The Mysterious Affair at Styles by Agatha Christie (1920) introduces retired Belgian detective Hercule Poirot. This is Christie’s first published book.

It was all a bit of a lark! There they were, Archie and Agatha Christie, just trolling along, living their ordinary lives in their Battersea Park flat, with him working in London, her writing mystery novels at home, the two of them raising little Rosalind, poor as church mice, unable to afford any amusements, when, in late 1921, Archie’s old schoolmaster Major Belcher popped into their lives and changed everything.

Belcher had a new job. At dinner, he described it:

“‘You know this Empire Exhibition we’re having in eighteen months’ time? Well, the thing has got to be properly organized. The Dominions have got to be alerted,…to cooperate in the whole thing. I’m going on a mission – the British Empire Mission – going round the world, starting in January.

What I want is someone to come with me as financial adviser. What about you, Archie?…You’re just the man I want.'” (1)

The trade mission would last ten months, with first class accommodations in South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada. Even better, Belcher continued, Agatha could accompany Archie and, to top it off, he suggested that, on a stopover between duties in New Zealand and Canada, they pause in Hawaii for a month’s holiday.

The trade mission would last ten months, with first class accommodations in South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada. Even better, Belcher continued, Agatha could accompany Archie and, to top it off, he suggested that, on a stopover between duties in New Zealand and Canada, they pause in Hawaii for a month’s holiday.

At that point in their lives, on their tiny incomes, Archie and Agatha could only expect a two-week holiday once a year. And now this offer! Round the world and Hawaii, too? All expenses paid and first class accommodations as representatives of Great Britain! (The British Empire was at the height of its territorial extent.) Who could say no to that?

Of course there were risks to consider, they reminded themselves. Money would be tight and Archie might not be able to get his old job back upon his return. They would be leaving two-year-old Rosalind with Agatha’s sister, mother, and nurse for almost a year and be essentially incommunicado except for the occasional telegram and letters carried by ships.

After considerable thought, though, they accepted Belcher’s generous offer. Archie quit his London job. A lot of luck had come their way and they would be fools to pass it up, they decided. They were young and adventurous; Archie was Colonel Christie, having served in the Royal Air Force in the First World War. Agatha was 31; Archie, 32. They have never been ones to play it safe, having eloped despite Archie’s mother’s objection to his marrying Agatha. They were due for a bit of fun.

They packed their steamer trunks (Agatha packed her swimsuit), closed up the flat, and kissed Rosalind goodbye. On January 20, 1922, the mission party left Southampton on the RMS Kildonan Castle.

RMS Kildonan Castle

The weather was atrocious and Agatha was confined to her cabin with seasickness until they reached the Portuguese isle of Madeira, west of Morocco. She was finally able to enjoy the rest of the (smoother) voyage south to the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa, snapping photo after photo of her travel companions.

Agatha Christie and Archie Christie on board the RMS Kildonan Castle. Jan.-Feb. 1922. Photo from the Christie Archive

Seventeen days later, the Kildonan Castle docked at Cape Town, South Africa. The V.I.P.s were greeted by the Deputy Trade Commissioner and shown to their rooms at the Mount Nelson Hotel.

The 1922 British Empire Exhibition Trade Mission with from l. to r. Colonel Archie Christie, Major Belcher, Secretary Bates, and Agatha Christie. Photo from the Christie Archive

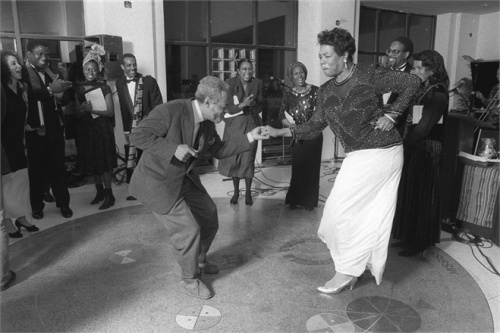

For the next two months, both Archie and Agatha were swept up in a whirl of meetings, lunches, teas, field trips, dinners, dances, bridge and golf games with government officials and local notables. It was always go-go-go! Agatha visited a diamond mine in Kimberley, got misty at Victoria Falls, saw crocodiles and hippos swimming at Livingstone. But the thing she enjoyed most of all in South Africa was the sea bathing.

The Cape Peninsula, South Africa, where Cape Town is located. This is False Bay.

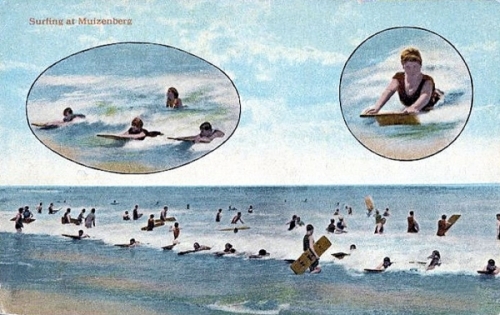

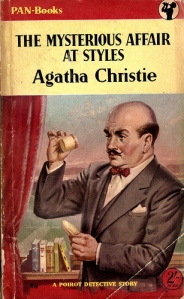

Whenever she and Archie and others could steal away, they took the train from Cape Town to Muizenberg on False Bay and went “surf bathing” – lying flat on a light, thin board and riding a wave to shore. Sometimes Agatha took a painful nose dive in the sand, but soon she got the hang of it.

Surf Bathing at Muizenberg ca. 1929

Fish Hoek on False Bay was the place to get in a good swim. Many days, though, Agatha had to settle for bathing closer to their hotel in an outdoor seawater pool at Sea Point, on the Atlantic coast, where Agatha felt like a fish in an aquarium.

