This is the story of how A.A. Milne came to write the stories of Winnie-the-Pooh, or just plain Winnie the Pooh, as Disney would have it.

This is the story of how A.A. Milne came to write the stories of Winnie-the-Pooh, or just plain Winnie the Pooh, as Disney would have it.

It was the beginning of World War I. A Canadian lieutenant, Harry Colebourn, a veterinarian in Winnipeg, offered his services to his country. He was already a trained officer attached to the 34th Regiment of Cavalry, and received orders to leave with the regiment on a train for Valcartier, Quebec, and then take a ship to England. While en route to Valcartier, he was detached from the 34th Regiment and transferred to the Canadian Army Veterinary Corps.

On August 24, 1914, the train stopped at White River, Ontario, an important stop for all trains. Here they would take on coal and water as well as clean out the cinders. The trains carried men and horses, as horses were vital in the war effort. During the four-to-six hour stop, the horses would get off the train to be watered and exercised. Troops would drill along Winnipeg Street where the train station was located.

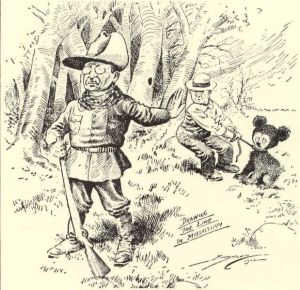

It was on the train platform that Lieutenant Colebourn noticed a man with a female black bear cub on a leash. It was not an uncommon sight for the times; several people had pet bears back then. Many old photos show bears leashed and posing with family members. Lieutenant Colebourn talked to the man and found out he was a trapper. The trapper told the lieutenant that he had killed the cub’s mother. The lieutenant, being a vet, knew that the cub had little chance now of surviving in the wild without its mother. So he paid the trapper $20 for the cub and took it back with him to the train. He named his new companion, “Winnie,” after his hometown of Winnipeg.

From Gaspe Bay, he and Winnie embarked for England aboard the S.S. Manitou with the rest of the troops, where they headed to a military encampment in Southern England on the Salisbury Plain (home to Stonehenge).

Lt. Harry Colebourn and Winnie.

Winnie became the mascot of the C.A.V.C. while the company remained in England. She became a pet to many of the soldiers, following them around like a tame dog. She slept under Harry’s cot in his tent. Sometimes she would climb the center pole of the tent in the night and give it a shake. But, as Winnie grew older and bigger, the men began to worry that the shaking would make the tent collapse in the night with them in it. From then on, they slept with Winnie tethered to a pole outside the tent.

But it was wartime. Soon the brigade was ordered to France. Harry, now a captain, could not take Winnie with him to the battlefront. On December the ninth of that same fall, Harry took Winnie to the London Zoo. It was his full intention to return for her after the war and return with her to Canada. Harry was very faithful to Winnie. When on leave from war duty, he made trips to London to visit Winnie in the zoo.

Winnie continued to capture the hearts of all those who met her. She became a very popular attraction at the London Zoo. It was said that people would knock on her cage door and she would open it and come out. She would allow children to ride on her back and she would eat from their hands. Her attendants considered her trustworthy. No other bears were allowed such contact with the visitors to the zoo.

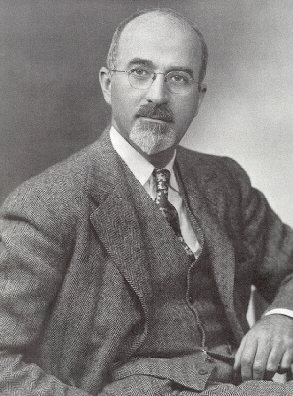

The war ended in 1918 but Harry didn’t take Winnie out of the London Zoo. Instead he donated her as a gesture of appreciation to the zoo for caring for Winnie through the war years and he returned to Winnipeg alone. Living in London at that time was author A.A. Milne.

- Christopher Robin Milne and Winnie at the London Zoo c. 1924

On August 21, 1921, Milne’s son, Christopher Robin, or “Billy Moon,” as he later referred to himself, had his first birthday. Milne gave him an Alpha Farnell stuffed teddy bear which came to be known as “Edward.” From 1924 on, Milne and his son began to visit Winnie the bear in the London Zoo. Christopher Robin became very attached to Winnie. He was even allowed inside the cage to feed Winnie condensed milk. Soon Christopher Robin’s stuffed bear underwent a name change. Although a boy, “Edward” soon became known as Winnie.

Inspired by both the zoo bear Winnie and his son’s stuffed bear of the same name, author Milne began to write and publish his Pooh’s Classics. In 1926 the first and best know of the series called Winnie-the-Pooh, was published, the additional name “Pooh,” being borrowed from the name of a swan. Milne’s characters are mostly inspired by Christopher Robin’s stuffed animals, among them Piglet, Tigger, and Eeyore. These toys are now on display at the New York Public Library.

