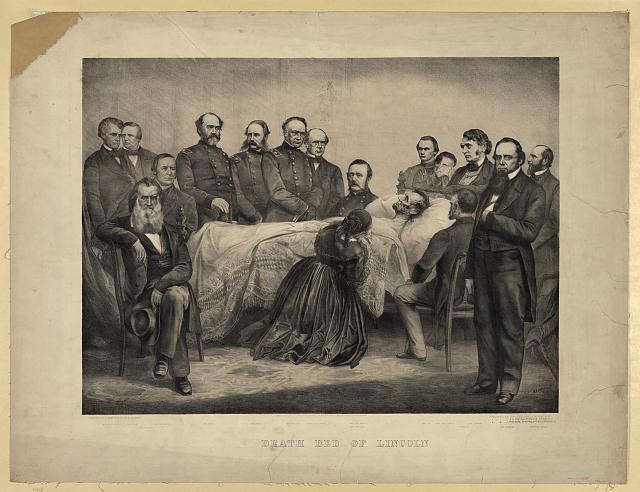

Booth was true to his word. It was the last speech Lincoln ever made. Four days later, the president would be dead, killed by a bullet fired into his head by John Wilkes Booth.

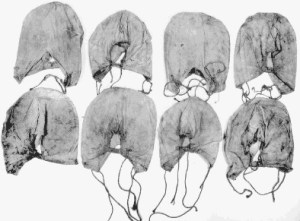

For related posts on this blog, see left sidebar “Categories.” Select Mary and Abraham Lincoln. In particular, you might enjoy reading “The Lincoln Assassination: Mary Surratt & the 7 Hoods.”

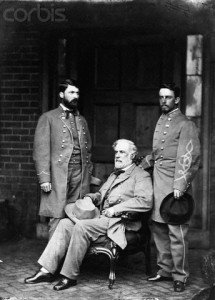

April 14, 1865, was one of the happiest days of Abraham Lincoln’s life. It was Good Friday. General Robert E. Lee had surrendered five days earlier and the Civil War was over. The Union had been saved. Lincoln had a relaxing breakfast with his 21-year-old son Robert, whom he called “Bob,” who had just arrived for a visit.

April 14, 1865, was one of the happiest days of Abraham Lincoln’s life. It was Good Friday. General Robert E. Lee had surrendered five days earlier and the Civil War was over. The Union had been saved. Lincoln had a relaxing breakfast with his 21-year-old son Robert, whom he called “Bob,” who had just arrived for a visit.