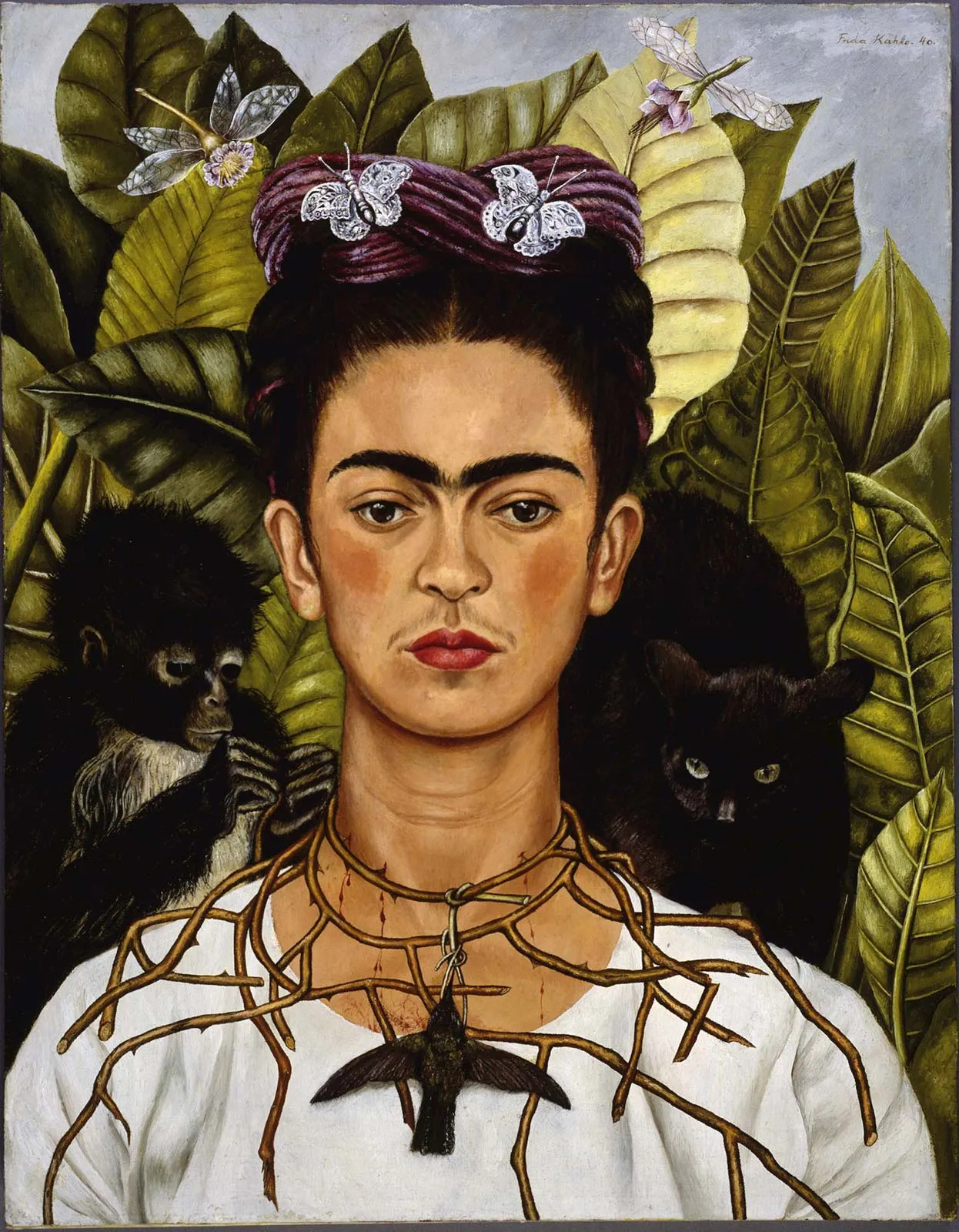

Mary Mallon (1869-1938) was nicknamed "Typhoid Mary," and gained notoriety as history's most famous super-spreader of disease. ("Typhoid Mary," Lisa's History Room)

Yes, there really was a Typhoid Mary. She was Mary Mallon (1869-1938) an Irish immigrant who cooked for wealthy New York families. She is history’s most famous super-spreader of disease.

Mary Mallon was first caught in 1906 when a sanitary engineer was hired to investigate a typhoid outbreak at Oyster Bay, Long Island. Six members of banker Charles Henry Warren’s household had fallen dangerously ill. Warren hired George Soper to discover the source of the contamination before the highly-contagious and deadly disease spread across the privileged enclave of Oyster Bay. (1) Oyster Bay was the site of Sagamore Hill, known as “the Summer White House” of President Theodore Roosevelt from 1902-1908.

