Abolitionists, powerless to stop the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, nonetheless, held numerous protest conventions. The law, which would be passed by Congress in September, gave unbridled power to arrest fugitive slaves in the North and return them to slavery in the South.

The most memorable and audacious of these protest conventions was the Fugitive Slave Law Convention, held in Cazenovia, New York, on August 21-22, 1850, and organized by New York abolitionist firebrand Gerrit Smith. On the first day, nearly fifty fugitive slaves and 400 others met inside the Free Congregational Church of Cazenovia. Hundreds of others gathered outside the building as there was no more space in the pews. Because of the overflowing crowd, the meeting was moved outdoors into Grace Wilson’s apple orchard.

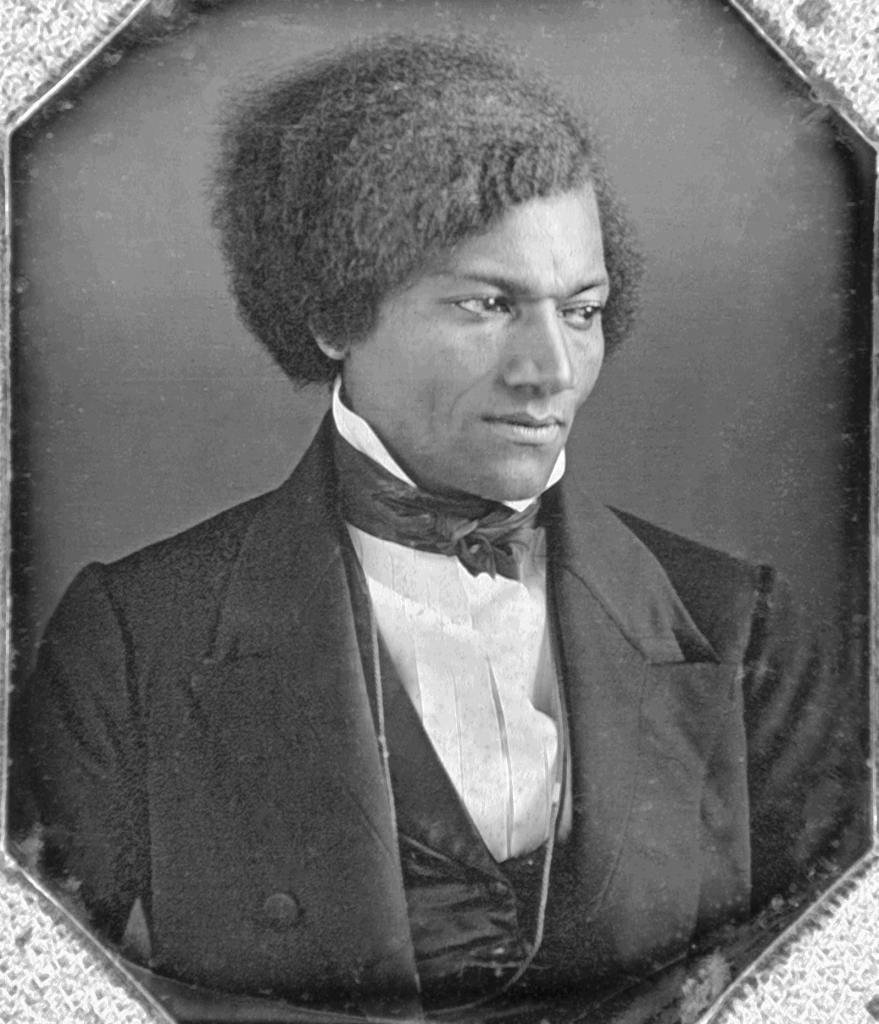

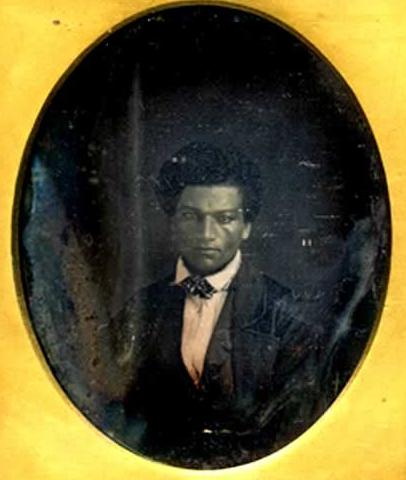

The resolutions and position statements passed were radical in nature. Chairing the meeting was former slave Frederick Douglass, editor of the North Star newspaper. Using his trademark powerful oratory, Douglass declared all slaves to be prisoners of war. He called slaveholders “robbers” and warned the nation that an insurrection was inevitable should slaves not be liberated. Slaves still held in bondage were encouraged to run away, steal horses and money, and use violence if necessary. Mary Edmonson, 18, a freed slave, spoke often at abolitionist gatherings, and, at Cazenovia, made an eloquent speech in support of Douglass’ resolutions and proposed measures. Other abolitionist celebrities present included Emily Edmonson who, along with her sister, Mary, had been among the fugitive slaves on the Pearl, Gerrit Smith, and the Rev. Samuel J. May.

In 1994, a daguerrotype of this storied meeting was found in the Madison County Historical Society.

William L. Chaplin, an associate of Gerrit Smith’s who had arranged the ill-fated April 1848 escape of 77 Washington, D. C. slaves aboard the Pearl, had been scheduled to make a dramatic appearance with some fugitive slaves he had rescued from the South, but things did not turn out well for Chaplin. It had been foolhardy for him to attempt to rescue slaves belonging to two Georgia congressmen! His attempt was foiled, a posse was organized, Chaplin and the fugitives were pursued, found, Chaplin was hit with a club, one fugitive was quickly captured, and the other surrendered shortly. Chaplin was held in the Washington City Jail. His supporters raised the $6,000 bail but Chaplin was not freed. He was then handed over to the Maryland authorities who put him in the Rockville, Maryland jail, where he faced additional and more serious charges. Bail was set at a whopping $19,000.

Emily and Mary Edmonson spent much of September 1850 making appearances in small towns across New York to raise money for Chaplin’s bail. The teenagers had lovely singing voices. They sang and begged for funds on Chaplin’s behalf, even on Sundays, the Sabbath, but, as they believed that Chaplin was doing the Lord’s work, they did not consider their actions sinful. They did this in gratitude. It had been Chaplin who had secured the money for their freedom following their sale south.

Finally, in January 1851, the entire $19,000 was raised and Chaplin was released. He then fled, refused to appear for trial, forfeiting $25,000. Chaplin made little effort to reimburse those who had donated money to his release. Some people were left penniless after their donations. Chaplin abandoned his abolition activity. He married Theodosia Gilbert and together they operated the Glen Haven Water Cure Spa in New York.

Sources:

Brockell, Gillian. “Desperate for Freedom, 77 enslaved people tried to escape aboard the Pearl. They almost made it.” The Washington Post. April 16, 2021.

Conkling, Winifred. Passenger on the Pearl: The True Story of Emily Edmonson’s Flight From Slavery

wikipedia: Edmonson sisters