In this 1934 Diego Rivera mural, "Man, Controller of the Universe," Leon Trotsky makes an appearance.

In 1937, Frida Kahlo took a new lover. He was Leon Trotsky, the Russian revolutionary. When Frida met Trotsky, he was a man without a country. He had come to Mexico as a political refugee. He had been expelled from the Soviet Union by his archrival Josef Stalin. For nine years, Trotsky and his wife Natalia had lived in exile, searching in vain for political asylum in Turkey, France, and Norway, with no country wanting to admit them permanently, fearing reprisals from the Soviets (they threatened, for instance, to cancel their large exports of Norwegian herring).

Trotskyites all over the world were frantic with worry. Frida’s husband Diego Rivera, a well-known Communist and recent convert to Trotsky’s brand of Communism, came to the Trotskys’ rescue, intervening on their behalf with the Mexican government to grant them asylum in Mexico City.

Diego was hospitalized with eye and kidney problems when, on the morning of January 9, 1937, the steamship carrying Trotsky and his wife arrived in Tampico harbor. Natalia Trotsky refused to disembark until she was sure she was safe and saw some familiar faces. She had lived for years surrounded by guards and under threat by assassination by Stalin’s agents. She was afraid to leave the boat. Finally a government cutter approached carrying a welcoming party of Mexican authorities, Communist party members, journalists, and Frida Kahlo, who was standing in for the ill Diego. (1)

Satisfied they were in safe hands, Trotsky and Natalia walked down the wooden pier to freedom. He, wearing tweed knickerbockers and a cap, and carrying a briefcase and a cane, walked with his chin held high, his stride that of a proud soldier. She, a little dowdy in a suit and looking worn and worried, watched her feet so as not to trip on the rought planks of the narrow dock. Just behind them walked Frida, lithe and exotic in her rebozo (shawl) and long skirt.” (1)

Natalia and Leon Trotsky arriving in Tampico, Mexico, January 9, 1937, greeted by artist Frida Kahlo, center.

A train carried them to the capital where Rivera awaited them. The two great men, lovers of Communism, embraced, then all four drove quickly to Frida’s childhood home in Coyoacan called the Blue House. There the Trotskys would live rent-free, off and on for two years, with their every need and want attended to by Frida, Diego, Cristina Kahlo, friends, and Trotskyite party members who acted as guards, chauffeurs, escorts, and advisers.

Diego had the blue house turned into a fortress. The windows that faced the street were filled in with adobe bricks. Police stood guard during the day, Trotskyites by night. Diego even bought the property next door and connected the two buildings to provide a larger garden and a wing with a studio for Frida, as she would be the Trotskys’ chief hostess.

"Fulang-Chang and I," by Frida Kahlo, 1937. At age 29, Frida was at her loveliest.

It didn’t take long for both Frida and Trotsky to start making eyes at each other. Both were notorious for conducting extramarital love affairs. Trotsky and Frida spoke English to one another, which left Natalia guessing what they were saying, as she didn’t speak English (and Diego’s English was deplorable).

The two couples saw a lot of each other. Frida was openly flirtatious with Trotsky, calling him “love” and hoping to make Diego insanely jealous in retaliation for his affair with her sister Cristina (See previous post, “Frida Kahlo: I Can’t Live, if Living is Without You!”).

Trotsky slipped love letters into books he loaned Frida. By late spring of 1937, the two were immersed in a full-fledged love affair. They met secretly at Cristina Kahlo’s house, which Diego probably had bought her. Frida nicknamed Trotsky “Piochitas” (little goatee) for his white beard and called him also “el viejo,” as he was 58 years old while she was only 29.

By late July, though, the affair had fizzled out. Frida had proved to herself that she could still attract men and returned, as usual, to doting on Diego. The end may have come about, though, because Natalia and Diego discovered the affair (which could have been Frida’s intention all along). Over time, Diego and Trotsky had several philosophical disagreements about Communism. Diego ceased to be a Trotskyite. Soon, the couples grew apart, although the Trotskys remained in Mexico, they moved out of the Blue House.

