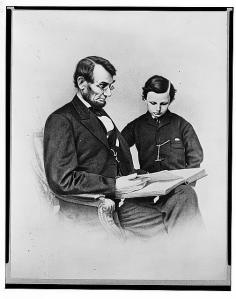

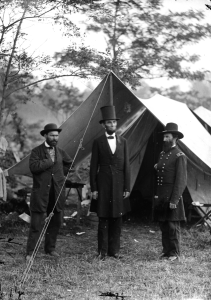

Abraham Lincoln, February 5, 1865. He would live less than 3 more months.

It was the morning of Friday, April 14, 1865, the last full day of Abraham Lincoln’s life. It was a beautiful spring day. The president was looking forward to an evening at the theater. Plays relaxed him, expecially comedy. There were some who looked down on him for being a theater-goer. They considered it lowbrow entertainment, especially for the commander-in-chief. Who were they to deny Lincoln a few minutes away from his troubling thoughts?

But that was all behind him now. The War Between the States was over. The terrible suffering had come to an end. Abe and his wife, Mary, had lost two sons to illness. That afternoon, he and Mary took a leisurely carriage ride. They spoke of the future together. Abraham was very happy. He said to Mary:

“We must both be more cheerful in the future.”

Abraham Lincoln’s favorite carriage. It was the carriage that took him, Mary, Major Henry Rathbone, and Clara Harris to Ford’s Theatre on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. The carriage is a 4-passenger barouche. When the doors are opened, steps unfold.

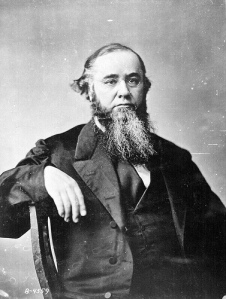

Major Henry Rathbone

Shortly after their return to the White House, they dressed for the theater – Ford’s Theater – to see “Our American Cousin” starring Laura Keene. Mary and Abe had had a dickens of a time finding someone to attend the performance with them. They had invited 12 people and all had declined. It was Good Friday, the most solemn day on the Christian calendar, and not a day many folks sought entertainment. Most were busy, some disapproved of theater in general. The Grants – especially Julia, the General’s wife – could not stand the idea of being confined in a theater box with Mary and her explosive temper.

Clara Harris photographed by Mathew Brady, ca. 1860-68.

Finally, a young couple the Lincolns were fond of – Major Henry Rathbone and Clara Harris – accepted their invitation. Henry and Clara had just become engaged. Oddly enough, Clara was Henry’s stepsister. When Henry’s father died, his mother married Ira Harris, Clara’s father.

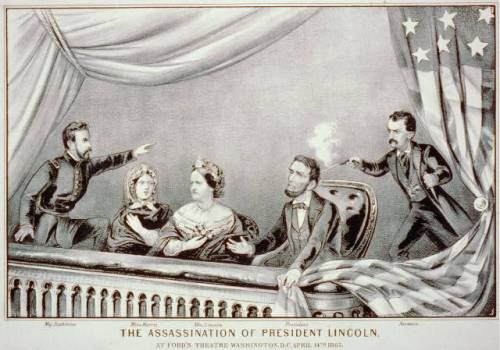

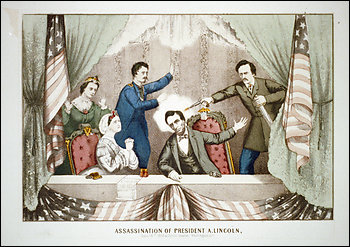

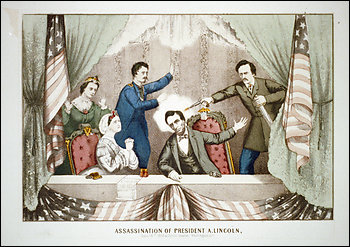

The two couples arrived at Ford’s Theater in the president’s carriage after the performance had already begun. As the four entered the presidential box, decorated with American flags and a painting of George Washington, the actors froze on stage. The orchestra struck up “Hail to the Chief.” The audience clapped, cheered, and waved.

“The president,” remembered one theater-goer, “stepped to the box-rail and acknowledged the applause with dignified bows and never-to-be-forgotten smiles.” (1)

The applause died down as the Lincolns, Clara and Henry took their seats. Abraham settled into a rocking chair Ford had brought up from his office especially for him. He sat on the far right of the box. To the left, Mary pulled her chair close to her husband’s, nestling up to him at one point, and slipping her arm through his. On the left side of the box, Clara sat in a stuffed chair. Henry sat on a small sofa behind her and in the back of the box. Mary fretted that Henry couldn’t see the stage well from the sofa and said so.

