Boston Corbett (1832-?) photographed in 1865

The man who killed John Wilkes Booth was as mad as a hatter. His name was Boston Corbett. Actually, his name was not originally Boston Corbett, but Thomas T. Corbett. He became a reborn evangelical Christian while in Boston which he took as his new name. He began to wear his hair long like Jesus. He became a religious fanatic. Those who knew him said he was “different.” Boston Corbett was as mad as a hatter.

Boston Corbett was as mad as a hatter because he was a hatter – at a time when mercury was used in the felt hatmaking process. Hatmakers breathed the mercury vapors which caused mercury poisoning. Mercury damages the nervous system, producing symptoms such as drooling, twitching, paranoia, hallucinations, and agitation. It was probably mercury poisoning that caused the mental problems that dogged Corbett all his days.

![1115 john tenniel_thumb[2] "The Mad Hatter's Tea Party." ="Though he did not create the expression "mad as a hatter," author Lewis Carroll did create the eccentric character in his book, Alice in Wonderland (illustrations by Sir John Tenniel), first released in London in 1865, coincidentally, the year Lincoln was assassination. The hatter in the book is an eccentric fellow with wacky ideas and incoherent speech, attributes attributed to hatters of the day. Mercury was used in hatmaking and its poisonous vapors caused neurological damage on the hatters.](https://lisawallerrogers.files.wordpress.com/2009/06/1115-john-tenniel_thumb2.jpg?w=500)

"The Mad Hatter's Tea Party." Though he did not create the expression "mad as a hatter," author Lewis Carroll did create the eccentric character of the hatter in his book, Alice in Wonderland (illustrations by Sir John Tenniel), first released in London in 1865, coincidentally, the year Lincoln was assassinated. The hatter in the book is an eccentric fellow with wacky ideas and incoherent speech, characteristics attributed to many hatters of the day, suffering from mercury poisoning. Mercury was used in hatmaking and its poisonous vapors caused debilitating neurological damage to the hatters, resulting in a complete mental breakdown.

As I was saying, Corbett’s job – daily breathing in the noxious mercury fumes while he made felt hats – was making him go insane. By July 16, 1858, Corbett had become so insane that he picked up a pair of scissors, took off his pants, and castrated himself. After doing the strange deed, he nonchalantly dressed again and went out to a prayer meeting, where he ate heartily and then took a walk. Corbett did, however, end up seeing a doctor to receive treatment for his self-mutilation. (1)

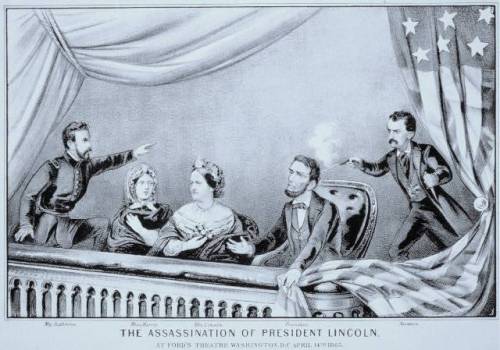

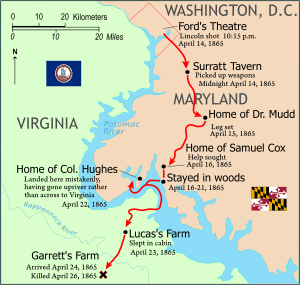

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Corbett enlisted in the Union army. He reenlisted three times and was made sergeant. In the days following President Lincoln’s assassination, he was selected as one of the 26 soldiers in the 16th New York Cavalry commissioned to pursue and capture the fugitive assassin John Wilkes Booth. On April 26, 1865, Corbett and the others cornered Booth and his coconspirator David Herold in a tobacco barn on Richard Garrett’s Virginia farm. Herold gave himself up.

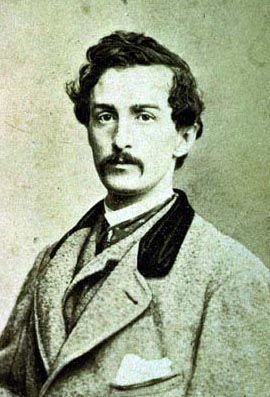

Lincoln assassin John Wilkes Booth

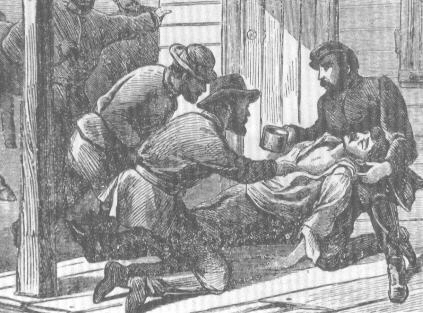

Booth refused to surrender, so the soldiers set the barn on fire, hoping to smoke him out. Corbett watched Booth through a large crack in the barn wall. As Booth moved about inside the burning barn, Corbett stuck his Colt revolver through the crack and aimed at the unsuspecting Booth, a full 12 feet away. Corbett’s bullet struck Lincoln’s killer in the neck, puncturing his spinal cord. Booth did not die at once.

When Corbett was questioned about his unilateral decision to kill rather than to capture Booth alive, he replied:

“God Almighty directed me.”

Back in Washington, Corbett was placed under technical arrest, but Secretary of War Edwin Stanton refused to prosecute the man many considered a hero. Stanton said, “The rebel is dead. The patriot lives.” Corbett collected $1653.85 in reward money.

Famous now, Corbett returned to the hat trade, first in Boston then in Connecticut and New Jersey. Further exposure to mercury caused his already volatile and erratic behavior to escalate. He got into frequent arguments which involved flashing his revolver in men’s faces.

He grew paranoid.

Then, in 1878, he made a radical life change. He moved to Kansas to live in a dugout; his home was nothing more than a hole in a hill with a stone front and a patchwork roof. He lived simply, sleeping on a homemade bed. He bought a flock of sheep. He began to give religious lectures that invariably turned into incoherent rants. He kept a number of firearms.

Improbably, in 1887, Corbett was appointed assistant doorkeeper to the Kansas House of Representatives in Topeka. Shortly after his appointment, he got crosswise with some men, pulled out a gun, threatened them, and got arrested. He was declared insane and sent to the Topeka Asylum for the Insane.

But he didn’t stay there. A little over a year later, he stole a horse that had been left at the asylum entrance and escaped. Little is known about where he went after that. Some say Mexico. He may have become a traveling salesman for a medicine company in Oklahoma Territory and Texas. No one knows what became of the man who killed John Wilkes Booth. That may forever remain a mystery.

(1) The actual hospital record can be read on page 59 of Lincoln and Kennedy: Medical & Ballistic Comparisons of their Assassinations by Dr. John K. Lattimer.