At first, Christopher Robin enjoyed the fame his father’s books brought him, but, as he grew older, he became resentful. He felt his father was exploiting his childhood for personal gain.

Read Full Post »

This is the story of how A.A. Milne came to write the stories of Winnie-the-Pooh, or just plain Winnie the Pooh, as Disney would have it.

This is the story of how A.A. Milne came to write the stories of Winnie-the-Pooh, or just plain Winnie the Pooh, as Disney would have it.

In Nellie Bly’s book, Ten Days in a Mad-House (see category, “Nellie Bly,” for related posts), Nellie Bly described various women she met in the Blackwell Island Women’s Lunatic Asylum. She was confined to Hall 6 with 45 of the least dangerous women in the institution. While some of them were certifiably “crazy,” (her words), many, she felt, had been wrongly locked up. A Frenchwoman, for example, named Josephine Despreau, fell sick in a boarding house and the woman of the house called in the police. They arrested her and took her to the station-house. She didn’t understand the proceedings because of the language barrier and the judge paid no attention to her protests. She was locked up in the insane asylum in no time.

In Nellie Bly’s book, Ten Days in a Mad-House (see category, “Nellie Bly,” for related posts), Nellie Bly described various women she met in the Blackwell Island Women’s Lunatic Asylum. She was confined to Hall 6 with 45 of the least dangerous women in the institution. While some of them were certifiably “crazy,” (her words), many, she felt, had been wrongly locked up. A Frenchwoman, for example, named Josephine Despreau, fell sick in a boarding house and the woman of the house called in the police. They arrested her and took her to the station-house. She didn’t understand the proceedings because of the language barrier and the judge paid no attention to her protests. She was locked up in the insane asylum in no time.

ellie Bly was put on the island boat and sent to Blackwell’s Island. For ten days, she experienced firsthand the horrors of being locked up in cruel and inhumane conditions. Upon her arrival, she was fed a disgusting meal of pink watery tea, prunes, and bread that was dirty and black and mostly dried dough. She found a spider in the slice given her. She didn’t eat it. Later she learned that the nurses didn’t like it when you didn’t eat your food. They might beat you for that.

ellie Bly was put on the island boat and sent to Blackwell’s Island. For ten days, she experienced firsthand the horrors of being locked up in cruel and inhumane conditions. Upon her arrival, she was fed a disgusting meal of pink watery tea, prunes, and bread that was dirty and black and mostly dried dough. She found a spider in the slice given her. She didn’t eat it. Later she learned that the nurses didn’t like it when you didn’t eat your food. They might beat you for that.

One day, during my stay in New York, I paid a visit to the different public institutions on Long Island, or Rhode Island: I forget which. One of them is a Lunatic Asylum. The building is handsome; and is remarkable for a spacious and elegant staircase. The whole structure is not yet finished, but it is already one of considerable size and extent, and is capable of accommodating a very large number of patients.

One day, during my stay in New York, I paid a visit to the different public institutions on Long Island, or Rhode Island: I forget which. One of them is a Lunatic Asylum. The building is handsome; and is remarkable for a spacious and elegant staircase. The whole structure is not yet finished, but it is already one of considerable size and extent, and is capable of accommodating a very large number of patients.

“So I flew to the mirror and examined my face,” she wrote later. “I remembered all I had read of the doings of crazy people, how first of all they have staring eyes, and so I opened mine as wide as possible and stared unblinkingly at my own reflection.” She began to sweat nervously, which unfortunately took the curl out of her Victorian bangs. Over and over again, she practiced her crazy face in the mirror. She ended up staying up all night, rehearsing her new role, thinking about her new mission, and reading scores of ghost stories to put her in a lunatic frame of mind.

“So I flew to the mirror and examined my face,” she wrote later. “I remembered all I had read of the doings of crazy people, how first of all they have staring eyes, and so I opened mine as wide as possible and stared unblinkingly at my own reflection.” She began to sweat nervously, which unfortunately took the curl out of her Victorian bangs. Over and over again, she practiced her crazy face in the mirror. She ended up staying up all night, rehearsing her new role, thinking about her new mission, and reading scores of ghost stories to put her in a lunatic frame of mind. It had been four months since she’d left Pittsburgh for New York yet Elizabeth Jane Cochran, or “Nellie Bly,” as her byline read, still hadn’t landed a job as a newspaper reporter. She had left the Pittsburgh Dispatch because she was tired of being assigned to the ladies’ pages – writing the society column, reviewing operas, and reporting on the latest women’s fashions.

It had been four months since she’d left Pittsburgh for New York yet Elizabeth Jane Cochran, or “Nellie Bly,” as her byline read, still hadn’t landed a job as a newspaper reporter. She had left the Pittsburgh Dispatch because she was tired of being assigned to the ladies’ pages – writing the society column, reviewing operas, and reporting on the latest women’s fashions.