One of the biggest laughs in the play came in the third act when the male lead delivered this line:

“Don’t know the manners of good society, eh?” he paused. “Well, I guess I know enough to turn you inside out, old gal – you sockdologizing old mantrap.”

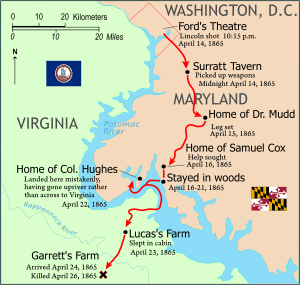

This line always got a big laugh. Tonight was no exception. The audience – including the president – laughed and clapped. They made so much noise that only the people in the box heard the crack of a gunshot, as actor John Wilkes Booth had planned. Booth had crept into the presidential box and, with a derringer, shot the president in the back of the head.

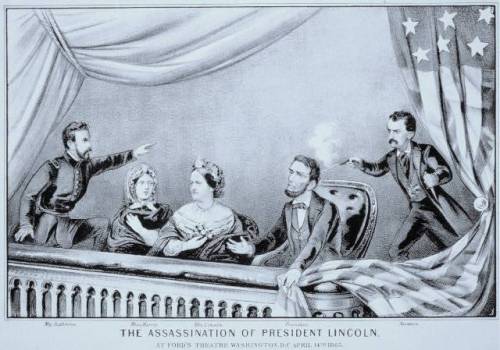

The “Assassination of President A Lincoln” showing, from left to right, Clara Harris, Mary Todd Lincoln, Major Henry Rathbone, President Abraham Lincoln, and John Wilkes Booth

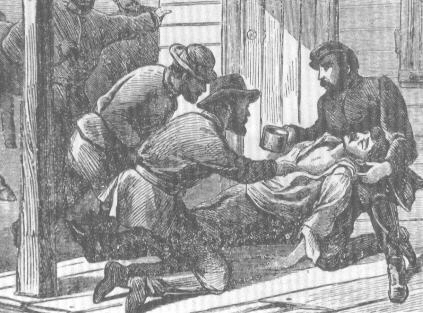

The rest was blue gunsmoke and confusion. The president was slumped forward in his chair with no visible wound. He looked as if he was sleeping. Henry grabbed the gunman who held his gun in one hand and a dagger in the other. Booth dropped the gun and slashed Henry in the arm and the head. Because of Henry’s interference, Booth was unable to make a clean jump out of the presidential box onto the stage below. Booth caught his foot as he jumped, landing on the stage at a weird angle, and breaking his leg. Henry shouted into the audience, “Stop that man!” Clara yelled, “The president has been shot!”

John Wilkes Booth flees across the stage of Ford’s Theater after having assassinated President Lincoln. He shouts, “Sic semper tyrannis!” (Latin for “Thus it shall ever be for tyrants,” the Virginia state motto) and, perhaps also, “The South is avenged.”

Though Henry was weak from loss of blood and his wounds were serious, the president’s wound was mortal. By the next morning, the president was dead.

Henry survived the attack and, in 1867, he and Clara were married. They had three children. But all was not well with Henry. Perhaps because of his head wound, his mental health rapidly deteriorated. He heard voices and believed he was being persecuted and tortured. He became jealous of his wife’s attention to their children. Clara lived in utter terror of what Henry might do.

Eighteen years after Lincoln’s assassination, Henry Rathbone reenacted Booth’s brutal attack on President Lincoln – within his own home. Armed with knife and pistol, Henry attacked his family, murdering Clara with a pistol, trying to kill his children, then stabbing himself. He lived and was declared insane. He was institutionalized in Germany for the rest of his life.

(1) Fleming, Candace. The Lincolns: A Scrapbook Look at Abraham and Mary. New York: Random House, Inc., 2008.

Read Full Post »

![1115 john tenniel_thumb[2] "The Mad Hatter's Tea Party." ="Though he did not create the expression "mad as a hatter," author Lewis Carroll did create the eccentric character in his book, Alice in Wonderland (illustrations by Sir John Tenniel), first released in London in 1865, coincidentally, the year Lincoln was assassination. The hatter in the book is an eccentric fellow with wacky ideas and incoherent speech, attributes attributed to hatters of the day. Mercury was used in hatmaking and its poisonous vapors caused neurological damage on the hatters.](https://lisawallerrogers.files.wordpress.com/2009/06/1115-john-tenniel_thumb2.jpg?w=500)