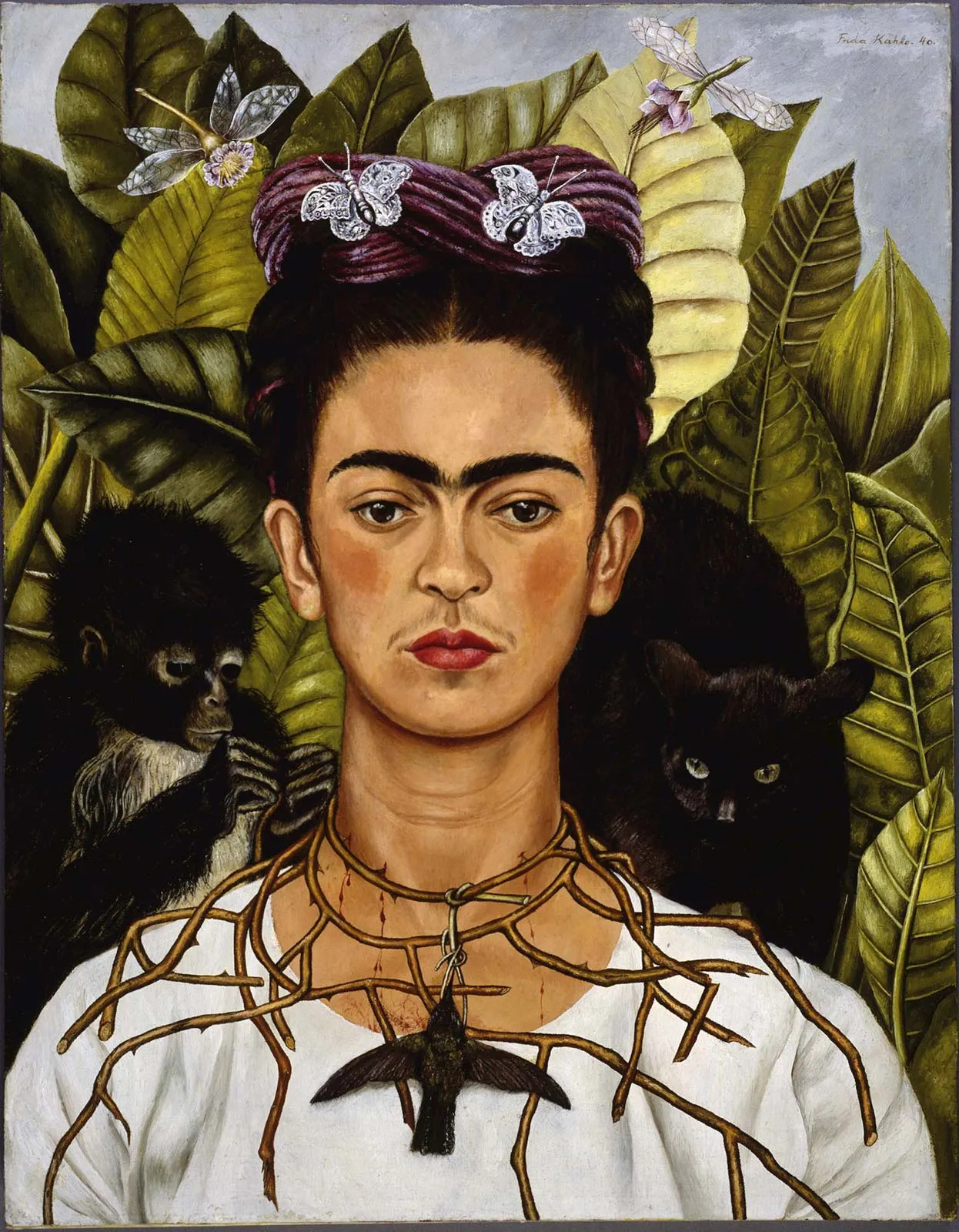

Frida, though, remained friends with Trotsky. She painted a self-portrait for him. The painting shows her standing between two curtains, holding a piece of paper that says in Spanish,

‘To Trotsky with great affection, I dedicate this painting November 7, 1937. Frida Kahlo, in San Angel, Mexico.’ The date was significant because it was both Trotsky’s birthday and the anniversary of the October Revolution, according to the Gregorian calendar.” (2)

"Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky Between the Curtains," by Frida Kahlo, 1937

Less than three years later, Trotsky was dead. On August 20, 1940, he was attacked in his home by an assassin sent by Stalin named Ramón Mercader, who buried the pick of an ice axe into Trotsky’s skull. Trotsky died the next day.

Leon Trotsky on his Deathbed, August 21, 1940

Frida was distraught. She called Diego in San Francisco to tell him the news.

“They killed old Trotsky this morning,” she cried. “Estupido! It’s your fault that they killed him. Why did you bring him?” (1)

Frida had met the assassin once in Paris and had invited him to her house in Coyoacan to dine, which placed her under suspicion. She was picked up by the Mexican police and interrogated for 12 hours, before being released, two days later, without charge.

(1) Herrera, Hayden. Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, Inc., 1983.

(2)Zamora, Martha. Frida Kahlo: The Brush of Anguish. San Francisco, Chronicle Books, 1990.