Wallis Warfield (Simpson) marries the former King Edward VIII of Britain on June 3, 1937, in France, after he gave up the British throne to be with her. Wallis Warfield Simpson was an American divorcee. For the King to have married her and tried to install her as his Queen would have precipitated a constitutional crisis in Great Britain....The wedding day dawned bright and sunny. It was Wallis' third wedding; her dress was not white but blue. Blue was also the mood. The day before the wedding, the former king's brother, the new British king, George VI, sent Edward a letter granting him and Wallis new titles: the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. The titles were hollow; there was no dominion of Windsor to rule. Even worse: the King's letter contained a bomb - the former king, now titled the Duke, despite his abdication of the throne, could continue to "hold and enjoy...the title, style or attribute of Royal Highness," but his bride, the Duchess, could not, nor could any of their offspring. She, though a duchess, was denied what her sister-in-laws would enjoy - that her name would be preceded by the magic initials 'H.R.H.' At her entrance, no women had to curtsey, no men to bow. She would not be referred to as "Her Highness" but with the lower form of "Her Grace." "What a damnable wedding present!" Windsor shouted upon reading the King's letter. (Bryan III, J. and Murphy, Charles J.V., The Windsor Story. New York: Dell, 1979.)

In 1937, after King Edward VIII had given up the British throne to marry his American divorcee, Wallis Warfield Simpson, the two tiny, trim party animals were exiled to France, where they were doomed to live a life of idle nothingness. They were given the new but hollow titles of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. Accustomed to a lifetime of adulation and privilege yet denied a kingdom, the Duke (and the Duchess), set about creating an imaginary realm of their own that would given them the validation they craved as royals. This new kingdom:

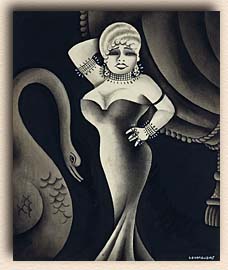

“…was a region whose borders were outlined in society pages, peopled mostly by glamorous nobodies lucky enough to have been born into wealth. It was an ornamental place, whose citizens, according to Andrew Bolton, the curator of ”Blithe Spirit” [a past costume exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum], were unsurpassed ”in the beauty, elegance and craftsmanship” of their dress. For self-indulgence, they were also hard to beat.”

The people who congregated around the Duke and Duchess were dubbed the “Windsor set.” They were all-consumed with the photographic image.

“They arranged those lives to suit the lens. Voluntarily estranged from the real aristocracy, the Duke of Windsor, with the aid of his wife, the former Wallis Warfield Simpson, set up a parallel court composed of people like Elsie de Wolfe, the interior decorator and social arbiter; Mona Bismarck, a gorgeous adventuress who was the daughter of a stableman on a Kentucky horse farm; and Daisy Fellowes, whose fortune derived from sewing machines and who had the distinction of being one of the first people on record to alter her nose surgically.”

the Duke and Duchess of Windsor at home with their precious pug dogs. The Duchess, the former Wallis Warfield Simpson, often appeared in her stylish best in public with a pug tucked under one arm. It became a fashion trend - to carry a dog around with you when away from home.

Granted, the Windsors were despicable people, dining with Adolf Hitler in 1937 and hobnobbing with fellow Nazi sympathizers and British ex-pats Oswald Mosley and wife Diana Mitford. Nevertheless, the Duke and Duchess – and their fancy friends – obsessed with clothing, had tremendous style.

Adolf Hitler kisses the hand of the Duchess of Windsor as her husband the Duke looks on, admiringly. The Duke and Duchess of Windsor visited Germany in 1937 before WWII broke out across Europe. They were outspoken supporters of Nazi fascism and suspected of spying for Germany. At the beginning of the war, the Windsors were whisked out of France to safe haven in the Bahamas, where the Duke served out the war years as governor. There he could do Britain little harm - and he was less likely of being kidnapped by the Germans who were reportedly interested in installing him as a puppet king in a conquered Great Britain under German rule.