Agatha swims at Sea Point, February 1922. Photo from the Christie Archive

In late February 1922, she and Archie were luncheon guests at Admiralty House in Simonstown on False Bay. Their hosts Admiral Sir William Goodenough and Lady Goodenough took them down to the pier to show them where they bathe. Agatha recalled:

“…and Lady G. looking down into the water said quietly: ‘Ah, I see the Octopus has gone. Such a fine fellow – about 5 ft. across.’

We bathed from the other side of the pier. I never care to bathe close to an octopus!”

Agatha wasn’t aware at the time, but there were far more dangerous animals lurking in the waters of False Bay than an octopus. Out in the middle of the bay was Seal Island, the home of the Cape fur seal, the favorite food of the Great White Shark. The Great White Shark is one of the most notorious and ferocious hunters on earth. False Bay has the highest number of Great White Sharks in the world. (2)

Agatha wasn’t aware at the time, but there were far more dangerous animals lurking in the waters of False Bay than an octopus. Out in the middle of the bay was Seal Island, the home of the Cape fur seal, the favorite food of the Great White Shark. The Great White Shark is one of the most notorious and ferocious hunters on earth. False Bay has the highest number of Great White Sharks in the world. (2)

Two months passed. On May 6, 1922, Agatha and the B.E.E. mission folks were on the distant and strange Australian island of Tasmania. In her official capacity as Mrs. Christie, she passed that Saturday on dry land, without incident, creating local bonhomie by visiting a museum, attending the races, and playing bridge.

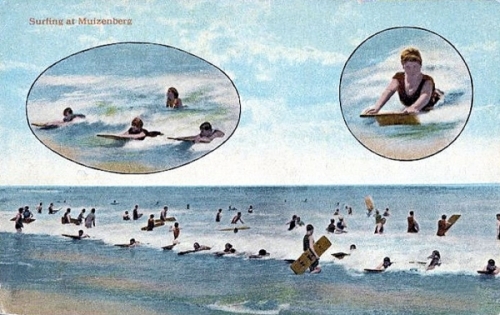

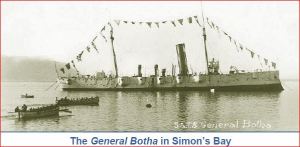

Meanwhile, back in Simonstown, South Africa, where her friends Admiral and Lady Goodenough lived, the ones with the octopus below their pier, where Agatha swam, a more terrible scene was being played out. That morning, a student from the University of Cape Town named Edward Pells decided to go for a swim in Simon’s Bay (off False Bay). The water was calm, translucent. The General Botha was moored in the harbor 300 meters off the end of the jetty and Pells decided to slowly swim around the training ship. He dove in. He was halfway to the ship when there was a swirl of water below him, followed by “what felt like the impact of a torpedo. Simultaneously he was seized by very powerful jaws…” The shark turned downwards into the depths, taking Pells with him. Pells pushed against the shark’s body, tearing himself free, but not before his stomach, thigh, and back were gashed and shredded by the shark’s teeth. He lunged fifteen feet to the surface of the water, the shark close by. He gasped for air.

The General Botha was moored in the harbor 300 meters off the end of the jetty and Pells decided to slowly swim around the training ship. He dove in. He was halfway to the ship when there was a swirl of water below him, followed by “what felt like the impact of a torpedo. Simultaneously he was seized by very powerful jaws…” The shark turned downwards into the depths, taking Pells with him. Pells pushed against the shark’s body, tearing himself free, but not before his stomach, thigh, and back were gashed and shredded by the shark’s teeth. He lunged fifteen feet to the surface of the water, the shark close by. He gasped for air.

Fortunately three Malay fishermen in a pram had witnessed the attack and made fast to his rescue. Pells could not speak, he could not call for help; he was in shock. They hauled Pells over the gunwale as the huge shark surfaced and bumped their boat, threatening to overturn it and them into the blood-tinged water.

Once to shore, Pells was rushed to the hospital where his blood was staunched and his wounds were stitched.

Meanwhile, the shark was still cruising the bay. Two days would pass before a local fisherman would harpoon and kill it in a “battle royal,” then hang it by its tail from an old gum tree for all to witness. The shark was over 12 feet long (3.66 meters) and weighed over a thousand pounds (+453.6 kilograms). It was a Blue Pointer (Carcharodon carcharias) known as the Great White Shark. (3)

Meanwhile, the shark was still cruising the bay. Two days would pass before a local fisherman would harpoon and kill it in a “battle royal,” then hang it by its tail from an old gum tree for all to witness. The shark was over 12 feet long (3.66 meters) and weighed over a thousand pounds (+453.6 kilograms). It was a Blue Pointer (Carcharodon carcharias) known as the Great White Shark. (3)

In her autobiography and letters, Agatha Christie mentions her disappointment that, in some places along the South African coast, “one had to bathe in an enclosure, netted off from the open sea.” There was a reason for that. Those outdoor swimming pools protected the swimmers from being eaten by sharks. From 1905 to 2013, there were 239 unprovoked shark attacks in South African waters and 53 were fatal. Compare those figures to the ones for the United Kingdom, Agatha’s home country. From 1847-2013, there were only two shark attacks, and neither were fatal.

The admiral and other South African government officials should have advised Agatha and her friends of the dangers of swimming in False Bay. Coming from England, they would not have dreamed of sharks being in the water.

Fortunately, when they were in Fiji later that August, they were forbidden to swim in the Pacific because of the danger of shark attack.

(1) Christie, Agatha. Agatha Christie: An Autobiography. New York: a Berkley book from G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1977

(2)

(3)

Additional source: Christie, Agatha. The Grand Tour: Around the World with the Queen of Mystery. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2012.

For more on Agatha Christie, click here.

Read Full Post »