In the early morning hours of August 6, 1922, crime novelist Agatha Christie and her husband, Archie Christie, sailed into Honolulu, Hawaii, on the Makura and hailed a taxi.

On their drive to the Moana Hotel, they passed between palm trees and hedges of hibiscus, red, pink, and white oleanders, and blue plumbago. At their hotel, the sea washed right up to the courtyard steps on Waikiki Beach.

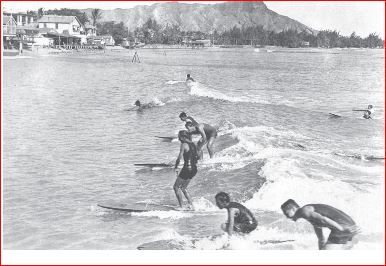

They checked into their rooms. From their window, they saw surfers catching waves to shore. They hurriedly changed into their swimsuits to rush down, hire surfboards, and plunge into the sea.

They had been looking forward to that moment since leaving England eight months earlier. In the interim, the Christies had traveled three-quarters around the world as part of a government trade mission to drum up interest in the 1924 British Empire Exhibition. Their travels had taken them from England to South Africa (where they were introduced to surfing), Australia, and New Zealand. They now had a month-long holiday in Hawaii – all to themselves – before they would rejoin the mission in Canada.

They had been looking forward to that moment since leaving England eight months earlier. In the interim, the Christies had traveled three-quarters around the world as part of a government trade mission to drum up interest in the 1924 British Empire Exhibition. Their travels had taken them from England to South Africa (where they were introduced to surfing), Australia, and New Zealand. They now had a month-long holiday in Hawaii – all to themselves – before they would rejoin the mission in Canada.

Surfing was much different in Hawaii than it had been in South Africa. The most obvious difference was the surfboard. In South Africa, the boards were short, curved, and made of light and thin wood.

Agatha Christie and a young naval attaché named Ashby stand on Muizenberg Beach, South Africa, following surf bathing, Jan.-March 1922. Photograph from the Christie Archive

In Hawaii, however, they were great slabs of wood, ridiculously long and even more ridiculously heavy, made even heavier by the fact that, to find a decent wave to catch, a person had to paddle the board a long, long way out from shore to a reef where the waves broke.

In South Africa, the waves broke close to shore and were gentle.

Then there was the matter of what to do when you caught the right wave. In South Africa, surfers rode the wave on their stomachs. In Hawaii, they rode it standing up.

Spotting the right wave to catch was tricky. Agatha recalls:

First you have to recognize the proper wave when it comes, and, secondly, even more important, you have to know the wrong wave when it comes, because if that catches you and forces you down to the bottom, heaven help you….”

On that first day, Agatha indeed caught “the wrong wave.” She and her board were separated and she was forced far underwater. She swallowed “quarts of salt water” and arrived on the surface gasping for breath. A young American retrieved her board for her, saying:

‘Say, sister, if I were you, I wouldn’t come out surfing today. You take a nasty chance if you do. You take this board and get right into shore now.'”

She took his advice and, in time, Archie joined her. They were bruised, scratched, exhausted, but not defeated. Agatha was determined to become expert at surfing.

The second time she went in the water, the waves tore her long, silk bathing dress off her body. She covered herself and went into the hotel gift shop where she bought a “wonderful, skimpy, emerald green wool bathing dress, which was the joy of my life, and in which I thought I looked remarkably well. Archie thought I did, too.”

Agatha Christie, sunburned and relaxed. Waikiki Beach, Honolulu, Aug./Sept. 1922. Photograph from the Christie Archive

In a few days, they moved to a more economical chalet across the road. They spent all their time on the beach or in town drinking ice cream sodas and buying medicines for sunburn. They learned to wear shirts on the beach as their backs were covered with blisters from sunburn.

Their feet were cut to ribbons from the coral so they bought leather boots to wear in the water.

After ten days, Agatha’s skills on a surfboard were improving. After

starting my run, I would hoist myself carefully to my knees on the board, and then endeavor to stand up. The first six times, I came to grief….[but] Oh, the moment of complete triumph on the day that I kept my balance and came right into shore standing upright on my board!”

Because of such vigorous paddling, Agatha developed a strain in her left arm. The pain was excrutiating and would wake her in the early morning hours. Nevertheless, Agatha continued to surf because there was

Nothing like it. Nothing like that rushing through the water at what seems to you a speed of about two hundred miles an hour….until you arrived, gently slowing down, on the beach, and foundered among the soft, flowing waves.”

Researcher Peter Robinson from the Museum of British Surfing says that Agatha Christie is probably one of the first British “stand-up surfers,” along with Edward, the Prince of Wales, who also surfed in Waikiki in 1920 and went on to become King Edward VIII of England for a year. Not to be outdone, let me remind my readers that Agatha Christie is literary royalty, being revered as the Queen of Crime. In 1971, she was made a Dame of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II at Buckingham Palace.

For more on Agatha Christie, click here.

Source: Christie, Agatha. The Grand Tour: Around the World with the Queen of Mystery. United Kingdom: HarperCollins Publishers, 2012