Fashion designer Gabrielle "Coco" Chanel (French, 1883-1971) at Lido Beach in 1936

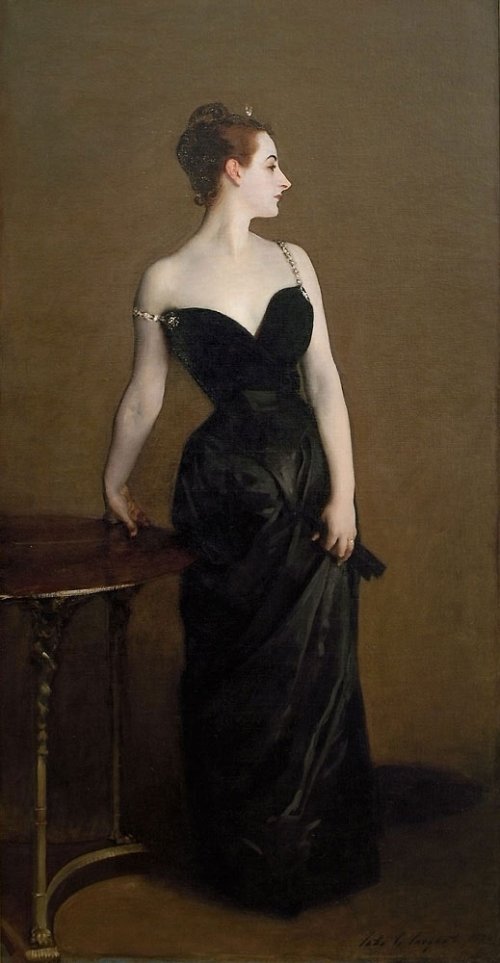

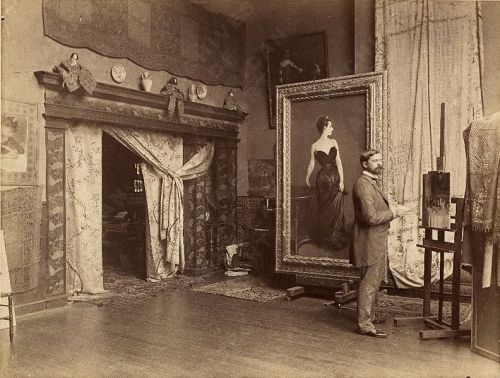

"Evening Dress," 1938. Gabrielle ("Coco") Chanel. Black Silk Net with Polychrome Sequins. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Special Exhibit: "Blithe Spirit: The Windsor Set" The decoration of sequined fireworks on this evening dress, which was worn by the Countess Madeleine de Montgomery to Lady Mendl's seventy-fifth birthday party in 1939, is a fitting climax to le beau monde of the 1930s. It was the end of an era when, on Sept. 1, 1939, Parisians heard an early-morning radio announcement from Herr Hitler in German, at once translated into French, that "as of this moment, we are at war with Poland." The thirties were over; the Second World War had begun.

The Windsors were famous for their elegant Paris dinner parties, creating a demand for expensive clothes and jewels for them and their guests. Thus, the prewar years in France from 1935-1940 were rich in the decorative arts, putting trendy fashion designers front and center. It was a time when Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel was “rethinking the suit” to allow for the way women really move and Elsa Schiaparelli* was designing lobster dresses with surrealist Salvador Dali.*

Then Hitler invaded Poland and World War II shattered the fantasy world of endless cocktail parties and silk and organza gowns made to order. The Germans invaded and occupied France.

Shockingly, Coco Chanel spent the war years living at the Ritz in Paris with a Nazi officer. After the war was over, Chanel was arrested by the free French for suspicion of collaborating with the Nazis. She purportedly offered this explanation for sleeping with the enemy:

“Really, sir, a woman of my age cannot be expected to look at his passport if she has a chance of a lover.”

It is generally believed that Winston Churchill intervened with the French government, convincing them to let his old friend Coco Chanel escape to Switzerland rather than be paraded through the streets of Paris with her head shaved like other female Nazi collaborators.

Women accused of being Nazi collaborators are humiliated after the liberation of France, 1944. © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis

Fast forward 19 years. It's November 22, 1963. Jackie Kennedy,* in her pink Chanel suit and pillbox hat, is riding through Dallas in a motorcade just minutes before a sniper kills her husband, President John F. Kennedy