George Soper took his assignment very seriously. He first checked the household plumbing. He put dye in the toilet to see if it contaminated the drinking water. It didn’t. He checked the local shellfish to see if the bay was polluted with sewage. It wasn’t. He examined the milk supply in case it was contaminated. It, too, was free of bacteria. (2)

Next, he interviewed the staff. He found that the family had changed cooks on August 4th, when Warren had hired Mary Mallon. Shortly after Mary began as cook, Soper was informed, she had served the household a favorite dessert for Sunday dinner: ice cream topped with freshly-cut peaches.

"Typhoid Mary" Mallon served homemade ice cream and freshly-cut peaches to the Warren household. ("Typhoid Mary," Lisa's History Room)

On August 27, Warren’s daughter, Margaret, fell ill with typhoid fever. Next, Mrs. Warren and two maids became ill, followed by the gardener and another of the Warrens’ daughters.

Knowing that typhoid typically goes from exposure to outbreak in three weeks’ time, Soper had Clue #1: The epidemic had begun with the arrival of the new cook. If his suspicion was correct, Mary Mallon was a carrier who had passed on the disease when preparing the peaches with unscrubbed hands.

Unfortunately, when Soper made this astonishing discovery, Mary no longer worked at the Warrens’. Undeterred, Soper set out to find her. Checking with her employment agency, Soper discovered a second and even more astounding truth: Typhoid had struck seven of the last eight families Mary had worked for. Mary Mallon was spreading typhoid in her path – and she had to be stopped.

But, first, Soper had to prove scientifically that Mallon was a carrier.

This 1883 Puck drawing shows the New York City Board of Health wielding a bottle of the disinfectant, carbolic acid, in an attempt to keep cholera at bay. Immigrants poured into New York City at the turn of the Twentieth Century. Crowded into unsanitary slums, disease ran rampant. By 1890, the era of bacteriology had arrived and scientists understood that diseases like typhoid and cholera arose from germs. Efforts were made to not just clean up the cities but isolate the disease carriers. ("Typhoid Mary," Lisa's History Room)

Mary was difficult to find, but Soper tirelessly tracked her down. Rather overzealously, he

“confronted her in her next employer’s kitchen and asked for blood, urine, and stool samples; she swore she had never been sick and advanced on him with a carving fork. He called in the New York City health department; she threatened its doctor.

Finally, it took five police officers and a chase over backyard fences to subdue her and get her a hospital. High levels of Salmonella typhosa bacilli were found in a stool sample. She was quarantined in a cottage on the Riverside Hospital grounds on an island in the East River.” (1)

Mary Mallon was a medical prisoner. She had been jailed without a trial. Although she was a carrier of typhoid, she was perfectly healthy. She had been shut up in a sanitarium with tubercular patients. She had been treated like a leper.

She sued. People felt sorry for her. Not everyone felt her imprisonment was deserved. In time, she went from Public Menace #1 to a cause célèbre.

Part of the New York American article of June 20, 1909, which first identified Mary Mallon as "Typhoid Mary."

“Eventually, a new health commissioner decided that Mallon could be freed from quarantine if she agreed to no longer work as a cook and to take reasonable steps to prevent transmitting typhoid to others.

Eager to regain her freedom, Mallon accepted these terms. On February 19, 1910, Mallon agreed that she “[was] prepared to change her occupation (that of cook), and w[ould] give assurance by affidavit that she w[ould] upon her release take such hygienic precautions as w[ould] protect those with whom she c[ame] in contact, from infection.”

She therefore was released from quarantine and returned to the mainland.” (3)

But, alas and alack, that’s not the end of the story. For a while after her release, Mary kept her word and worked as a laundress, which paid lower wages than a cook. It was not long afterward, though, that she adopted an assumed name – Mary Brown – and went back to work as a cook.

In 1915, while working as a cook at New York’s Sloane Hospital for Women, she infected 25 people, one of whom died. The typhoid bacteria was traced to a pudding Mary had prepared. She was subsequently arrested and returned to quarantine on the island, where she was confined until her death in 1938.

The cottage on North Brother Island in New York's East River where Mary Mallon, better known as "Typhoid Mary," was quarantined (1907-1910; 1915-1938).

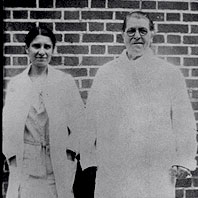

Mary Mallon (wearing glasses) photographed with bacteriologist Emma Sherman on North Brother Island in 1931 or 1932, over 15 years after she had been quarantined there permanently. She worked at the facility and her lab coat was reported to be filthy. (Typhoid Mary: An Urban Historical by Anthony Bourdain)

(1) “The Deadly Trails of Typhoid Mary,” by Donald G. McNeil, Jr. The New York Times, April 14, 2003.

(2) “The Most Dangerous Woman in America,” NOVA, aired Oct. 12, 2004.